Translated by Mark Oshima

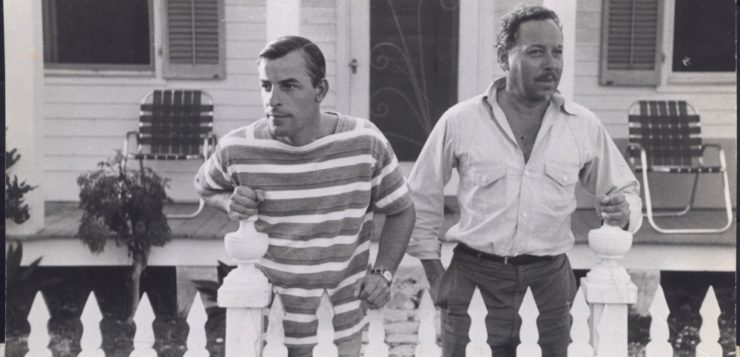

TENNESSEE WILLIAMS and Yukio Mishima talked about their work and work routines in 1959. The conversation was lightly moderated by Williams’ life partner Frank Merlo, whom Mishima refers to as Williams’ “secretary.” Also present was Williams’ friend Donald Richie, who chimes in near the end.

The discussion was originally published in Geijutsu Shinchō (“Shinchō Arts”), November, Showa 34 (1959). The piece ran under the heading “Geki Sakka no Mita Nihon”(“Japan as Seen by a Playwright”).

1. After Seeing a Dress Rehearsal for a Japanese Production ofA Streetcar Named Desire.

Yukio Mishima: I understand that you went to a rehearsal of the Shichiyokai production of “A Streetcar Named Desire.” How was it? Tennessee Williams: I thought that the actors were all very good. TW: I was surprised that it was so close to the American production. I had hoped that it would not be so American, but more Japanese. It would have been interesting to see a production more in kabuki style. (Williams does an imitation of kabuki movement.) YM: I think that actually that is the Japanese way. Japanese like the original form, so in kabuki, we treasure the way the original actor did it. We like the original. So, doing a play in exactly the same way as it is done abroad is none other than the Japanese way of doing things. With a Chekov play, we produce it just the way you would see it with the Moscow Art Theater. TW: I realized that they were being very faithful to the original production. During the rehearsal, I was asked all kinds of questions about lines they didn’t understand and things like that. Frank Merlo: I don’t know if Tennessee is aware that most young Japanese don’t like kabuki. YM: The number of people that like kabuki has gone down as a percentage of the whole from what it was in the past, but there still are quite a few who do like kabuki. FM: I was surprised that many young people don’t understand kabuki! YM: How were the actors in the rehearsal of A Streetcar Named Desire that you saw today? TW: The actor playing Stanley was very good. He was better than the actress playing Blanche. Just now I mentioned the idea of kabuki production techniques. I like the passageway through the audience where actors make their entrances. In fact, I used that when Camino Real was performed. But the New York audience didn’t like this idea much. The audience was preoccupied by the fear that the actors would step on their feet. The director was Elia Kazan, but there were strong opinions for and against this production technique, which was annoying. Elia Kazan has directed most of my plays, but with Summer and Smoke, I had a woman direct it, Margo Jones, who often stages things as theater in the round. For this production, I thought of having a screen at the back of the stage and had film images projected on it. This was not very successful either. YM: Camino Real hasn’t been produced in Japan yet, but I think that production technique would make it very accessible to Japanese. By the way, Tennessee, with Cat on a Hot Tin Roof you made a rewritten version incorporating Elia Kazan’s ideas. But I think the original version is better. TW: I’ve very glad to hear you say that. Actually, that’s what I think too. YM: What do you think of this idea that a play can be rewritten according to the ideas of the director? TW: Well first, I have great respect for the position of the director, and I take his opinions very seriously. Because I believe this, I think that even if the idea does not work in the end, the playwright should be prepared to make additions and rewrite. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is an example of when this didn’t work out. YM: How much do you participate in the direction of your plays? TW: As a rule, I don’t go to rehearsals. If I show up at a rehearsal, it would inevitably encroach on the freedom of the director, and I don’t want to violate the rights of another person. That would be like peeking into the married life of another couple. YM: Do you intend to go on working for Broadway? TW: I don’t have much interest in Broadway anymore. In the future, I want to work Off-Broadway. [Note by YM: Plays by Tennessee Williams like Summer and Smoke failed on Broadway and then became a success Off-Broadway. Last year when he presented a set of two plays including Suddenly, Last Summer under the title Garden District, it was a sensation because it was the first time for such a major playwright to write a new play for Off-Broadway. He was very satisfied with this success and it seems to have increased his interest in working for Off-Broadway, which was free of commercialism. But his current play Sweet Bird of Youth is a big success on Broadway.] YM: I understand that the protagonist of your current play Sweet Bird of Youth is a retired actress. I remember seeing people like that in Florida. Your actors’ union has a well-developed unemployment insurance system so actors can relax in the sun and wait for their next part. A retired actress has more money than she knows what to do with. I understand that Sweet Bird of Youth is about an actress like that and a gigolo. But in Japan, actors are on stage until they die. Partly that is because they want to be and partly because that’s the only way that they can survive. They don’t let you retire so easily here. TW: The actors’ union in America does have a good insurance program and does other things to protect their livelihood. And that is not just for actors, but for playwrights too. By the way, how were you paid for your Onna wa Senryo Sarenai (“Women Never Be Captured”)? Was it a share of the profits? Or was it a lump sum? YM: It was a lump sum, this much. TW: That’s unbelievably little! Why don’t you form a union and defend your rights? YM: Japanese theater has traditionally had a system of one-month programs, so it’s very difficult to break even. For contemporary theater, you can’t say that it is a commercial theater. FM: Italy also has a one-month system. Traditionally Italy doesn’t have long runs either. 2. Themes of Tennessee Williams’ Plays YM: Tennessee, your three recent plays, Camino Real, Orpheus Descending, and Suddenly, Last Summer all treat the same theme, don’t they, a theme that you have been writing about from long ago? I believe that this is about the ideal of a sacrifice and the tragic hero. The idea of the tragic hero stems from the ancient ritual of sacrifice, so I believe that your plays re-enact the ideals not of tragedy but of an even older stage. I find that fascinating. TW: I suppose that what they have in common is that they are about someone who is not necessarily intelligent, but is sensitive and easily hurt, in other words, someone who is excessively romantic. This personality gradually leads this character to become the protagonist of a tragedy. Blanche in A Streetcar Named Desire is the archetypical example. YM: You mean the archetypical example in terms of that point. TW: When a young person with a pure soul runs into something extremely powerful, they are cruelly crushed. That becomes a tragedy. But I’ve written enough plays like that, and this time I wanted to take the opposite tack. So Sweet Bird of Youth is a tragedy, but I made the female protagonist an old actress who has already seen everything. YM: I think it’s something like this. Someone who has a romantic temperament and is sensitive and fragile gradually is destroyed. In other words, your romantic heroes eventually are sacrificed, and, as you said, the clearest example of this is A Streetcar Named Desire. But now you are trying to make a shift and instead of sacrifice, you want to write a drama of resurrection. So, you made the protagonist a tough old actress. So, she doesn’t go to destruction. Perhaps you’ve lost interest in writing about sacrifice and destruction. And I think you can say the same thing about an earlier play, The Rose Tattoo. TW: The Rose Tattoo is a comedy, so the situation is a little different. The protagonist is extremely romantic. She is a comic version of Blanche in A Streetcar Named Desire. 3. The Similarities between Novels of the American South and Japanese Literature TW: Mr. Mishima, why don’t you write a new play and present it in America? I’m sure it would be a hit. Write a play and you can direct it. I’ll direct Kikuchi Kan’s Okujō no Kyōjin (“The Madman on the Roof”) and you can direct one of Yukio Mishima’s “Modern Noh Plays” and we’ll present them together. That would be interesting, wouldn’t it? YM: Kikuchi Kan’s plays are very simplified, and that’s something I like about them. Tennessee, now that you mention it, Okujō no Kyōjin is really the kind of play that you would like. The sensitivity and purity of the older brother on the roof and the purity of his younger brother who tries to protect him is the kind of motif that would not be out of place in one of your plays. TW: I’ve only read the play, but I liked it a lot. While I was reading it I started to think that I would really like to put it on in America. By the way, Mr. Mishima, I have a very strong feeling that the literature of the American South and Japanese literature are somehow similar. What do you think? The more I read by Japanese writers, the more I think that. An over-refined sensitivity and, because of that, a soul that finds life difficult—I think elements like that are extremely similar. Of course, the expression of this in America is much more direct and in Japan it is more indirect. In that, they are different. But I think that the concept of “reality” that you find in Japanese literature and the sense of tragedy is very close to the writing of the American South. For example, Dazai Osamu’s Ningen Shukkaku (“No Longer Human”) reminds me very much of the novels of Carson McCullers. The same is true of Dazai’s Shayō (“The Setting Sun”). When I read it, I noticed it had some of the special qualities of Southern literature. FM: Yes, that family is just like a Southern family. YM: Tennessee, you just mentioned Daizai Osamu, but is he someone that you respect? TW: I have a great deal of respect for him. YM: I can respect Dazai as an artist, but as a human being, as an individual, I really dislike him. I’m not saying that out of a feeling of rivalry as writers, I just can’t stand him. The first time I met him, he was slumped, dead drunk. TW: Is that unusual in Japan? In America, that’s normal! YM: The reason I dislike Dazai is because he had the sensibility of an extreme romantic. All he could do was to complain about things and resent other people. And he loudly proclaimed his weakness to everyone. That’s the kind of thing I can’t stand. He didn’t hide his sensitivity and how he was easily hurt. That was very painful for me to see. TW: I don’t think that is something you can hide. An artist is someone who wounds himself and cuts himself and takes the blood that flows from him and throws it onto other people. And he is someone who is always dreaming. YM: I like someone like you, Tennessee, with a definite personality. TW: You are the one with a definite personality! You would probably dislike my character. YM: No, I like it! TW: I can only be a nice person for three hours a day at most. After three hours, I’m really a terrible person. YM: But Tennessee, you always swim once a day. This is something Dazai couldn’t do. He could only do things that ruined his body. TW: When people see me, it’s always when I’m exhausted and usually drunk. And all my nerves are exposed. So, it’s difficult for me to show a good face to other people. Anyway, I work for three hours every day, and after that, I’m totally exhausted, so if I meet people after that, I’m very difficult. In a year, I only have five good days. That’s when I write my plays. All my plays are written in those good five days. 4. About Movies Made from Your Plays TW: I think that young contemporary Japanese writers are fixated on the concept of death. We can’t find hope in life as such. Hope is an insubstantial thing and can only be glimpsed in the moments of life. I think this is a place where you can find commonalities between novels from the American South and Japanese literature. YM: I believe that there is beauty in something going to its destruction. As you see in the South and in some periods of Japan. … But there is no meaning just in destruction, there has to be regeneration as well. This is why I think a constant theme in your plays is that something that is destroyed always returns to life. A person who has been sacrificed always, in some form, in the end is reborn. I think that is the most important constant theme in your plays. Because of this, I can understand why you like Dazai; it is also why I dislike Dazai. He could only think about destruction. He was a romanticist. Tennessee, the characters you write about may be romantics, but that does not mean that you yourself are a romanticist. 5. Homosexuality Must Not Be Used as a Sales Gimmick YM: Tennessee, from time to time, the question of homosexuality appears in your plays. Historically, Japan was very tolerant about homosexuality, but I believe that it was America that changed this. It was due to the puritanism brought by missionaries after the Meiji Restoration. TW: Ah, I see! In your novels, both homosexuality and heterosexuality are treated equally without partiality as a pure kind of love. That’s the way Japanese feel about that. When you write about love, that may be love between opposite genders or that may be between people of the same gender, but I think that the difference between them is very exaggerated. In America, male homosexuality is treated as something very unusual and there are many playwrights that use it to attract attention or shock the audience. But I’m not one of them. The only play that actually treats homosexuality directly is Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. But the play is not a play about male homosexuality. That is just one element to give a certain theatrical effect. The most important theme of the play is “mendacity.” YM: I thought that condemning mendacity and lying were very Christian ideas. TW: Not necessarily. Lying is one of the worst, most dangerous evils in human society. YM: Of course, I understand that, like when a politician lies. That’s a very big problem. But I still believe that the idea of “mendacity” is a very Christian idea. The ancient Greeks were not particularly afraid of mendacity. Often there is a contrast made between a morality of shame and a morality of conscience. The morality of conscience is something that is considered particularly important by Protestantism, in other words, a morality inside you. But a morality of shame is a morality of surface appearance: as long as the appearance is good, it’s all right. Japanese are like ancient Greeks in that respect, believing that truth is in the surface appearance. In other words, the difference between these two ways of thinking is whether you think that truth is outside or inside. So, the ancient Greeks and traditional Japanese believe that truth is on the outside. You think that truth is inside. So, I believe this is why we see “mendacity” differently from you. For Protestantism, truth is inside. Falsifying this interior truth is what “mendacity” is. Of course, I’m sure there was “mendacity” among the ancient Greeks. But I think that since they believed that truth was on the outside, they fundamentally believed that someone who was beautiful on the outside would also have a beautiful heart. TW: That’s certainly true. Even if you look at someone and really think it’s so, few people are actually going to say, “You look like you are about to die. You have one foot in the grave!” I have only been studying Japanese literature for a very short time, so I really have no right to say anything about it, but I get a strong feeling of an honor for truth. Recently I read Natsume Sōseki’s Kokoro, and I was very impressed. I think that Americans are liars. I hate lies as a plot against American culture. All artists plot against the culture of the country in which they were born. This is true of all artists. YM: What do you think of Marcel Proust? TW: I have always thought that Proust was trying to communicate truth. But I think that Gide was a hypocritical artist. YM: Absolutely! Richie: But I don’t think that Gide knew that he was a hypocrite. TW: Of course, no one condemns themselves for the character they were born with. I like Gide, for example his La Porte Étroite (Strait is the Gate). But when I read his diaries, I keep thinking, “What a hypocrite!” But I feel the opposite with Proust. Richie: And, of course, that made Proust a great man. TW: Yes. I think he was a very great man. And he was a tragic hero. I think that because he was such a great author, even when writing about something that violently disgusted him, like the Baron de Charlus, the sensitive reader can feel a kind of greatness in him. In fact, that’s the reason I deal with the Baron de Charlus in my Camino Real. He is almost a universal character. 6. What You Are Writing While Traveling YM: While you are traveling now, are you writing something? TW: I’m writing a new play. To give you an idea of the story, the central characters are a 97-year-old man and his middle-aged, unmarried granddaughter. The old man is a poet and his granddaughter is an artist. The two are traveling together. The old man recites his poetry to people that he encounters, and his granddaughter—she is a real artist—draws quick sketches of the people listening in order to make the money they need to survive. This is a story that happens as they stay at a hotel in Mexico after the end of the tourist season. The old man is gradually going blind, but he doesn’t want his granddaughter to know it. Moreover, he has had a stroke once, and that has affected his memory. The play is titled Night of the Iguana. Iguanas are big lizards that they eat in Mexico. There is a big iguana tied up under the veranda of the hotel where the old man and his granddaughter are staying. The Mexicans do this to fatten up the iguanas before they eat it. Every night the iguana creates an annoying noise by scratching at the door all night. There is a tour group from America also staying at the hotel. The tour guide has had sex with a teenage girl in the tour group, and because this is a crime in America, he can’t go back there. YM: So, this iguana is tied up and eventually gets eaten? Is the iguana some kind of symbol? TW: Yes. But it’s not a symbol of any one character in particular. The iguana is a symbol of each and every character in the play. Do you see that? In other words, none of them can run away. The only one that escapes is the iguana. That is because the granddaughter finally releases the iguana from the natives who have tied it up. This is the end of the play. The woman appears on the porch. Behind her, although she can’t see it, the old man has another stroke and dies. What is important here is that the old man has actually not written any poetry for many years, but he has had one unfinished poem and this very night he completes it. But his granddaughter doesn’t know the old man has died and she says, “It’s so quiet here, now.” This is the last line of the play. YM: That sounds really interesting. Didn’t you write a novel with the same title, “Night of the Iguana”? FM: There is a short story, but the only thing they have in common is the title and the iguana. Other than that, everything in the play is new. YM: I’m thinking about a new play too, this is about a love suicide of a brother and sister. TW: Now that sounds interesting! Is it long? Short? YM: It’s long. I’m writing it for a Shingeki modern theater troupe. TW: I’d like someone to make me a literal translation and then I could turn it into a proper play in English. I think that would be great! 7. The Life of a Playwright FM: Mr. Mishima, how do you work? Richie: He usually works through the night. Then he sleeps until about one or two in the afternoon. He works like this every day for about a month, then he takes it easy for a month. TW: That sounds ideal! I get up every morning at seven, or even earlier, and write. Richie: Do you do that even when you are out of America? Are you doing that now? TW: Yes. Wherever I go, I always work. While I’ve been in Japan, I’ve been writing every morning. As you well know, writing is not pleasant. You work and work and work and it feels like you are pounding your fists on a stone wall and it is very physically demanding. That is why after stopping work, I am irritable for the rest of the day. Richie: But there must be some times when the writing comes easily? TW: Yes, occasionally that happens. That is when the real creation takes place. That’s when you can really write something good. It takes me about a year and a half to write one play, but during that time, the amount of time that I actually can write is only about five days. The rest of that time is preparing to write what I write in those five days. When those five days come, it is like a dam has burst and everything comes pouring out. Then I finish it all at one go. But the other days are continual painful effort. That is why I am always exhausted. An artist is like a person who chews away his own skin. Every day you cut your own veins and every day you expose all your nerves. That’s why I end up so exhausted.

YM: What about the production?

Courtesy Tennessee Williams Key West Exhibit.