WORKS OF FICTION that feature characters who are historical figures, especially ones that feature a writer whose work we know better than their biography, can sometimes lead readers to a greater appreciation of, and affection for, the fictionalized writer. One thinks of Michael Cunningham’s The Hours, which won the 1999 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, an exquisitely rendered novel that fictionalizes Virginia Woolf and borrows from her style in Mrs. Dalloway. Similarly, Colm Tóibín’s The Master (2004) and The Magician (2021) brilliantly bring Henry James and Thomas Mann to fictionalized life, providing clear links between the lives they lived and the fiction they produced.

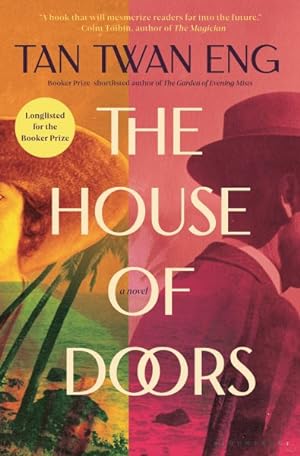

Among these novels that fictionalize a part of another writer’s life, we now have The House of Doors, an elegantly written new novel by celebrated Malaysian novelist Tan Twan Eng. The book draws upon real events to reimagine the details of one of W. Somerset Maugham’s visits to Penang, formerly a state in British Malaya, in the 1920s. In both subject matter and style, Tan’s novel echoes some of Maugham’s life and his own works.

In the novel, the fictional Maugham is near bankruptcy after a disastrous investment failure, and he needs material for a new book to refill his coffers. Dissatisfied with his contentious, expensive wife Syrie Wellcome, he travels (with Gerald in tow) to Penang in search of inspiration. The trip provides him with enough material—unhappy marriages, infidelities, a Chinese revolutionary, and a murder and trial—to inform the six stories in his 1926 collection The Casuarina Tree. Like the stories in that collection, The House of Doors explores themes of race and caste, gender, sexuality, marriage, infidelity, duty, and the crumbling British empire.

In the novel, the fictional Maugham is near bankruptcy after a disastrous investment failure, and he needs material for a new book to refill his coffers. Dissatisfied with his contentious, expensive wife Syrie Wellcome, he travels (with Gerald in tow) to Penang in search of inspiration. The trip provides him with enough material—unhappy marriages, infidelities, a Chinese revolutionary, and a murder and trial—to inform the six stories in his 1926 collection The Casuarina Tree. Like the stories in that collection, The House of Doors explores themes of race and caste, gender, sexuality, marriage, infidelity, duty, and the crumbling British empire.

Maugham has arranged for a two-week stay in Penang with an old friend, Robert Hamlyn, an attorney that Maugham met during World War I, and his wife Lesley (along with Maugham, one of the book’s narrators). Maugham senses that all is not right in the Hamlyns’ marriage, and with a little prodding he convinces her to share her stories. He finds that he’s right about the Hamlyns. Both Robert and Lesley have had affairs—Lesley with Arthur, an associate of the real-life Chinese revolutionary Dr. Sun Yat Sen; Robert with a subordinate in his law office with whom he often traveled. Seeing a plot thickening, Maugham adjures Lesley and other acquaintances to tell more stories about their lives. Once she warms to Maugham and learns to trust him, Lesley provides her story of her affair with Arthur and her discovery of Robert’s affair with another man. She also relays all the salacious details of the murder trial of Ethel Proudlock, another real event of the time. Proudlock was convicted of savagely murdering her own adulterous paramour—an action that all of the coupled characters in the book probably had contemplated at least once—adding yet another infidelity gone wrong to the story.

Throughout his career, Maugham denied being a “prose stylist.” In fact, in his 1926 short story “The Creative Impulse,” he satirized self-conscious stylists whose works aimed to please only the literati: “It was indeed a scandal that so distinguished an author, with an imagination so delicate and a style so exquisite, should remain neglected of the vulgar.” He preferred instead a short, plain, precise style. Summing up the general critical response to Maugham’s fiction, the critic Lee Wilson Dodd wrote: “Mr Maugham knows how to plan a story and carry it through. Competence is the word. His style is without a trace of imaginative beauty.” Perhaps Maugham’s preference for plain-spoken writing stemmed from his success as a playwright. At one point he had four plays mounted on West End stages at the same time. In his plays, he sought to create dialogue that sounded like real, unadorned conversation. A frequent criticism levied against Maugham was that his casual, colloquial speech sometimes devolved into clichés.

In House, Tan skillfully mirrors that competent, lucid style. There are no frilly flights of descriptive prose, no subplots, no psychological probing, no distractions from the rather simple plot: A famous writer travels to an exotic land to collect tales from the natives and writes a collection of six stories that tell those tales. Lesley’s telling of the Proudlock murder trial story unfolds like any straightforward detective story. Thus, in both content and writing style, Tan has paid homage to Maugham as one of the masters of unadorned prose.

Hank Trout has served as editor at a number of publications, most recently as senior editor for A&U: America’s AIDS Magazine.

Discussion1 Comment

Thanks for this review. I am such a fan of Maugham, and I love this inventive approach to his backstory.