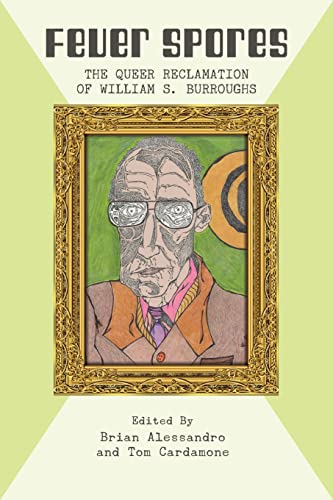

FEVER SPORES

FEVER SPORES

The Queer Reclamation of William S. Burroughs

Edited by Brian Alessandro and Tom Cardamone

Rebel Satori Press

301 pages, $19.95

IN FEVER SPORES, an ecclectic collection of essays and interviews about writer William S. Burroughs, editors Brian Alessandro and Tom Cardamone make a pitch for Burroughs’ place in the “gay canon,” arguing that the novelist “has been sainted by the literary establishment in general but not the gay literati in particular.”

No doubt this exclusion stems partly from Burroughs’ unflattering and even troubling depictions of homosexuals and their activities. In Queer, he calls gay men “fags” and “queens,” while the main character, Lee, comes across as pathetic in his desperate pursuit of a younger straight man. The gay sex in The Wild Boys is between teenage boys and quickly feels repetitive, as they’re always doing it in the same position, and the language scarcely varies from scene to scene. Burroughs’ personal life as a longtime drug addict who accidentally killed his common-law wife also makes his role as a literary hero problematical. As Fran Lebowitz remarks in her interview: “Killing your wife should never be allowed, okay?”

Burroughs’ status as a rebel, a gay man, and a drug addict who wrote openly about his experiences found great appeal among writers and musicians, especially in the punk and grunge movements. In “No Holes for Pigeons,” Christopher Stoddard highlights Burroughs’ descriptions in Junky of the repressive tactics that many states employed to drive out drug users. Debbie Harry and Chris Stein of Blondie remember how “not judgmental” he was in their conversations, willing to talk about anything.

Burroughs’ status as a rebel, a gay man, and a drug addict who wrote openly about his experiences found great appeal among writers and musicians, especially in the punk and grunge movements. In “No Holes for Pigeons,” Christopher Stoddard highlights Burroughs’ descriptions in Junky of the repressive tactics that many states employed to drive out drug users. Debbie Harry and Chris Stein of Blondie remember how “not judgmental” he was in their conversations, willing to talk about anything.

Several essays make intriguing arguments. Paul Russell, in “The Wild Boys,” observes that the sex scenes in the novel of that name are monotonous and repetitive, and he wonders if this was a way for the author to work through his own sexual obsessions. However, he also admits that he dropped this novel from his course on gay literature because students had great difficulty finding its merits, complaining that it “confirms everybody’s worst fears” about gay men. In “Queering Chaos,” Sven Davisson suggests that the sex scenes in The Wild Boys serve as mystic rituals. Burroughs was certainly a devotee of the occult, and the novel is subtitled “A Book of the Dead,” referring to the ancient Egyptian guide to the underworld.

Other essays feel more like experimental fiction. Jessica Rowshandel, in “Language Is a Virus from Outer Space: Divining Burroughs,” conducts a séance with Burroughs, who speaks in words drawn from his own works in “cut-up” style, which are then “interpreted” back into an intelligible form. A great deal of interpretation occurs from the “original” responses to the translations. In “Protoplasm,” Xan Price, in a letter to Burroughs (who’s addressed as “Pappy”), describes his sexual experience with a homeless man as a drug-induced mystical communion.

James Grauerholz’ “Birthday Ode” to Allen Ginsberg feels like an odd inclusion. As Burroughs’ business manager and lover, Grauerholz undoubtedly has stories to tell. Interviews with figures like author Samuel R. Delany and filmmaker David Cronenberg shed light on Burroughs as a person, although as verbatim transcriptions they feel somewhat clunky and repetitive. This collection should bring readers back to Burroughs’ own work, so they can decide for themselves where he stands in gay literature.

Charles Green is a writer based in Annapolis, Maryland.