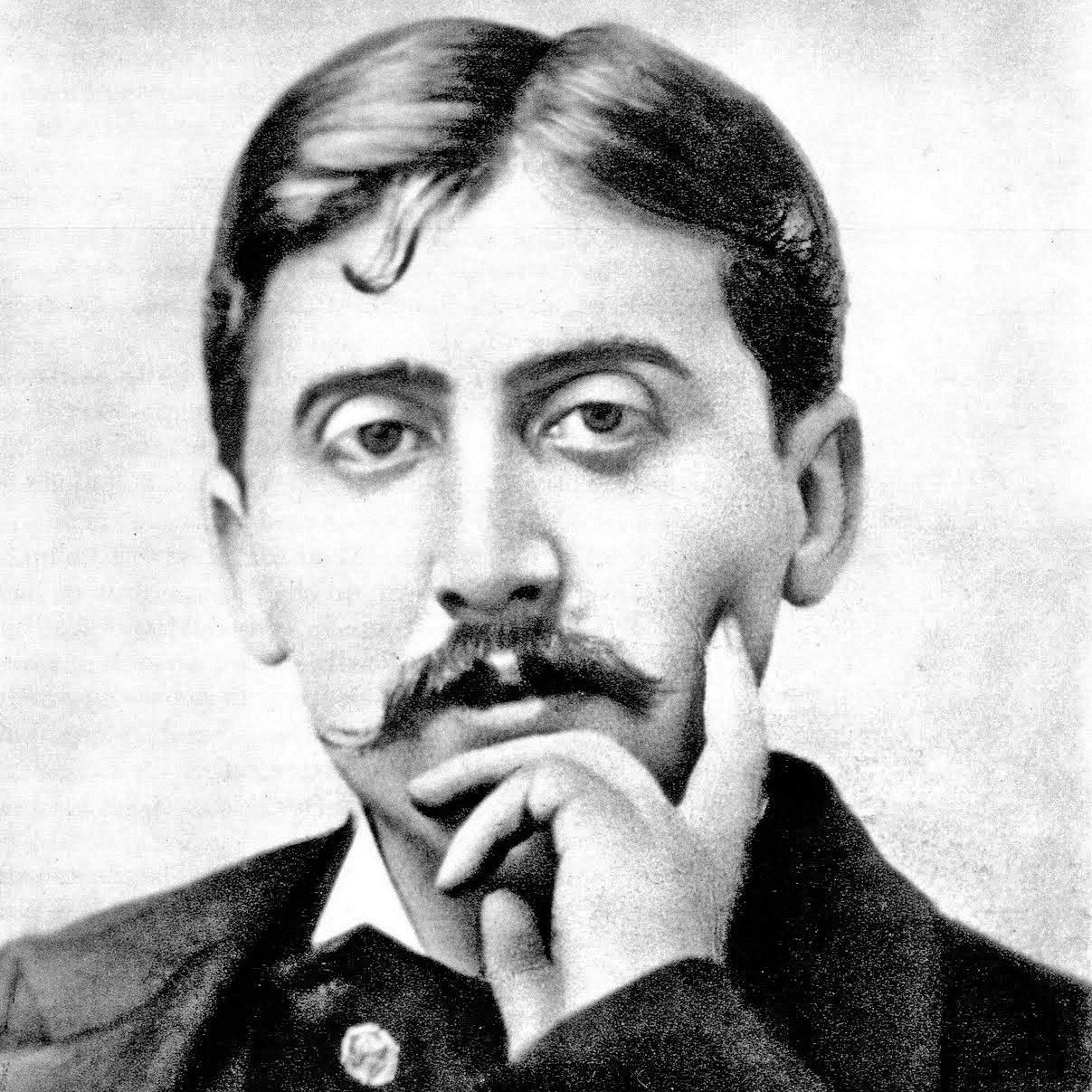

MARCEL PROUST’S 3,000-page narrative À la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time) is often cited as one of the great modern novels, as well as one of the foundations of Modernism. That it was. It is also cited as one of the most important gay novels. Whether its artistic importance still makes its seven tomes of often uncritical homophobia one of our community’s most important literary works, I’m not so sure. As I read Lucy Raitz’ new translation of part of it, I recalled Harvey Fierstein being quoted as saying in The Celluloid Closet (1995) that he was happy to see even negative portrayals of gay men in films, because he believed in “visibility at any cost.” I’m not sure how many LGBT people today would go along with this viewpoint.

It’s one thing to cringe at a homophobic scene in a favorite old movie; it’s over in a minute or two. Swann in Love ends with pages of Swann’s revulsion at the thought that the woman he loves, Odette de Crécy, might have had sex with other women. Other parts of the novel are equally homophobic. Is there a point at which the work’s artistic innovation ceases to compensate for its repeated anti-queer morality, at least to the extent that it forfeits its status as an “important gay book”?

A hundred years ago, C. K. Scott-Moncrieff, himself a gay man and friend of gay writers like Wilfred Owen and Noel Coward, evidently thought so. He devoted the last eight years of his relatively short life to produce the first English translation of the Recherche. This translation has been revised three times, most recently by Proust scholar and biographer William C. Carter, based on the corrected new French edition that Jean-Yves Tadié brought out in the 1980s. Penguin brought out a completely new translation of Tadié’s edition using several translators starting in the 1990s. Oxford University Press published yet a third translation of just the middle third of the first volume, Swann in Love, by Brian Nelson, in 2018.

A hundred years ago, C. K. Scott-Moncrieff, himself a gay man and friend of gay writers like Wilfred Owen and Noel Coward, evidently thought so. He devoted the last eight years of his relatively short life to produce the first English translation of the Recherche. This translation has been revised three times, most recently by Proust scholar and biographer William C. Carter, based on the corrected new French edition that Jean-Yves Tadié brought out in the 1980s. Penguin brought out a completely new translation of Tadié’s edition using several translators starting in the 1990s. Oxford University Press published yet a third translation of just the middle third of the first volume, Swann in Love, by Brian Nelson, in 2018.

So, one might ask, were there particular reasons for a fourth translation of this more-or-less stand-alone section of the work? I had assumed that, as with the Penguin and Oxford translations, there might be a translator’s preface detailing them. I was wrong. There are 47 brief endnotes clarifying some of the literary and historical references in the text, but that is all. Some introductory material might have helped readers not familiar with the late 19th-century Parisian world in which it takes place. I would assume the translator, Lucy Raitz, used the new Tadié edition, but there’s no mention of it on the verso of the title page, just the 1913 Grasset first edition, which must be out of copyright and which was full of mistakes that Proust corrected for a later Gallimard edition (and which he kept reworking until his death).

The blurb on the dust jacket says that Swann and Odette continue to meet “in the drawing rooms and theaters of Parisian high society.” But Odette never gains entrance into Parisian high society, the aristocracy, only the salon of the bourgeois Verdurins. The blurb also says that Swann in Love is “sublimely witty.” But since there are few high-society settings in this part of the novel, there isn’t much of what Proust elsewhere presented as wit, just the failed efforts at aping it by the Verdurins’ routinely ridiculed bourgeois habitués.

This is primarily a tale of one heterosexual man’s obsessive love and even more obsessive jealousy for a woman he eventually dismisses as his social inferior: “To think that I wasted years of my life, that I wanted to die, that I had my greatest love, for a woman to whom I wasn’t attracted, who wasn’t my type!” (Yes, Proust’s “wit” is often classist.)

Why someone should opt for this translation of Swann in Love over the Penguin or Oxford or Carter’s reworking of the Scott-Moncrieff the volume does not say. But neither can I say why someone who has decided they want to make the effort to read Proust—and it takes effort—should start with this section, in the original or translation. There are other parts that, for me at least, still justify putting up with its classism and homophobia. ____________________________________________________