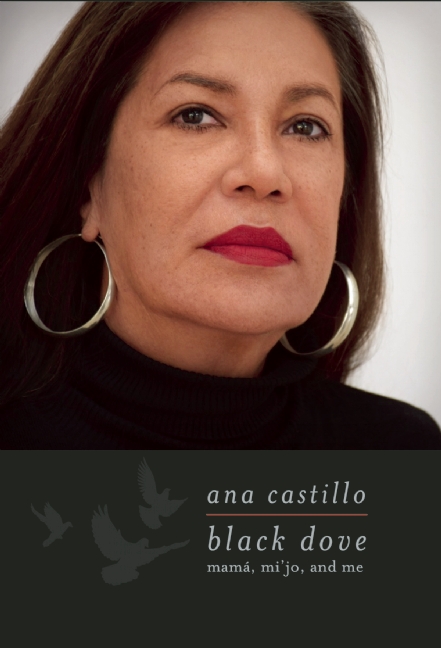

Black Dove: Mamá, Mi’jo, and Me

Black Dove: Mamá, Mi’jo, and Me

by Ana Castillo

Feminist Press. 282 pages, $16.95

IN THIS MEMOIR, Castillo writes about her childhood in Chicago when it was the crucible of the Civil Rights movement, about motherhood and the complications it inspires, and about life as a bisexual Chicana feminist author. Black Dove is stunning in its range of interests and subversive for its linkage of the intimately personal with our current political landscape.

Castillo’s mother was born in the US, forcibly “repatriated” back to Mexico with her family at age nine, then later returned to Chicago to raise her family. Both parents worked long hours, and eventually their daughter felt as much like a satellite at home as she did in school, where black students thought of her as white and white classmates dismissed her for being brown. That dislocation, along with a desire to find a sense of self, propelled her life and work ever after. A depression with episodes of catatonia in her youth foreshadows difficulties to come in the life of her son as he reaches adulthood. Referred to only as “mi’jo,” my son, he is arrested and ultimately spends two years in prison for robbery. When this happens, Castillo describes going though Kübler-Ross’ five stages of grief as she comes to see how depressed (and stoned) he had been for some time leading up to the event. She muses on the disproportionate numbers of black and brown bodies that live behind bars, and on the lack of compassion shown for addicts, especially those who commit crimes, comparing it to attitudes at the onset of the AIDS crisis. “The running sentiment in our heterosexist society was that the disease was punishment from God for sodomy and licentious behavior. Disease doesn’t work that way. And if you believe in God, I think She doesn’t work that way either.” (After serving his time, her son was released and seems to have turned his life around.) An essay titled “On Mothers, Lovers, and Other Rivals” details the fiery fallout from a relationship when the woman with whom she was sharing a home and building a life revealed that she was in love with someone else. “We had been fucking like two starving porn starlets for days and nights” on a brief vacation when it all abruptly fell apart, and the confusion only deepened when the object of her lover’s unrequited desire was described as an “ostensibly straight” and much older woman. Castillo recalls the difficulties of living and working together, of feeling like her ex was both possessive and dismissive of her son as it suited her, and the added difficulties of negotiating all this as two public figures (the woman isn’t named, but is a writer and performer). Decades later, they’ve made peace with each other, albeit via a bumpy and circuitous route. Her ex once wrote and performed in a play about the attraction that trashed their relationship. This piece ends simply: “There are two sides to every story. This is mine.” A constant undercurrent throughout this story is work. At just fifteen years old in 1942, Castillo’s mother had already lost her parents and her Chicago home, so she took a full-time job in a Mexican cardboard box factory (she and her friends would hit the dance hall after work, pleased when the bandleader would dedicate a song to “las cartoneras,” the carton girls). With regard to her own career path, Castillo has been widely quoted as saying: “It was not at all premeditated. I just started writing, and it got out of hand.” Committing to that path has meant moving around the country for teaching gigs and speaking engagements, often with her son in tow when a child, and worrying over bills that included legal fees when he was older. Currently making a life in New Mexico, something of that open landscape infuses this writing to pull the story together across long stretches of place and time. Black Dove is unsparing about the heartache that comes naturally with the passage of time, but it also offers testimony to the power of story as a tool for self-creation.