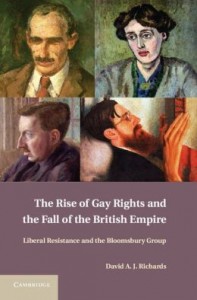

The Rise of Gay Rights and the Fall of the British Empire: Liberal Resistance and the Bloomsbury Group

The Rise of Gay Rights and the Fall of the British Empire: Liberal Resistance and the Bloomsbury Group

by David A. J. Richards

Cambridge University Press. 280 pages, $95.

WHEN PRESIDENT OBAMA spoke in Senegal a few months ago, he confirmed his belief in the basic human rights of sexual minorities. But the President of Senegal, Macky Sall, rebuffed Obama’s universalist claim, stating that “we have different traditions.” As in many other countries in Africa, the leader of Senegal contends that homosexuality is an immoral relic of Western imperialism and not indigenous to the traditions of Africa.

David Richards engages the tension between imperialism and gay rights and offers an intriguing thesis: the emergence of gay rights in England (and the West more generally) was a result of a new ethical awareness about the problem of patriarchy, an indispensable pillar in the logic of imperialism. The same awareness gave rise to the concept of gay rights, which was predicated on a critique of patriarchy and thus of empire building. In essence, if imperialism is the denial of ethical practices related to human rights, then the rise of gay consciousness is of a piece with the anti-imperialist urge to build a more inclusive, democratic society.

Richards, a professor of law at NYU who has written much on the legal history of gay and lesbian rights, focuses on the constellation of writers, artists, and scholars of the Bloomsbury group and looks at the ways in which they resisted the sexual and gender codes of the era, which he calls the “love laws” that targeted all manner of intimate relationships. He refers to the unconventional relationships of these artists and writers as a “resistance movement” that set in place an ethical awareness of patriarchy’s vulnerabilities. These would increasingly become a matter of public discussion after World War II, when the rights of sexual minorities became a legal and parliamentary concern. The book reaches far beyond Bloomsbury in later chapters on gay rights in former British colonies and in a final chapter on “universal human rights.” But ultimately it fails to offer an understanding of the tensions between imperialism and gay rights at the heart of the book’s premise. Throughout, Richards mixes legal and political histories and literary analysis with a heavy dose of feminist psychoanalysis to produce a confusing confection of conclusions. For example, in considering the impact of patriarchy in establishing imperial ambitions, he notes that empire building required a separation of parent and child, fostering a “traumatic loss in intimate relationships” and “suppressing personal voice.” But it’s not clear why we need psychoanalysis to uncover the problems of imperialism’s patriarchic foundations. It is true that the men and women of Bloomsbury were acutely aware of psychology’s modern appeal. Indeed, a sensitivity to class structures informed by socialist political theories was intricately linked to the critique of patriarchy and empire by many in the Bloomsbury group. And, as a practical matter, we know from recent scholarship that they regarded illicit sexual activity as an element of resistance to patriarchal authority. In addition, experiences and resistance to gender and sexual codes varied by class, a reality that Richards doesn’t account for in his focus on the middle-class enclave of Bloomsbury. Indeed, throughout 20th-century England, policing the “love laws” was often tied to class boundaries. Richards concludes with a broader analysis of gay rights within the context of reactionary claims against homosexuality espoused by such leaders as President Sall of Senegal. Gay rights, argues Richards, is a result of a more democratizing society, and efforts to dismiss it as part of imperialism’s stranglehold underscores such regimes’ dictatorial goals. Imperialism, with its necessary claims of an abusive and violent patriarchy, cannot coexist with legal rights for sexual minorities. And yet, it’s not at all clear how this model of the rise of gay rights and the decline of empire can account for the last few decades in the U.S., where a growing tolerance of sexual minorities has been accompanied by a more aggressive American foreign policy. This exception throws into doubt the book’s larger claims. In the end, we are left with more uncertainties than insights into the issues that this book tries to illuminate. James Polchin teaches writing at NYU, writes a visual arts column at TheSmartSet.com, and edits the website WritinginPublic.com.