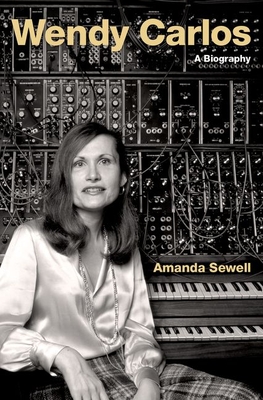

WENDY CARLOS

WENDY CARLOS

by Amanda Sewell

Oxford Univ. Press. 264 pages, $34.95

AS AN ADOLESCENT in the early 1970s, I remember saving up my allowance to buy vinyl LPs of movie music, one of which included the theme from A Clockwork Orange (1971). The film was rated “R,” so I hadn’t seen it, but it evoked the sense of something totally new and forbidden. The cut on the LP—a synthesized version of Purcell’s Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary—was unlike anything I had ever heard before. To later generations for whom synthesizer sounds are unremarkable, it’s difficult to convey how strange and futuristic these sounds were. Later, when I was in college and heard that the composer of that music, Walter Carlos, had undergone gender confirmation surgery and was now living as a woman named Wendy, it was another kind of shock. Such a transformation was simply unheard of at the time.

Before creating the music for Kubrick’s film, Carlos had released an album called Switched-On Bach that featured a number of Bach’s works “electrified” via synthesizer. To this day, it is still the bestselling classical album of all time. The synthesizer was the invention of an engineer named Robert Moog, who had personally delivered one of his earliest modules to Carlos, who spent an entire weekend helping to get it set up. It would change both of their lives forever. Together they would develop and enhance the cutting-edge technology that has had such an impact on music ever since.

The Moog Synthesizer could only produce one note at a time. To create the “switched-on” effect, Carlos painstakingly created each note, sequenced notes into lines, and then stacked them up, sometimes layering as many as six separate lines to create Bach’s counterpoints and harmonies. But there was also a performance virtuosity to Carlos’ recordings. No less a fan than Glenn Gould called Switched-On Bach the “record of the decade,” singling out its “unfailing musicality” and claiming it was one of the greatest feats ever achieved in keyboard performance. The album won three Grammys in 1969, including Best Classical Performance and Classical Album of the Year. A subsequent album, featuring Carlos’ version of the Brandenburg Concerto No. 4, was acclaimed by Gould as “the finest performance of any of the Brandenburgs—live, canned, or intuited—I’ve ever heard.”

Carlos (born in 1939) was an innovator from the start. She began piano lessons at the age of six, but because the family had no money, her father drew a keyboard on a piece of paper for her to practice. At the age of fourteen, Carlos won a Westinghouse Science competition by creating her own computer. Intrigued early on by tape composers like Pierre Henry, she started experimenting on her own. She also became fascinated with the tunings for various keys and, after the family was finally able to purchase an instrument, would often retune it in experimental intervals of her own. In college, she and her colleagues created a library of nearly 100 different pitches, all of which fell within the same octave.

This was exactly the territory that Bach had explored centuries before in The Well-Tempered Clavier: determining his own tunings, then creating a work for each key. Later, Carlos would release an album of her own called The Well-Tempered Synthesizer, continuing to experiment and improve upon the capabilities of the available technology. She expected other musicians would follow her lead in this new electronic landscape. She even argued that, if Bach were alive today, he would probably have worked with synthesizers. That no such movement occurred was a source of endless frustration to her, as was the fact that so many interviewers chose to focus less on her musical innovations than on her personal transformation.

It should be noted that Carlos herself did not participate in this biography, and nor did anyone close to her—a fact the author is very upfront about. Since the biography came out, Carlos has written on her website that it “belongs on the fiction shelf. … Don’t recognize myself anywhere in there.” Throughout her life, Carlos has fought to be treated simply as a musician without reference to her personal history. Sewell largely honors this wish and makes a convincing case for regarding Carlos as one of the major musical figures of the 20th century.

If Carlos’ musicianship is easy to appreciate, her status as a composer is more difficult to assess. For starters, much of her output is difficult to find in any format other than used CDs. She has continued to compose film scores and has released other original music. Between 1998 and 2004, she released remastered versions of much of her work on CDs. In 2005, she released Rediscovering Lost Scores, which contained 61 tracks of film music that had never been released before, including music Kubrick hadn’t used in The Shining. Carlos has never embraced MP3 downloads, considering the sound “thrown away” because of the compressed format. Hence, much of her work has disappeared from view. A recording of her complete score for A Clockwork Orange, which I was able to obtain, still strikes me as brilliant and otherworldly, just as it did in the early 70s.

If nothing else, then, one hopes that Sewell’s book will help to restore Carlos’ music to the foreground, where perhaps it can finally be assessed on its own merits. Until we have Carlos’ own autobiography, this book is a good place to start.

Dale Boyer’s is the author ofThe Dandelion Cloud, Thornton Stories, and Justin & the Magic Stone.