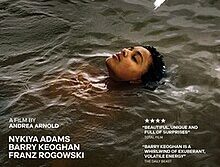

Stranger by the Lake

Directed by Alain Guiraudie

Les Films du Worso, et al.

Blue Is the Warmest Color

Directed by Abdellatif Kechiche

Quat’sous Films, et al.

IT MAY BE a coincidence that two French films with strong gay or lesbian content were featured in this fall’s New York Film Festival just a few months after marriage equality passed into law in France, an event that transpired despite opposition from a vocal minority. If the protests against “Mariage pour tous” demonstrate that a vestige of core conservatism still breathes in France, these films show little of this closed-mindedness.

Stranger by the Lake (L’inconnu du lac), directed by Alain Guiraudie, won the award for best director at Cannes. One distinguishing element of this film is the presence of a few erotic scenes that approach gay pornography. But Stranger by the Lake is a serious, even somber, film about a group of repeat visitors to a gay cruising ground at a pastoral lakeside somewhere in rural France. Told largely from the point of view of Franck, a handsome, fair-haired twenty-something, the story follows his exploration of this sunny, lackadaisical retreat where men of varying shapes and

sizes lie out naked at lake’s edge, then suit up in cutoffs and T-shirts to explore the winding wooded paths near the shore. There, amid quiet broken only by wind through the trees, they perform familiar gay male cruising rituals: silent acknowledgments, firm but mute rejections, exciting encounters with strangers behind bushes or sheltered within tall beach grass. Then there’s the hapless fellow who’s reduced to voyeurism while stroking himself in the hope that someone will take pity. A vague sort of community emerges, where the regulars know each other by sight and attractive newcomers like Franck (in fact, a seasonal returnee) are treated with special interest.

Soon enough, Franck becomes enamored of the swarthy Michel, whose dark mustache marks him as a latter-day 1970s “clone.” Michel swims through water like a shark and responds with lively interest to the preppy Franck, which annoys Michel’s most recent summer conquest. In quick strokes, Guiradie establishes the Franck-Michel pairing as one of l’amour fou, the crazier, we suppose, for their instant willingness to have bareback intercourse.

What makes Franck more interesting than a mere pretty boy savoring easy pickings is his platonic friendship with the lakeside’s resident loner, Henri, a middle-aged man with a hetero past and gay sex on the down low. Henri is an overweight sage, willing to state unadorned truths but suppressing some deep internal misery to which he sometimes gives voice. He appears to be a handsome man gone to seed, who sets himself apart from the regulars, spending his afternoons looking out over the placid waters from a raised perch. He doesn’t swim or lie out in his birthday suit, and he makes no effort to extend himself socially or sexually. He doesn’t go into the woods to cruise. Yet once Franck and Henri have their first friendly exchange, Franck is drawn to the older man for his calm affability and lack of pretense, and Henri is drawn to Franck in gratitude for his easy conversation, his youthful élan, and, no doubt, for the good luck of having a handsome regular pay him any attention at all.

For the first quarter hour, Guiraudie presents a leisurely portrait of gay rites of sociability and sex in provincial France. His camera work and sound editing are distinguished for the beauty of their images and the aptness of the ambient noise: a swimmer cutting through the water; the whisper of leaves as the wind thrashes through them; the racing exhalation of lovers reaching climax. But, soon enough, a complication develops, as we witness from Franck’s vantage the late-night drowning of one of the local habitués by the man’s lover. From then on, the film proceeds on a dark new path concerning Franck’s ethical dilemma: will he tell what he knows? When the body is discovered and a straight police inspector starts nosing around the resort, we wait with growing tension to see if Franck’s silence will break, a silence born of an odd loyalty that might strike some viewers as morally flawed.

Stranger by the Lake is a highly atmospheric and often enigmatic film, a slice of gay life in which a criminal mystery plays out against an indifferent but beautiful landscape, with shades of early Antonioni or even Terrence Malick: L’Avventura, Blow-Up, or The Tree of Life. In classically structured scenes that describe the repetitiveness of a summer’s sex addiction, Guiraudie has fashioned an intensely dark fable for our times. That we might wish for an ending that offers a clearer ethical stance would be to ask a French director to “go Hollywood.” Stranger by the Lake is a fascinating account of passion at the boundary of obsession.

AN EVEN more explicit treatment of same-sex love is presented in Blue is the Warmest Color, Adèle: Chapters 1 & 2 (La vie d’Adèle), by the Tunisian-French director Abdellatif Kechiche. The story covers roughly ten years in the life of a sexually and intellectually awakening teenage girl, Adèle (played by Adèle Exarchopoulos). At a high school in Lille, Adèle is part of a cool crowd of sexually precocious girls who ogle the boys, talk frankly about sex, and egg each other on. She responds to one attractive young man’s hesitant approaches; the two talk briefly about musical and literary tastes and advance rather quickly to bed. But something is not quite right for Adèle.

Soon thereafter, an innocuous private conversation with a girl classmate who admits to finding Adèle attractive results in a tentative series of kisses from which both girls abruptly withdraw. One evening, Adèle goes out with a boy buddy who takes her to a local gay bar, and from there she wanders into the nearby lesbian scene and finds herself in conversation with Emma, a lovely older “butch” with dyed blue hair. They’ve seen each other before on the street, and the street-wise Emma knows she has in Adèle an underage innocent who is not to be rushed. At least not that night.

What follows is the heart of the film, a meditatively languorous examination of two young women from different social classes and with different career aims whose intensely passionate relations, filmed with both candor and grace, allow them to bridge their differences. At home chez Adèle, we come to understand the conventional, working-class background of her parents, while Emma, an art student set on a career as a painter, issues from a more sophisticated milieu. Emma’s mother and stepfather are frankly welcoming of Adèle, this new girlfriend who hopes to be a teacher of young children. Meanwhile, Adèle’s less worldly parents, meeting Emma for the first time, are led to believe that the girl with blue hair is just another friend of their daughter.

The camera adores the natural beauty of the girls’ lithe, nubile bodies. The intensity of the lovemaking scenes, like the unforced conversations between the pair, achieves a kind of cinematic verisimilitude that’s rare on film. Their dialogue sounds spontaneous and their sexual intimacies appear unrehearsed. We might assume that director Kechiche, a straight man, enjoyed just a bit too much the prerogatives of the male gaze. But the script is also an inquiry into the subtle power differences between two women of disparate temperaments: Adèle, socially awkward and less assured; and Emma, brazen and professionally focused. This makes the erotic scenes seem a necessary examination of how these imbalances are redressed.

Of course, in drama there must be conflict, and (spoiler alert) the course of this love story does not run smoothly. For all Emma’s romantic assertions about being an artist uncompromised by commercial considerations, it turns out she’s a quite eager careerist. And while Adèle may seem tentative and awkward in the company of Emma’s crowd, as a teacher of small children she demonstrates warmth and authority, tenderness and command. But Emma has been Adèle’s erotic mentor and takes the lead role in determining the social shape of their relationship. Faced with such an assured mistress, Adèle seeks the occasional company of her teaching colleagues—and this leads to trouble.

Remarkable as it may seem for a nearly three-hour film, Blue is the Warmest Color remains a spellbinding, almost documentary account of one young woman’s coming of age: her first fuck, first true love, first job, first great heartache. Both actresses give complex portrayals of young women in love, first lost in their private dream, then riven by temperamental differences that are bridged and then broken. When the Palme d’Or was awarded at Cannes in spring 2013, it didn’t just go to Kechiche as director but also to his two female stars. Kechiche has done something improbable: a male director has given us an account of lesbian love that is both sexy and sobering, and given space to two young actresses, lovely and natural in their physical beauty, to really give portrayals beneath the skin.

Allen Ellenzweig, a frequent contributor to these pages, is the author of The Homoerotic Photograph.