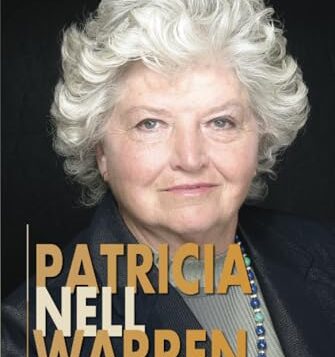

PATRICIA NELL WARREN

PATRICIA NELL WARREN

A Front Runner’s Life and Works

by Nikolai Endres

Peter Lang Publishing. 270 pages, $94.95

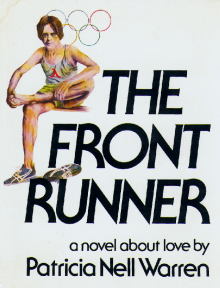

Straddling a line between popular biography and doctoral dissertation, Nikolai Endres’ study of Patricia Nell Warren, author of one of the most popular gay novels of all time, The Front Runner, purports to be the first work to cover her entire life and work. When The Front Runner appeared in 1974, it was in many ways, as its title implies, the first of its kind: a popular novel that presented a gay relationship as “normal” and even healthy. And it was the first gay novel to become a New York Times bestseller.

For an LGBT community just beginning to emerge from its collective closet, the book was nothing short of a revelation, with many millions of fans over the years declaring that the book had saved their lives. Academia has been less kind, often categorizing Warren as a popular or “romance” novelist. Indeed, in 1999 when the Publishing Triangle published its list of the 100 best gay and lesbian novels of all time, selected by a panel of esteemed judges, The Front Runner didn’t even make the list.

Given its legions of fans, it would be a mistake to minimize The Front Runner’s merits and influence, and Endres makes the point that Warren’s prose can be attacked on various grounds; her gift was her ability to bring a taboo topic to a wider audience. In other works, such as The Fancy Dancer and Front Runner sequels, she examined themes such as surrogacy, gay parenting, religious dogma, and Native American issues. An activist to the end of her life, this woman from Deer Lodge, Montana, whose big break was getting a job at Reader’s Digest, became a voice for LGBT equality and an outspoken defender of civil liberties and of a secular vision of human society.

Dale Boyer

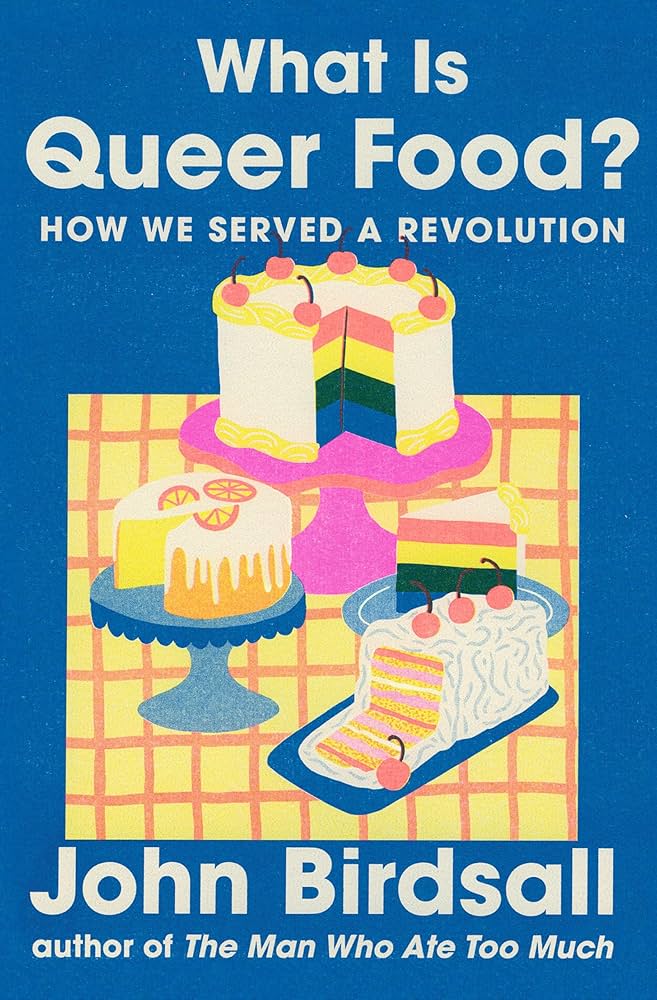

WHAT IS QUEER FOOD?

WHAT IS QUEER FOOD?

How We Served a Revolution

by John Birdsall

W. W. Norton. 304 pages, $29.99

John Birdsall, author of The Man Who Ate Too Much: The Life of James Beard (2020), knows his way around the history of the LGBT food world. In What Is Queer Food? he highlights numerous recipe inventors, restaurateurs, cookbook writers, and food critics, both LGBT people and close allies. Answers to the question posed by the title are wide-ranging and scattered throughout the book, which is arranged chronologically from the late 1800s to the late 1980s. Birdsall has worked hard to be inclusive of many ethnicities and gender identities. One of the lesser-known and most interesting figures is Esther Eng, originally from San Francisco, where she was devoted to Chinese opera. Apparently a butch lesbian, and always a dapper dresser, she moved to New York, where she opened a restaurant in part to assist a Chinese opera company whose members feared returning home after Mao Zedong came to power. She developed a small chain of restaurants, all managed by ex-girlfriends.

Birdsall provides insider information about The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book (1954) and The Gay Cookbook (1965) by Lou Rand Hogan, once a cook on luxury ocean liners. One of the most comprehensive LGBT cookbooks, Out of Our Kitchen Closets, was produced in 1987 by members of San Francisco’s Congregation Sha’ar Zahav. As the cookbook states: “The men made the latkes and the women didn’t.” Birdsall mentions that even mundane recipes become “queer versions” due to cookbook compilers’ intentions. His idiosyncratic writing style may not appeal to all; he often addresses readers in a hectoring second-person voice. Birdsall is on a first-name or nickname basis with all the book’s subjects, from Jimmy (Baldwin) to Alice (Toklas), and that can be off-putting, as can the constant use of the word “queer.” None of that diminishes the well-researched content, but it may lessen the pleasure of reading

Martha E. Stone

RACHEL CARSON AND THE POWER OF QUEER LOVE

RACHEL CARSON AND THE POWER OF QUEER LOVE

by Lida Maxwell

Stanford University Press. 176 pages, $25.

In Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love, Lida Maxwell—a professor of political science and gender studies at Boston University—presents a profound and bold reimagining of Carson’s legacy. By pairing Carson’s pathbreaking environmental work Silent Spring with her lifelong correspondence with Dorothy Freeman, Maxwell makes a compelling case for understanding their relationship as a form of queer love that defies conventional categories of sexuality and intimacy—one that radically shaped Carson’s ecological vision.

Maxwell contends that Carson and Freeman’s shared wonder at the natural world—the call of birds, the turning of seasons, and the quiet communion with the landscape—is a form of multispecies intimacy. These moments become philosophical and political forces when understood as “world-disclosing love”: a mode of connection that reveals new, life-affirming ways of being with each other and the Earth. Maxwell situates Carson and Freeman within a larger queer feminist lineage, one sharing thematic echoes with Natalie Barney and Romaine Brooks, whose 1930 collaboration The One Who Is Legion envisioned a genderless, resistant mode of subjectivity and love.

Seen through this lens, Carson’s emotional life and environmental activism aren’t separate spheres but deeply intertwined practices of care, resistance, and imagination. Maxwell repositions Silent Spring as an ecological alarm and a love letter to the world, like Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, that calls for an environmental politics rooted in pleasure and reciprocity rather than fear and domination. Love becomes a political act: not private or apolitical, but a force with the potential to reshape our relationships with each other, with nature, and with the planet.

This book is a vital contribution to queer intellectual history, critical thinking, and ecological awareness. It deserves a cherished place not only on queer bookshelves alongside Sappho’s poetry but also in the ongoing conversation about how we live—and love—on an endangered planet.

Cassandra Langer

TOO GOOD TO GET MARRIED

The Life and Photographs of Miss Alice Austen

by Bonnie Yochelson

Empire State Editions. 288 pages, $39.95

Bonnie Yochelson, former curator of photographs and prints at the Museum of the City of New York, has written an informative and incisive biography of pioneering photographer Alice Austen. Unlike Ann Novotny’s earlier work, Alice’s World: The Life and Photography of an American Original, 1866–1952 (1976), in which Austen’s lesbian identity was concealed with coded language, Yochelson situates her as a “new woman” who defied conventional gender rules and roles and celebrates Austen’s 55-year relationship with Gertrude Tate.

Austen spent most of her life living in her family’s home, Clear Comfort, on Staten Island, NY. Her wealthy family expected her to live a life reflective of her class: to marry well, have children, and uphold the expectations of her social position. She defied all of this. She played tennis, rode a bicycle, took up photography, and learned how to develop prints. She photographed just about everything. However, the focus of her photography changed in the early 1890s when she began satirizing gender roles. She photographed female friends in drag or in suggestive tableaus that hinted at lesbian tropes. She described these scenes as examples of “the larking life.” She claimed that “she was too good to marry,” rejecting traditional marriage and all that went with it.

Her involvement with photography extended to her exploration of New York’s working-class neighborhoods. She produced a photographic portfolio, Street Types of New York (1895). She worked for Alvah H. Doty photographing the conditions at the Quarantine Stations at Ellis Island. Yochelson has written a much-needed reappraisal of a pioneering artist who lived life on her own terms. Her photographs serve as documents wherein signifiers of the social norms of class, gender, and sexuality are subverted into images of queer resistance.

Irene Javors

DAYS RUNNING: A Novel

DAYS RUNNING: A Novel

by Shawn Stewart Ruff

Dopamine/Semiotext(e). 216 pages, $17.95

Shawn Stewart Ruff continues the story of Cliffy Douglas, the protagonist of his fiction debut Finlater (2008), in his fourth novel Days Running. A precocious Black high school senior in 1971 Cincinnati, Cliffy is “fagbashed” after being seen kissing his boyfriend. Still closeted, Cliffy is afraid to tell his parents or the police the truth about the attack. He also refuses to name his “psycho motherfucker” attacker, Buster, a notorious neighborhood tough who’s related to a drug dealer.

Cliffy’s relationship with his family is also on the rocks. He and his brothers refer to their parents by the initials of their first and middle names: “LACK.” There are pre-school-aged twins, and his religious mother, “the only person I know whose uplifting intentions manage to scold and make me feel down,” is pregnant again. His self-centered, Vietnam-veteran dad is on antipsychotic drugs after a history of PTSD-related family violence. Cliffy doesn’t recognize LACK’s awkward advice as the help and encouragement it is meant to be. His younger brother Corey is hanging out with a group of thug wannabes, while older brother Dudley can’t wait to leave town.

Cliffy is ready to graduate and go to UCLA, though the plans for his long-distance boyfriend Chip to move to California are becoming less certain. In denial about his anger, disassociation, and recurring vivid dreams, Cliffy wants to retaliate against Buster. At Chip’s insistence, the couple goes after Buster with baseball bats, but that doesn’t seem enough. Dudley gives Cliffy a gun the night he leaves to join the military. Unsure about using it, Cliffy nevertheless escalates the situation through harassing phone calls to Buster, wondering: “What kind of person will I be after all this?” Days Running is a fast-moving journey through Cliffy’s pre-graduation months filled with teenage self-pity and angst and the need to grow into a more open and self-confident gay young adult.

Reginald Harris