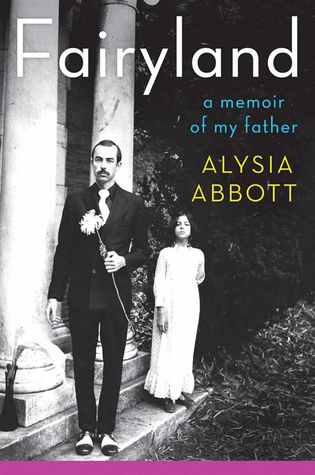

Fairyland: A Memoir of My Father

Fairyland: A Memoir of My Father

by Alysia Abbott

W. W. Norton. 272 pages, $25.95

GAY PARENTING hasn’t received nearly as much attention as same-sex marriage in our recent cultural debates, which makes Alysia Abbott’s Fairyland a book that stands out. Her debut is a memoir about growing up with her single gay father, the late poet Steve Abbott, in San Francisco, during the 1970s and ’80s. After Alysia’s mother died in a car accident while her parents were graduate students in Atlanta, her father relocated with Alysia to San Francisco, the “fairyland” of the book’s title. Her reflections on her relationship with her dad and the city of her youth are both spirited and compelling, and also deeply moving in the final chapters that chronicle her father’s death from AIDS.

Alysia’s unique perspective in the memoir is partly influenced by her father’s candor. He’s often represented by his own writing here, in snippets quoted from his poetry, journals, and correspondence. Raising a child alone at the height of gay liberation in the queer epicenter of 1970s San Francisco was certainly no easy task, making Steve Abbott’s own perspective equally unique. In one letter to a friend, he writes of his daughter: “Faggots find her cute but are afraid of her. Child = responsibility, the ultimate freak-out for the selfish and the escapists.”

From her earliest years, Alysia is made glaringly aware of her family’s difference from the other families around her. In her elementary school math class, when the students are told to draw the “shapes” of their families, she realizes that among the other students’ triangles and rectangles, “Dad and I were just two points. A line. Not even a shape.” She also learns to take delight in the playful queerness of her father and their unusual family unit, until the peer pressure and conformity of her teenage years begin to bear down.

As she grows older, however, Alysia is better able to appreciate in retrospect the political force of her father’s daring decision to raise her alone. “My parents believed in revolution,” she writes, “that the rules of family needed to be shattered and rewritten, that there should be room in society and marriage for sexual curiosity, even transgression.” In her childhood days, she witnessed the progression of her dad’s various boyfriends coming and going through their Haight-Ashbury apartment. She became attached to some of these young men, too, even climbing into bed to find comfort, snuggling beside the two men in the mornings.

Eventually, Alysia comes to understand herself as a member of what’s come to be called the “queerspawn” community, which encompasses all children of GLBT people. While acknowledging the powerful bond that she feels with other offspring of gay parents, she also describes the sense of outsider-dom that ultimately unites them: “As kids, we often existed in a state of uneasiness, a little too gay for the straight world and a little too straight for the gay world. To grow up the child of a gay parent in the seventies and eighties was to live with secrets.”

When her father’s sexual identity begins to manifest itself physically after he’s diagnosed with AIDS, Alysia is forced to “come out” more openly as the child of a gay man. She leaves San Francisco to attend college in New York and Paris, at which point her father’s presence in the book is sustained largely through the handwritten letters that he sent to her regularly, sometimes as many as three per week, throughout their time apart. Upon visiting her in Paris, Steve convinces Alysia to return home to take care of him during the final year of his life, a decision that she struggles with, since it compromises her search to become her own person. “I wasn’t ready to care for you when your mother died. But I did,” her dad says, and that convinces her.

Although the memoir’s poignant epilogue laments how the “heavy warlike losses of the AIDS years were relegated to queer studies classrooms,” Alysia is able to process her own grief by closely researching these losses in writing her book two decades later. The memory of the San Francisco of her youth is revived: “a real place with real people, and I was there.”

________________________________________________________

Jason Roush, author of four books of poetry, teaches at Emerson College and New England Institute of Art.