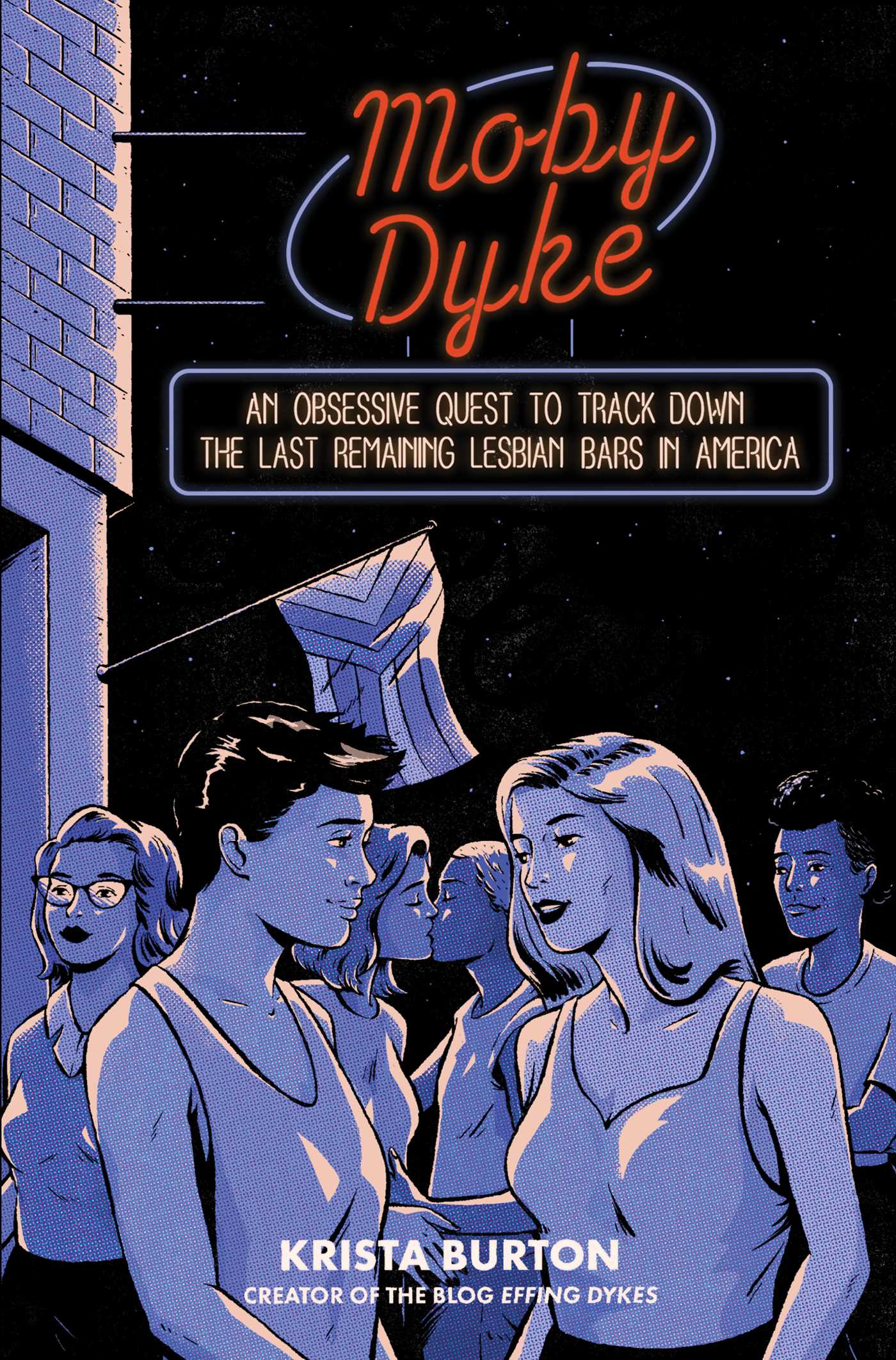

MOBY DYKE

MOBY DYKE

An Obsessive Quest to Track Down the Last

Remaining Lesbian Bars in America

by Krista Burton

Simon & Schuster

383 pages, $28.99

KRISTA BURTON was a self-described “lesbian joke machine” with a blog called Effing Dykes when an editor at Simon & Schuster called to ask if she would like to write a book for them. The editor had just read an article in The New York Times about the dwindling number of lesbian bars in the U.S.—only a couple dozen remain—and Burton had been writing essays on lesbian subjects for the Gray Lady. She leapt at the chance. She was 39, living in a small town in Minnesota, married to a trans man named Davin, working for a company that set up seminars for authors of books about education, and weary of the first year of the pandemic isolation. When, during a FaceTime conversation with friends a year into the lockdown, the question “What did they miss most about life before Covid?” arose, Burton instantly replied: “being in a packed, sweaty dyke bar, surrounded on all sides by queers so close they’re touching me, and then to feel someone with a drink in one hand try to inch past me. You know—when the bar’s so crowded that your arms are up and held tight to your body, with all your elbows tucked in, and you can feel people jostling you from all sides!” And that’s what she set out to find (once the vaccine had been introduced).

There were four rules she made for her project: one, that she only visit self-identified lesbian bars, or bars that had historically been lesbian; two, that she visit them at least twice; three, that she try to contact the bar owners and interview them; and four, that she must approach and speak to at least two strangers in every bar. These rules weren’t as simple to follow as they sound. For instance, she confesses to being shy, and, as she points out more than once, gay people in bars are very good at looking at other gay people, but not at engaging them in conversation. And not only was she shy, she wasn’t a big drinker. Raised in a Mormon household in the Midwest, she writes: “I almost never take shots when I go out, because I cannot handle them. It takes exactly 1.5 normal drinks for me to become the kind of person who says shit like, ‘You have the most invisible pores, your skin is unreal’ to people I don’t know.” Of course, once in the bars she finds herself being asked to drink shots on the slightest pretext.

The owner of Manhattan’s Cubbyhole recalls a woman who became so distraught after an argument that she went into the bathroom and ripped the toilet from the cement, flooding the bar. “Maybe it was the grief from the breakup giving her extra strength. The wildest thing was, she came back the very next night like nothing happened.” The combination of alcohol and human relationships has always been volatile—not to mention the fact that lesbian bars were associated with violence when I moved to New York in the early 1970s; I didn’t know about the woman who ripped the toilet right out of the cement, but I imagined fights around the pool table with broken beer bottles.

There’s another reason for why the generally sober Burton has to summon all her nerve to enter these places: she’s a “high femme,” a lesbian who presents herself as so feminine that she’s afraid the other patrons will think she’s straight. So the minute she gets to the bar, she pulls out a little notebook and writes, which leads people to ask what she’s doing, which lets her into conversations and interviews.

Her obsessive journey begins at the Wild Side West in San Francisco and ends at Frankie’s in Oklahoma City, with eighteen bars in between. Along the way, we learn that lesbian bars’ interiors are always painted a particular shade of red—“specifically Pantone #8a0000, if you need a reference”; that all lesbian bars have twinkling lights and some have patios; that lesbian breakups occur mostly in the spring and fall, when the newly divorced come back to the bar to try again; that a woman can claim a table as her own and allow only the people she wants to sit there; that in every lesbian bar there is always a tall skinny white man lurking around for no discernible reason. And then there’s the fact that most proprietors think that “assimilation” explains the disappearance of women’s bars. After a while, even Burton grows bored with this explanation, though it soon becomes apparent that the real value of Moby Dyke is not the answer to the question “Why have lesbian bars shrunk in number?” It’s Burton’s voice.

At one point she observes that gay male bars have not suffered the collapse that lesbian bars have, but we do not learn why. Nor does she go into the extent to which online hookups have altered lesbian life. What intrigues Burton is to what extent the sheer need for customers, or the desire of most owners to supply a place that anyone can call home, has diluted the lesbianism of these spaces irretrievably. Burton seems to long for the good ole days but understands the problem: “Queers want dedicated spaces where they can go, and have everyone around them be queer. That’s because that shit is fun. And it’s such a relief, not to mention so much safer, for us all to be able to be together. But most of us also want each and every version of queerness to be welcomed in those spaces, and who gets to decide who’s queer and who’s not?” That, in fact, is the underlying subject of this book: the tension between inclusivity and exclusivity. It’s one reason Burton is so sensitive about the way she’s treated in each bar she visits.

She has reason to be sensitive. For one thing, she explores several of the bars with her trans-man husband, and she’s never certain when they walk in whether he will be welcomed or shunned. This is complicated by the fact that Burton is so femme that she worries other women will think she’s part of a straight couple. For another, at 39 she’s middle-aged. She has, for example, a veteran’s hilarious familiarity with the songs that are popular in dyke bars on karaoke night, especially one by the Chicks (formerly the Dixie Chicks) called “Goodbye Earl,” about an abused woman who murders her husband. But she is also aware that the baby dykes in the bars have another playlist altogether. Middle age is the condition that has sent her on this journey, and age remains a factor that the bars do not erase.

Despite all this, except for one night when she cannot summon the moxie to approach one more stranger, the voice of our intrepid heroine remains indomitable. There’s a reason her blog is called Effing Dykes—the f-word is strewn copiously throughout this book in all its permutations. Multiple exclamation points and all caps complete the tone of anarchic rage. Sometimes, at the end of a visit that has not produced much that we haven’t already heard (variations on “We want a place where everyone feels at home”) or a pæan to the patio, Burton will end the chapter with a paragraph summing up what she’s learned: a little homily with a positive conclusion. But that doesn’t last long, and it’s soon overwhelmed by the tide of irritability and sarcasm that make this book so continuously funny that I found myself laughing for no discernible reason at the line “I don’t like jalapeños.” The bar owners may all be alike in their welcoming good will, their sanity, and their desire to create a safe space for others (“I’m really good at de-escalating,” says the owner of Slammer’s in Columbus, Ohio. “I used to work in a women’s prison”), but Burton herself is, to say the least, a live electrical wire through which the collision of generations, and the smallest ironies of American culture, are lit in neon.

After all, she is describing a world in which pronouns, adjectives, and nouns have become an impenetrable wilderness of their own. I stopped writing down the descriptors, but before I quit they included: crust punks, sporties, baby butch, soft butch, queermosexuals, high femme, femme slut, stud/ femme, masc-presenting queer, gay-adjacent, and terfs (Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminists, who want none of the aforementioned). And these are a drop in the bucket. The most frequently used pronoun is “they.” And when “they” have a name that can be both a woman’s or a man’s, there is no way of telling what we are dealing with. This, of course, is the point—a rebellion against the binary, the simplicity of the cisgender woman or man—the sort Edmund White described in States of Desire almost 25 years ago after his tour of the American homosexual. That book was mostly about gay white men. This one is about anything but. In Washington, Burton is not surprised when she learns the lesbian bar A League of Their Own is in the basement of a building that contains, on the top floor, a gay men’s bar called Pitchers that is much more spacious and light-filled than its sister in the basement. “I identify as a dyke,” she tells her husband on a visit to New York, “but my husband is trans, and I’m interested in all queers who are not cis men, so maybe that might make me less a lesbian and more like an…exceptual.” “A what?” says Davin. “An exceptual. It’s a word I made up. I’m attracted to everyone but cis men, get it?”

The cisgender gay man is obsolete. “Queer” is a word I can hardly type, much less warm to—it’s a generational thing—but this repurposed slur has obviously replaced “gay” in the national conversation about homosexuality. When The New Yorker reviewed Andrew Sean Greer’s sequel to his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Less, Alexandra Schwartz began her essay by commiserating with the gay white male novelist whose assimilation has robbed him of any cultural interest. Even the prefix “cis” sounds ugly to my ears. There is something about the double sibilance of the prefix that brings to mind the word “cesspool,” and soon after that, the memory of a friend’s mother who used to tell her little boy, when sent to the bathroom to urinate, to “make cissy.” Yet “cis” merely means, according to Google, “on this side”—as opposed to “trans,” which means “on the other side,” as in transalpine, transmit, transfer, or—bingo!—transition.

Burton deploys the new nomenclature with brio, however, though she never asks: What does this endless splintering of sexual identity mean? And could it be the reason for the dwindling number of lesbian bars? It’s nice to hear the bar owners talk about making everyone feel safe and welcome. Anyone who felt they found paradise in their first bar will understand why Burton’s dedication reads: “For anyone who’s ever walked into a dyke bar and realized they were home.” So, when Burton goes to a bar one night to see a show and a cold, grumpy dyke brushes her off with “There are no performances on Monday night,” these mundane words cut to both Burton’s and the reader’s quick. We feel rebuffed, refused, excluded. And when, a few bars later, a different woman asks her to sit down at her table and introduces her to all her friends, the feeling is the opposite, because she’s been taken in, accepted, befriended.

That little lesson—that we go to gay bars to be taken in—is what lies beneath Burton’s tour of the last lesbian bars in the U.S. She concludes, in Atlanta, that even if we don’t need gay spaces (because they’ve been made obsolete by assimilation or the Internet or whatever), we still want them. Of course, this has to do with age: when young, we go to bars to get laid; when old, simply to be with other LGBT people. For proof, just walk by Annie’s on 17th Street in D.C. at any hour of the day or evening and glance in the window.

By the time Burton reaches My Sister’s Room in Atlanta, she has grown so discouraged by her insecurity as a shy femme that she’s changed the stylish outfits she’s been wearing to a faded black sweatshirt dress, with shoes that make her feet look like baked potatoes, an outfit that reads clearly as “queer,” only to find when she walks into the mostly black bar that she has entered High Femme paradise. You can’t predict what you’ll find, though people are friendlier the further south you go, she discovers. And once she gets to Phoenix, she’s going back to the city in which both of her parents used to live.

In the Acknowledgments, Burton thanks her editor for insisting that she make the book “my own story.” The editor was right. The best parts of Moby Dyke are not the descriptions of bars whose only difference becomes, at a certain point, the splendor of their patios, but rather Burton’s reflections when she returns to places she has been before. She used to put on seminars for educators in Columbus, Ohio; she once lived in Seattle; she grew up in Wisconsin; and, in Phoenix, she stayed with her parents after they retired. It’s on returning to Arizona that we learn about her relationship with her mother and father, at whom she used to shout “I hate you!” when growing up. Moby Dyke is not just the slice of Americana that all road trips provide, nor just a portrait of the splintering of sexual identity in the homosexual community; it’s also glimpses of a writer’s past. Indeed, the sheer specificity of those memories produces its best prose, particularly when the author returns to the state in which she was raised. It’s totally endearing when Davin bursts out: “I love the Midwest!” But it’s Burton who tells us why:

You never know what’s going to resonate with you, really. I spent my teenage years formulating and refining plans to get the hell out of Wisconsin and never come back. And now that I was back, decades later, it was almost a relief to be there. I’d missed it. I really love fancy bullshit in all forms—cocktails featuring edible flowers; entrees I can’t pronounce at restaurants you have to book months in advance; confrontationally minimalist shops that sell ambitiously priced bars of soap, and, like, specially blessed brass incense burners—but I don’t come from anything fancy. I come from a place where the hottest restaurant in town was once the newly built Noodles & Company. A place where the sight of a dripping deer hanging upside down on a hook doesn’t make anybody flinch. I’m from a place where three people sitting on lawn chairs inside a garage in February is a party. And it turns out what makes my homosexual heartbeat faster is sticky floors, queers in hunting sweatshirts, gay bears in wool hats saying “Ope” as they inch past you on their way to the bar, and a dart game that pauses for anyone who needs to pee—twenty, thirty, fifty times in a night.

That’s when Moby Dyke is at its best: when it wears its heart on its sleeve, even while covered in the most sarcastic of thorns.

Andrew Holleran’s latest novel is The Kingdom of Sand (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022).