THE RISE UP EXHIBIT at the Newseum in Washington, D.C., begins when you step off the glass elevator on the sixth floor with a video showing mostly young people introducing themselves as nonbinary, cisgender, gender-fluid, etc.—O brave new world!—but on the other side of that display is a wooden wall inscribed with headlines from earlier times.

“Perverts” seems to have been the most popular term. “Perverts Called Government Peril: Gabrielson, GOP Chief, Says They Are as Dangerous as Reds” on a 1950 issue of The New York Times. Or, in the L.A. Times of March 29, 1950: “Congress Hears 5000 Perverts Infest Capital.” The verb “infest” seems to allude to rats or cockroaches, but there were other terms as well. In The Atlanta Constitution on Nov. 6, 1954: “1500 Sex Deviates Roam Streets Here: Alverson and Hoover Warn Parents on Child Molesters.” The Chicago Daily Tribune on April, 2, 1953: “Begin Purging State Dept. of Homosexuals: Wasters, Subversives, Target of Senators.” The Atlanta Constitution in 1958: “Doctors Look on Sex Deviation as Sickness Like Dope Addiction.” In 1961, the PBS station in San Francisco broadcast a show called The Rejected, which seems sympathetic in comparison. So, summing up, we have: perverts, Reds, wasters, subversives, sex deviates, child molesters, dope addicts, and an allusion to rodents and/or insects. It’s a relief to laugh at The New York Daily News’ metaphor for the Stonewall riots: “Homo Nest Raided, Queen Bees Stinging Mad.”

Rise Up certainly includes the gay press—starting with One, the gay magazine put out by the Mattachine Society, and The Ladder, published by the Daughters of Bilitis, all the way to The New York Native, Frontiers, The Advocate, and The Washington Blade. Even more striking are the covers of the national news magazines that reflect the evolution of American attitudes toward homosexuals. A 1969 Time cover announces “The Homosexual in America.” In 1975, we get a photograph of Leonard Matlovitch; in 1997 Ellen DeGeneres (“Yep, I’m Gay”). Newsweek puts Barney Frank on the cover when he comes out. Then the theme becomes martial: Newsweek features Anita Bryant on a 1977 cover to highlight “The Battle Over Gay Rights.” “The War over Gays,” Time calls it in 1998, when Matthew Shepard was murdered. As late as 2015, when Indiana’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act is signed (by Governor Mike Pence), it’s still “Freedom Fight: The Attack on Gay Rights v. The Attack on Believers.” In between, we have the plague, which two Newsweek covers bookend: “Epidemic” (1983) and “The End of AIDS?” in 1996. And at the very start of the exhibit we have Caitlyn Jenner on the cover of Vanity Fair.

Opposite the Vanity Fair cover is a bench from which one can watch a short film on the history of gay representation in movies and on TV, which runs from Franklin Pangborn camping it up with a feather duster to Will & Grace, with Tom Hanks showing his KS lesions in Philadelphia in between. On the adjacent wall are posters of other cultural landmarks. In 1970: The Boys in the Band. 1985: Rock Hudson. 1993: Angels in America. 1994: Pedro Zamora (of the reality show The Real World) on the cover of Poz magazine, after revealing he has HIV. (He died later that year.) 2005: Brokeback Mountain.

This first part of the exhibit also includes a lexicon defining words like bisexual, drag queen, cross-dresser, queer, and transitioning that is meant to help the lay person, I guess, understand what they’re dealing with. Here “homosexual” is defined as “a clinical term” that is “now considered derogatory to many.” News to me, since I’ve been using it to avoid having to choose between “gay” (old hat) and “queer” (too harsh), though The New York Times, which for years would not permit the word “gay,” is now using “queer.” In this exhibit, “queer” is defined as an erstwhile insult that has been reclaimed, but it’s still a word that causes me to flinch—along with the old chestnut that appears in a photograph of a bar in Los Angeles with a sign on the wall that says “faggots—stay out.”

Things go by at a fast clip: Harry Hay founds the Mattachine Society, Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon the Daughters of Bilitis; Rita Mae Brown shows up at a NOW meeting in a T-shirt that says “Lavender Menace” after Betty Friedan accused lesbians of infiltrating the women’s movement; Anita Bryant removes the pie a gay activist has just thrown in her face at a press conference in Des Moines; the Air Force discharges Leonard Matlovich for being gay; then AIDS, ACT UP, Lawrence v. Texas, “Don’t ask, don’t tell,” same-sex marriage. Things I didn’t know: the title Rubyfruit Jungle is a euphemism for female genitalia; the first thing the queens threw at the police on the night of Stonewall were pennies; the uprising lasted six days; Craig Rodwell, who founded the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop on Christopher Street, also organized the Stonewall anniversary parade in 1970. Some charming trivia: when the lesbian magazine The Ladder was being published, gay women would hold “Ladder parties” at which they read aloud from the latest issue. (Oh, for such devotion now!) When the Supreme Court struck down the law against sodomy in Lawrence v. Texas, Antonin Scalia predicted it would open the door to gay marriage, and twelve years later he was proven right.

And then there is a little booklet called the S.I.R. Pocket Lawyer, which was published by the Society for Individual Rights in San Francisco (founded in 1964) so that homosexuals would know what to do when arrested while cruising. Common practice was to not contest the charge, since that would eject the person from the closet, though as far back as 1952, when Dale Jennings was picked up for “lewd vagrancy” in Los Angeles, the Mattachine Society persuaded him to fight the charges and the courts ruled in his favor.

The main part of this small but intense exhibit closes with a wall of photographs of well-known LGBT people, including Caitlyn Jenner and Chaz Bono, which returns us to the nonbinary present. Coincidentally, the day I visited, The New York Times carried a long profile of nonbinary youths in the rural South—along with news of an apology for the Stonewall raid from the New York City Police Department.

Rise Up is timed to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, but one thing you take away from it is that New York was hardly the origin of the gay rights movement. It really began in Los Angeles and then spread to Washington, D.C. The Mattachine society, named after a medieval French group that challenged church and state, was founded in L.A. in 1950. Its second chapter was opened in 1961 by Frank Kameny in D.C., where he and his colleagues—dressed in suits and ties or modest dresses—picketed the White House in 1965. The exhibit Rise Up is not primarily about Stonewall itself; it’s about what preceded and what followed it.

The Newseum is located on Pennsylvania Avenue opposite the National Gallery of Art in a splendid building that opened a few years ago. But because it has not been able to sustain itself financially (adult tickets are $25 in a city where most museums are free), it has sold the building to Johns Hopkins University and will be closing on December 31st. The day I went to see Rise Up, however, it was jammed—mostly with kids.

So startled was I by these girls with ponytails and backpacks and their male counterparts that I stepped into the hall for a moment to put my hearing aids in so I could hear the wisecracks they were going to make about it. Alas, even with my Oticons in place, the eavesdropping was a disappointment; the Lolitas tended to huddle, the Tadzios to move so fast that one couldn’t track them. But I kept wondering: what could they possibly make of all this? Was Rise Up for them just a civics lesson? Watching Ellen DeGeneres come out on TV was a trio beside me composed of a boy with glasses looking up at a taller boy who stood beside what was already apparently an alpha male. “Just how old are you?” I wanted to ask, for I can no longer tell, but in these paranoid times, that might have seemed predatory. The only conversation I began occurred when an adolescent with curly dark hair complained that the voice recognition on an interactive video screen wasn’t working; but the minute I stepped forward to engage him in conversation, a teacher appeared out of nowhere, grabbed him by the arm, and snatched him away. “Come back!” I imagined shouting. “You’re depriving your student of an opportunity to interact with the real thing—an actual homosexual!” But I didn’t. Instead I was left standing there, a stranger with candy, an old man thinking about Death in Venice.

So startled was I by these girls with ponytails and backpacks and their male counterparts that I stepped into the hall for a moment to put my hearing aids in so I could hear the wisecracks they were going to make about it. Alas, even with my Oticons in place, the eavesdropping was a disappointment; the Lolitas tended to huddle, the Tadzios to move so fast that one couldn’t track them. But I kept wondering: what could they possibly make of all this? Was Rise Up for them just a civics lesson? Watching Ellen DeGeneres come out on TV was a trio beside me composed of a boy with glasses looking up at a taller boy who stood beside what was already apparently an alpha male. “Just how old are you?” I wanted to ask, for I can no longer tell, but in these paranoid times, that might have seemed predatory. The only conversation I began occurred when an adolescent with curly dark hair complained that the voice recognition on an interactive video screen wasn’t working; but the minute I stepped forward to engage him in conversation, a teacher appeared out of nowhere, grabbed him by the arm, and snatched him away. “Come back!” I imagined shouting. “You’re depriving your student of an opportunity to interact with the real thing—an actual homosexual!” But I didn’t. Instead I was left standing there, a stranger with candy, an old man thinking about Death in Venice.

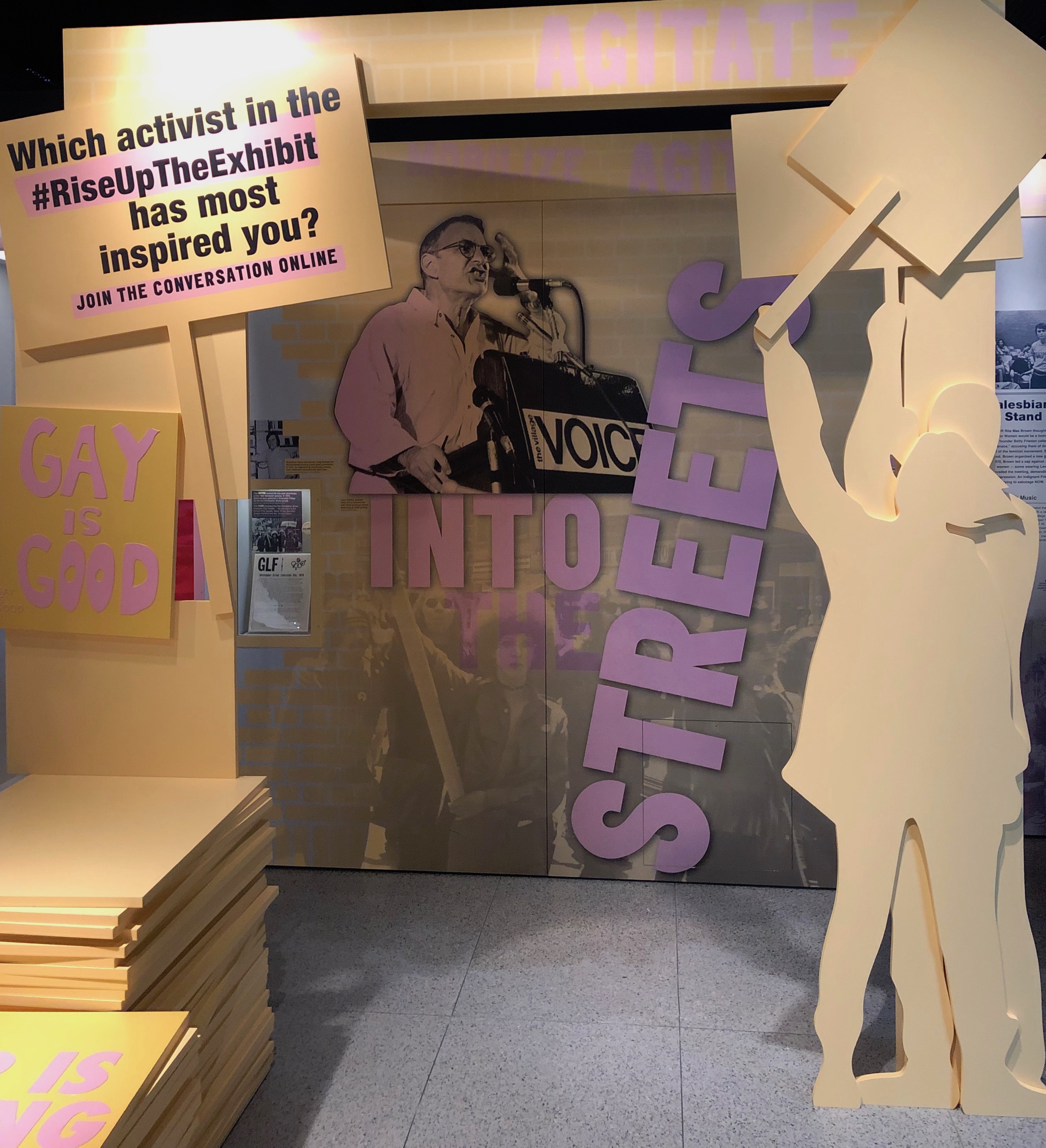

Yet clearly this exhibit is for these kids. There are several interactive videos that ask “What would you do?” and “What do you know?” What would you do if you were a baker and a gay couple asked you to bake a cake? What would you do if you were gay in the military—tell people or keep it a secret? And so on. Above the stack of ACT UP placards in the center of the room is a question: “Which activist in the #RiseUpTheExhibit has most inspired you?” That’s one thing Rise Up is surely about: inoculating the next generation against homophobia.

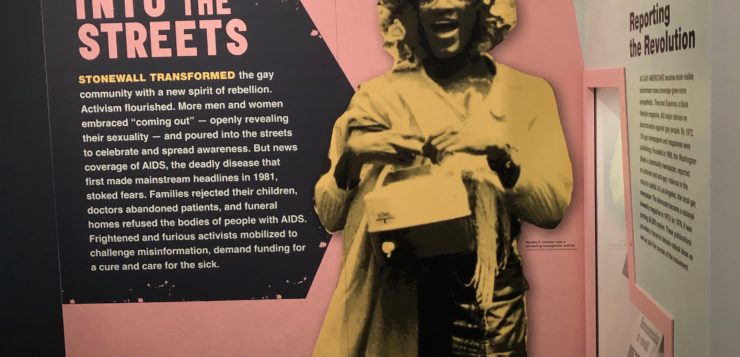

Down some stairs to the next floor, into the darkness where the teacher has taken his stray student, I think I’ve left the exhibit, but there is more. Halfway along a vast display of old newspapers I stop at a video screen that tells the story of Leroy Aarons, the editor of The Oakland Tribune, who in 1990 announced he was gay at a convention of journalists, quit his job, and founded the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association (nlgja). And then in the adjacent theater I come upon “the 100-foot screen” showing a short film called “Into the Streets,” which traces, with archival video footage and interviews with gay activists, the history of the gay movement. Here I run into Anita Bryant again—claiming on television that homosexuals “can become ex-homosexuals, just the way murderers can become ex-murderers, and thieves ex-thieves.” It’s still astonishing. The role of the Mattachine Society is not the only thing I failed to appreciate before coming here; the other is the importance of Bryant to the gay rights movement. It was Anita, one of the talking heads in the film observes, who was the first person to get gay people “into the streets,” and that provided a dry run for the civil disobedience that would follow during the plague years.

Down some stairs to the next floor, into the darkness where the teacher has taken his stray student, I think I’ve left the exhibit, but there is more. Halfway along a vast display of old newspapers I stop at a video screen that tells the story of Leroy Aarons, the editor of The Oakland Tribune, who in 1990 announced he was gay at a convention of journalists, quit his job, and founded the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association (nlgja). And then in the adjacent theater I come upon “the 100-foot screen” showing a short film called “Into the Streets,” which traces, with archival video footage and interviews with gay activists, the history of the gay movement. Here I run into Anita Bryant again—claiming on television that homosexuals “can become ex-homosexuals, just the way murderers can become ex-murderers, and thieves ex-thieves.” It’s still astonishing. The role of the Mattachine Society is not the only thing I failed to appreciate before coming here; the other is the importance of Bryant to the gay rights movement. It was Anita, one of the talking heads in the film observes, who was the first person to get gay people “into the streets,” and that provided a dry run for the civil disobedience that would follow during the plague years.

If one was wondering why the Newseum mounted this exhibit, “Into the Streets” answers the question: it views American gay history as a civil rights movement. The 1960s was a time when women and blacks were being liberated, notes activist Mark Segal, so “Why not us?” Someone else calls what Harry Hay began “the last civil rights movement of the 20th century.” Attorney Linda Hirshman says ACT UP was “the single most effective social movement since Abolition.” All this seems a bit grandiose, so it’s a relief when Eric Marcus ends his list of the five or six reasons the riot occurred that night at the Stonewall Inn with “And there was a full moon.”

There is one short clip in the film of two men starting to weep as the names of the dead are read on the Mall during the display of the AIDS quilt, but there is no attempt to memorialize the lost in Rise Up, though Linda Hirshman makes an excellent point when she says that it was AIDS and gay people’s response to it that gave us the social and political capital to press for issues like same-sex marriage.

Elsewhere in the Newseum, I encounter the most jarring of all the exhibits, a series of Pulitzer Prize-winning photographs, which start with emaciated babies in Yemen and, among other unforgettable images, include the most homoerotic thing I have seen all morning—a photograph of two electrical linemen in Jacksonville, Florida. One has just been electrocuted and is lying limp across the wires—the other has put his mouth on his unconscious colleague’s lips to breathe air into his lungs—a CPR maneuver called “the Kiss of Life.” Like Rise Up, it’s a strange blend of the erotic and the heroic.

Andrew Holleran’s fiction includesDancer from the Dance, Grief, andThe Beauty of Men.