The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov

The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov

by James Steffen

Wisconsin. 326 pages, $29.95

IT MAY BE serendipitous that James Steffen’s Cinema of Sergei Parajanov, the first ever English-language academic text devoted to the Soviet filmmaker, appears at this particular moment. At a time when our news feeds are exploding with reports of Russian state-sanctioned violence against GLBT people, Steffen’s book (re)introduces us to a powerful, poetic, and queer voice from behind the Iron Curtain. Indeed, Steffen’s monograph reminds us that gay people in Russia have a long history of navigating systems of oppression, which have imbued much of their work. The book, a well deserved homage, is the result of years of research and study not only of Parajanov’s films but also of the Soviet filmmaking system and the larger political and cultural atmosphere of a closed society.

Sergei Parajanov (1924–1990), a Georgian-born Armenian filmmaker, made his beautiful films between 1964 and 1988, working within the highly bureaucratic and censorious machinery of the Soviet Union and its party apparatus. His work confronts the viewer with the overwhelming potency of its pictorial beauty. Dressed in the splendid costumes and imagined customs of southern Ukraine, Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan, influenced by the visual legacy of the European Renaissance, Modernism, Christian Byzantium, and Islam, Parajanov’s films are driven by a quest for beauty. While over the course of his career Parajanov made about eighteen films (features, shorts, and documentaries), he is remembered for four, which profoundly marked his life and cinema itself.

Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors propelled Parajanov into the international arena. The film is a boldly conceived and astonishingly photographed blend of mythology, religious iconography, and pagan magic. The camera never seems to stop but pans and loops to capture emotions at their most raw. At its core it is a story of an impossible love between Andrei and Marichka, but it is also an image of life-loving people enduring the cruelty of their historical conditions. The film eschews ideas of class struggle dictated by Socialist Realism and effectively marks the beginning of the Poetic School. After its success, Parajanov was allowed to make The Color of Pomegranates. Ultimately, the film was shelved after a short run in Georgia. Characterized by an almost completely still camera, the narrative unfolds in a series of remarkable tableaus devoted to the life and death of the Armenian poet Sayat Nova.

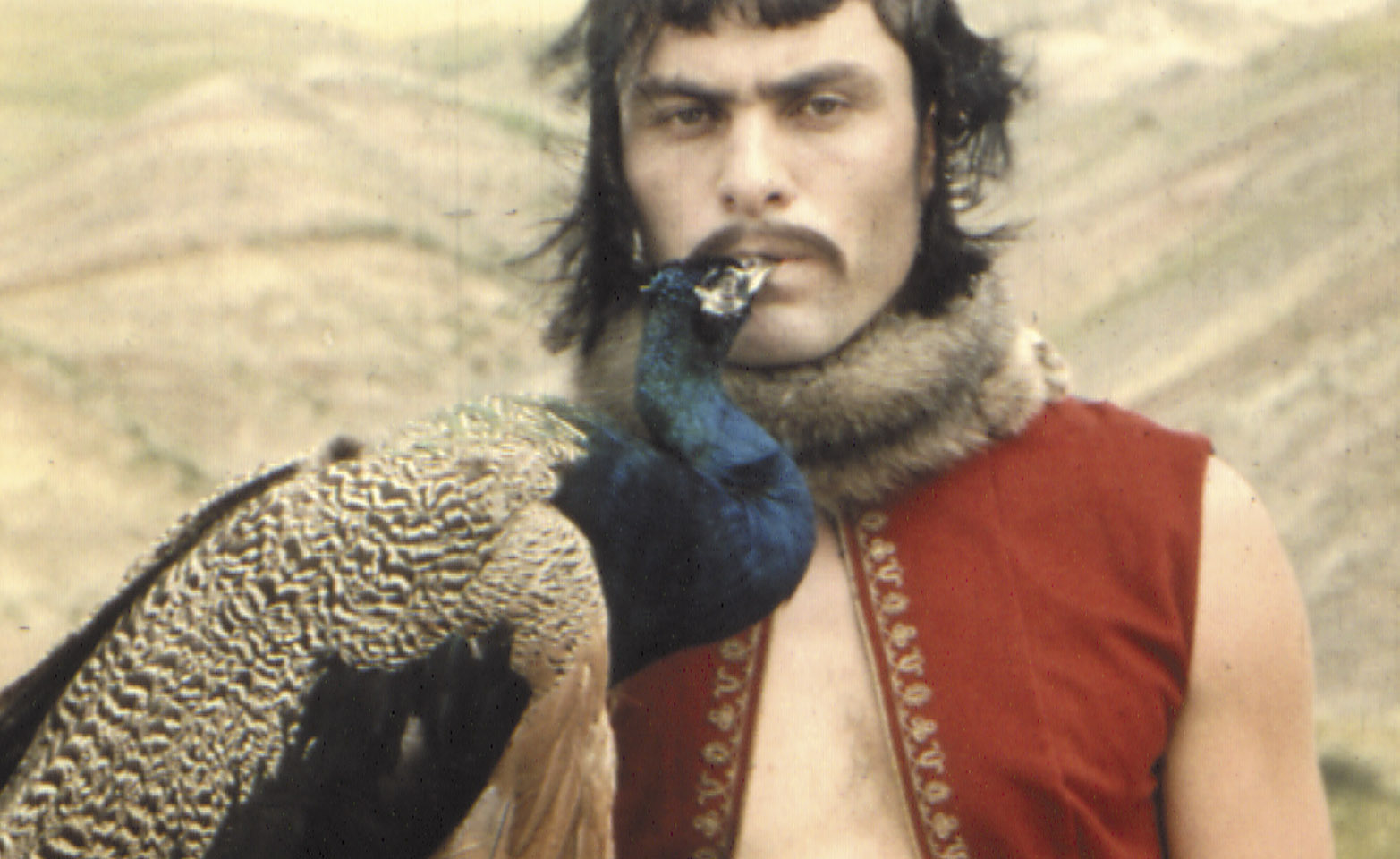

In 1984, after years of incarceration, Parajanov directed The Legend of Suram Fortress. True to his established technique of vivid, surreal visuals, the film is an ode to Georgian warriors told through the story of a crumbling fortress. Here themes of impossible love, prophecy, and martyrdom come together as the screen is filled with images of white horses swathed in pale blue fabrics and tightrope walkers performing in the desert. Parajanov’s last film, Ashik Kerib, was based on an Islamic legend and was visually inspired by Persian miniatures. It follows a traveling minstrel on his journey toward his beloved. It is the most optimistic of his films. Working with the sound editor, Parajanov applies his characteristic collage technique to create a soundscape based on the ballet Gisèle and traditional Azerbaidjani music.

Steffen remarks that “the beauty of an object often becomes the main point of a shot.” Parajanov himself stated that he “may have received this love for authentic texture in films thanks to Pasolini or Fellini,” thereby placing himself in an international filmic tradition. In fact, this obsession with the surface is so strong that Parajanov’s material culture often overwhelms the story itself.

This emphasis on material beauty encompasses people as well, and it is through them that queerness manifests itself in Parajanov’s films. Quite often the object of beauty is the face of his young male protagonist or his muse, actress Sofiko Chiaureli, who figures prominently in all four of his major films. These beautiful figures are generally presented in frontal close-ups and only sometimes in a partial state of undress, given the artistic constraints under which Parajanov operated. Some of his screenplays never made it to the screen, and Steffen takes time to point out the overt sexuality of these unrealized texts.

But it is the celebration of beautiful bodies and faces in the films he did make—King Erekle II, the showering monks or Sofiko Chiaureli as the young poet in Color of Pomegranates, and the traveling minstrel in Ashik Kerib—that adds a queer layer to his films. In a section titled “Parajanov’s Oriental Drag,” Steffen discusses Russian attitudes toward homosexuality as marked by an Orientalist prism. In such a context, Parajanov’s own identity as an “exotic other” allows us to read the shirtless, reclining Ashik Kerib as a subversion of the tradition of the Western Odalisque.

Accused of forcing his young male students to have sexual relationships with him, Parajanov was arrested several times over the course of his life. In later interviews, he rejected these accusations. Steffen believes that Parajanov was bisexual with a preference for men, particularly in the later part of his life, and his homosexuality was “exploited as a weak point” by a regime that was unhappy with his subversive ideas in the context of a burgeoning nationalist movement in the Ukraine of the 1960s and 70s. Parajanov was incarcerated and his first two films—Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors (which made him a popular artist inside and outside the Soviet Union) and Color of Pomegranates (the masterpiece for which he is largely remembered today)—were banned.

As a scholar, Steffen makes great use of the documentation surrounding Parajanov’s work, which includes all sorts of scripts and literary treatments, original texts that served as the basis for his films, official Communist Party letters and memos, and Parajanov’s speeches and interviews. If the book suffers from any deficit, it is from the publisher’s decision not to publish any color plates of the sumptuous images that Parajanov created. Still, Cinema of Sergei Parajanov fills the English-language lacuna on the topic of this extraordinary filmmaker.

Marcin Wisniewski is a writer and curator. In 2012 he curated the first-ever Canadian film exhibition devoted to Sergei Parajanov.