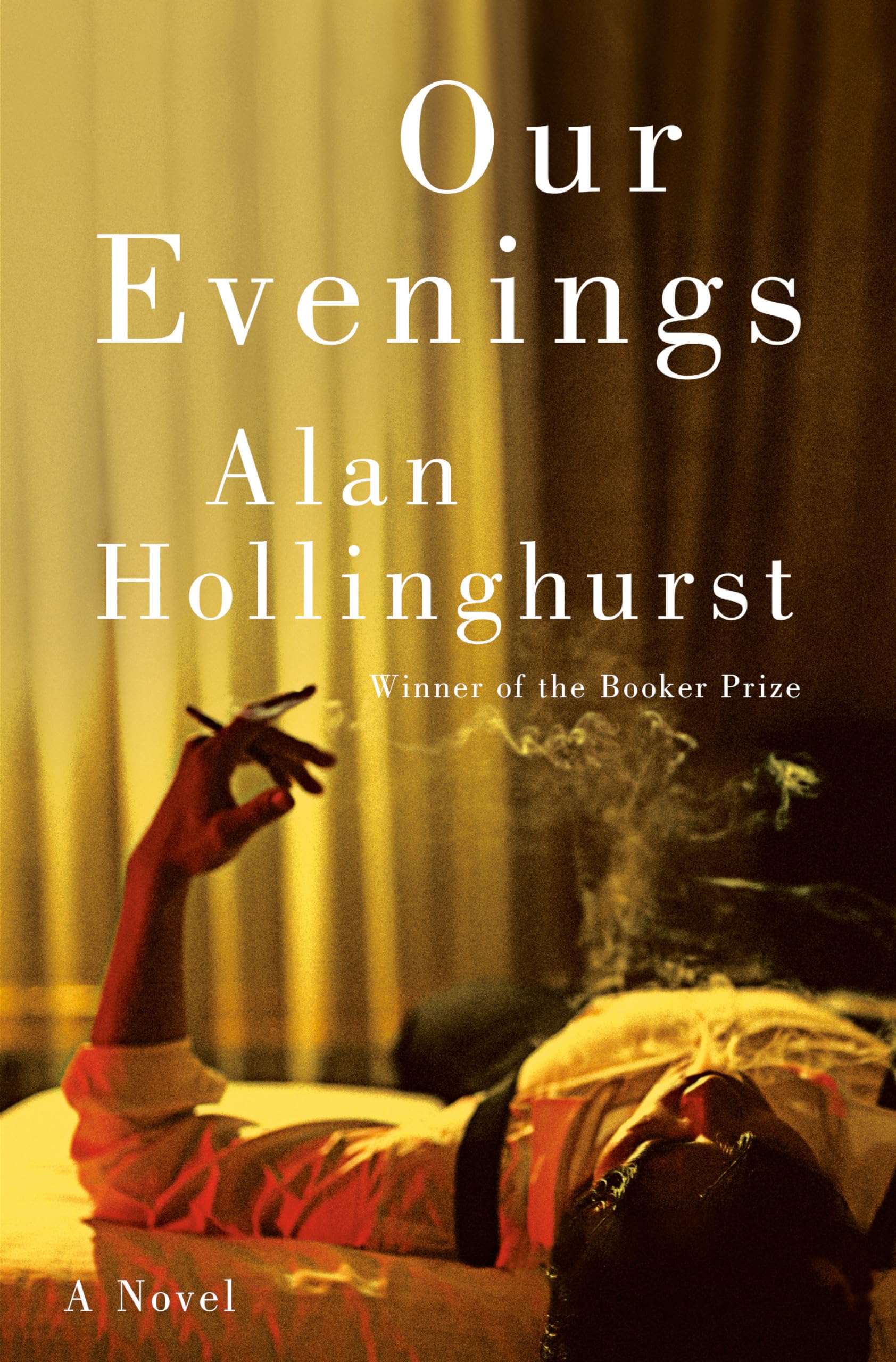

OUR EVENINGS: A Novel

by Alan Hollinghurst

Random House. 487 pages, $30.

“DAVID’S GOT an amazing memory,” says the husband of the narrator of Alan Hollinghurst’s new novel, Our Evenings, and that’s an understatement. Hollinghurst is known for his love of precise description, and David Win, the half-British, half-Burmese actor whose life story we are reading, has the same all-noticing and descriptive eye. In Hollinghurst’s first novel, The Swimming Pool Library, it was architecture that was minutely described. Here, six novels later, it’s absolutely everything that a young man growing up in a provincial English town would notice about his community—especially if he’s biracial and homosexual. (Full disclosure: Alan Hollinghurst reviewed my last novel, The Kingdom of Sand, in The New York Review of Books, 7/28/22.)

Years ago, when readers dazzled by The Swimming Pool Library were waiting to see how Hollinghurst would solve the second novel problem, he produced a follow-up called The Folding Star—an atmospheric prose poem about a Flemish painter that is his only book not set in England. Midway through that novel, the hero goes back to England to visit his parents in the small town in which they live. Reading that brief interlude, I remember sensing that we were being given a tiny bit of autobiography—which made me wonder if he would ever write about that.

Our Evenings is deeply nostalgic, and that is one of its great strengths. It’s by far his most emotional book. The core of the novel is the relationship between mother and son. He is her pride and joy, so excellent a student that he earns a place in a public (i.e., private) school through the philanthropy of an arts patron named David Hadlow, whose own son is Win’s classmate—one of the bullies, in fact, who disdains Win for being what the English used to call “a wog,” with whom he has his way after lights-out in the dorm. No details are provided, but a reference made by Win to his “bloody underwear” implies that anal sex took place.

Our Evenings is deeply nostalgic, and that is one of its great strengths. It’s by far his most emotional book. The core of the novel is the relationship between mother and son. He is her pride and joy, so excellent a student that he earns a place in a public (i.e., private) school through the philanthropy of an arts patron named David Hadlow, whose own son is Win’s classmate—one of the bullies, in fact, who disdains Win for being what the English used to call “a wog,” with whom he has his way after lights-out in the dorm. No details are provided, but a reference made by Win to his “bloody underwear” implies that anal sex took place.

Win has to put up with a lot—not only sexual predation but a nearly ceaseless stream of what are now called micro-aggressions. When he and his mother walk through their little town, they are the subject of snubs by the people they pass. Greetings offered by mother and son are met with averted faces. The mother reminds one of Hester Prynne in The Scarlet Letter, though marked in this case not by the letter “A” but by the color of her son’s skin. They are ostracized even by his mother’s family. And there are so many times when someone on the street tells her son to go back to where he came from that it begins to seem slightly unbelievable—until you remember that many of these incidents are set in the 1950s and ’60s, long before social change made racism unacceptable. But young Dave does not let the malice deter him. He remains a good-natured, intelligent, ambitious, and handsome young man, patient and uncomplaining until, just as he’s about to get his degree at Oxford, he does something that reveals the rage he has been repressing all this time.

And since Hollinghurst is a master of plot, he never lets anything remain as it is for very long. Time is always flowing, though often in jump cuts. The novel is strung along the thread of Win’s schools, from public school to Oxford, and that of his relationship with his bullying classmate, Giles Hadlow. We see the two men running into each other over the years as their careers take them to very different milieus. Win becomes an actor in an itinerant theater troupe, Giles a Tory politician.

There are very few writers left who produce old-fashioned—that is, 19th-century—novels in which an author has made up a story with a plot and multiple characters from different social classes with different manners, as Hollinghurst has done here. Until now, his novels have been essentially satires. The villains are usually the right-wing politicians among whom Giles Hadlow ends up as a minister of the arts, even though his own father says he has “no sense of beauty.” Hadlow is not only pro-Brexit; he’s also deeply bigoted when it comes to race, pandering to the revulsion over immigration that fueled the Brexit campaign in real life.

Brexit was a historic event driven by nativist sentiment. In Our Evenings, it’s David Win’s private life through which we glimpse the subject of racism. Even Win’s acting career, which may seem off subject at first, becomes a picture of what it’s like to traipse around the country to less than full halls because audiences won’t accept your troupe’s multi-racial cast. Making Win an actor is an inspired choice. Is there another art form that expresses so well the dilemma of race, especially when theaters do color-blind casting? Will a white audience ever accept a nonwhite Hamlet without finding it an exercise in political correctness? Early on in the book, David is told by an eminent French actress that, if he does become an actor, he will never get the great parts because of his color. Later, Dave falls for a Jamaican-American actor who experiences, like Dave, just what she predicted—that they would only be given lesser roles because they aren’t white. Win seems to have his successes despite that, but they include cheesy projects like the wonderfully named television show, Hibiscus Hotel.

Nevertheless, despite the strength of the racial theme, Our Evenings is, in its cumulative effect, about something even more affecting: the arc of life itself. It is in the end the story of a man’s life from childhood to marriage to retirement. The pain of first love, the misery of splitting up, the ripening of friendship, and the inevitable losses are what move us most. One review of Our Evenings—which included, as most reviews of a new Hollinghurst novel do, a survey of his career thus far—criticized the author for including the same five or six elements in all his novels (the same charge that Gore Vidal leveled against Tennessee Williams about the characters in his plays). But that doesn’t seem fair. Of course writers have particular subjects that inspire, even enable, them to write. And the fact that Hollinghurst has produced a novel familiar in subject (England) but new in its level of intimacy is something to applaud. From the way Win remembers the makes of automobiles that are no longer manufactured to the TV shows he watched with his mother, Win’s memoir is a love letter to the England in which Hollinghurst apparently grew up.

While often very funny—the chapter on a literary festival at a grand country seat, for instance—this is a novel by a man in his senior years (Hollinghurst is now seventy). Although the final macro-aggression is something of a shock, before that the tender nostalgia, the autumnal quality of Win’s old age, are beautifully conveyed. I can’t think of a higher compliment to a writer than a reader choosing to put a book aside before finishing it because he doesn’t want to leave these characters and their world. But that is exactly what this reader did.

Andrew Holleran’s latest novel is The Kingdom of Sand. His other novels include Grief and The Beauty of Men.