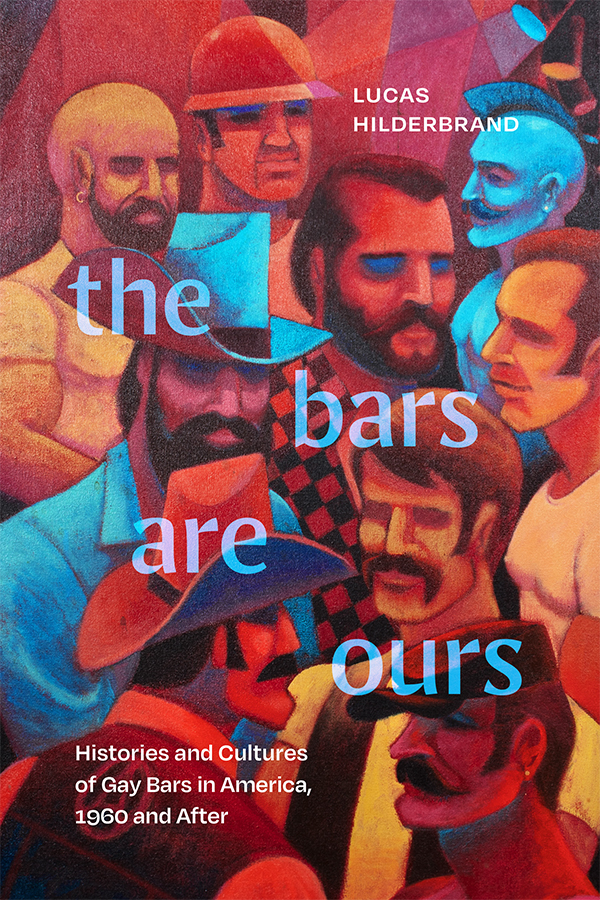

THE BARS ARE OURS

THE BARS ARE OURS

Histories and Cultures of Gay Bars in America, 1960 and After

by Lucas Hilderbrand

Duke University Press. 496 pages, $32.95

IN 2024, it is close to impossible to gauge the influence the bar scene had on queer culture in the U.S. (and elsewhere). Facing a patchwork of homophobic laws and attitudes, gay people, at least those in urban areas, had a place they knew they could go to meet others and congregate: the local gay bar. I’ll never forget stepping into a salty club called Flashback in Edmonton, Alberta (arguably Canada’s most homophobic province), at age sixteen. The sensation was one of both panic and recognition. Somehow, I belonged.

Luckily, Lucas Hilderbrand, a writer of considerable depth and passion, has taken on the task of retelling some of the history and impact of gay bar culture in the U.S. in an illuminating and exhaustively researched tome, The Bars Are Ours. (Full disclosure: Hilderbrand wrote the book on Paris is Burning for the “Queer Film Classics” book series of which I am a co-editor.) Here, Hilderbrand takes us on a fascinating cross-country historical tour of a number of key venues, illustrating how they reflect regional tastes and attitudes and how they influenced the local cultures.

Different bars and regions became notorious for specific scenes. From drag to leather, Hilderbrand takes us into bars and their distinct, loyal followings, including drag bars Mary’s (Houston) and The Jewel Box Lounge (Kansas City) and the leather-infused D.C. Eagle (Washington). His extensive research pays off: in addition to lengthy chapters on specific bars and trends, he also includes “Interludes,” shorter entries on specific aspects of gay life such as the Gay Switchboard in Philadelphia, a help line that provided tips for the curious or support for those longing for connection.

The book also points to two interesting facts about gay bars during their heyday, something not immediately apparent: as straight people began to frequent bars less starting in the 1960s, gay people’s bar habits surged: “The stark divergence in these parallel bar scenes indicates that bars served a different and essential purpose for lgbtq+ people—even if the majority of lgbtq+ people never actually frequented bars.” Hilderbrand also points to the correlation between the rise of gay bars and that of the gay press. So-called “bar rags” were so named due to their reliance on gay bars for advertising and distribution; typically copies were stacked up on counters and free for the taking. The queer press, of course, was vital to building a sense of LGBT identity and community, as well as a political consciousness on a broad range of issues. One cover of an issue of Planet Q is especially chilling, featuring robed KKK members protesting the existence of a gay bar in Somerset County, Pennsylvania. The bars and this unique strain of alternative journalism were inextricably linked.

The book concludes on a less than uplifting note: the waning fortunes of LGBT bars at the present time. Gentrification, online hookup apps, and, ironically enough, the greater mainstream acceptance of queer people have all contributed to this decline. Hilderbrand punctuates the book with a stinging reminder of why the bars were needed in the first place, as he visits the site of the Pulse nightclub massacre, where 49 clubgoers were gunned down in 2016. “Pulse,” he concludes, “was no longer a nightclub but was a symbol of collective pasts and political aspirations.”

The Bars Are Ours is a remarkable achievement and essential reading for any serious student of contemporary queer history.

Matthew Hays is co-editor of the “Queer Film Classics” book series.