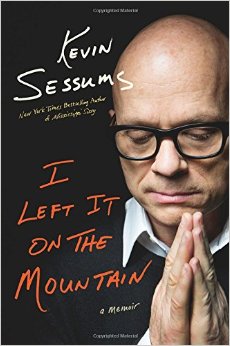

I Left It on the Mountain: A Memoir

I Left It on the Mountain: A Memoir

by Kevin Sessums

St. Martin’s Press. 272 pages, $25.99

“HAVE YOU fucked the angel?” asks Hugh Jackman in the opening chapter of Kevin Sessums’ I Left It on the Mountain: A Memoir, posing the book’s central dilemma: “how to combine the carnal and spiritual.” The question arises during a magazine interview with the Australian actor in L.A.’s Peninsula Hotel, after Sessums shares that since deciding to trek the Camino de Santiago, a 2,000-year-old pilgrimage in northern Spain, he has noticed “all these heightened coincidences,” including a chance encounter at Starbuck’s with the most beautiful boy he’d ever seen—“his blond wavy hair seemed to be encircled by a halo”—who tapped the writer on the shoulder, said he had walked the path the previous year, and handed over his contact information, which included the surname Amore. “An angel called Love,” Sessums tells the movie star.

The Jackman scene is just the first in a series of juxtapositions featuring celebrity hobnobbing, drug-fueled sexcapades, and finally a fitful search for sobriety in the life of the former executive editor for Andy Warhol’s Interview. Sessums, who was also a contributor for Tina Brown at Vanity Fair, made a name for himself getting the glitterati to share their secrets. But make no mistake: I Left It on the Mountain is hardly a tell-all book about the rich and famous.

In his 2007 bestselling coming-of-age memoir, Mississippi Sissy, Sessums recounts tales of woe as an effete, gay orphan in the South, including the death of his father in an automobile accident, that of his mother from cancer when he was eight, and his molestation by a minister when he was thirteen. In this, his second memoir, the journalist describes his very adult life in unflinching detail: a descent into an unmanageable crystal meth addiction accompanied by vacuous sexual hookups, as well as a painful journey to recovery.

At a time when a myriad of books are coming out about celebrity, addiction, and self-healing journeys, Sessums manages to surprise the reader by combining elements of all three genres and holding them together with well-honed prose, thoughtful self-reflection, and a layer of authentic humility. Organized according to his various roles in his world, the book begins with a chapter called “The Starfucker,” in which Sessums describes his interviews and subsequent interactions with Madonna, Jessica Lange, and Courtney Love, a trio he calls his “three blond muses.” Interludes are also included about male talents, such as Tom Cruise, Michael J. Fox, and the aforementioned Hugh Jackman.

Next comes “The Climber,” a chapter in which Sessums describes his climb up Mount Kilimanjaro in search of the self-forgiveness he craved after seroconverting due to drug use. In one particularly poignant moment, a guide shows him the masare, or “Forgiveness Plant,” which is given among family and neighbors in Tanzania as a symbol that all is absolved. Sessums bends to take a cutting as a gift to himself and hears the voice of his dead father. “Son, there’s nothing to forgive.” Sessums leaves the plant untouched. “I left it on the mountain,” he writes, giving the book its title.

Subsequent chapters include: “The Role-Player,” where Sessums realizes that he is an “overaged urchin”—not Daniel Radcliffe, whom he has just interviewed, nor the needy young man from the previous night’s tryst; “The Brother,” which expounds on the author’s relationship with his religiously conservative obstetrician sibling; “The Mentor,” about his first social gurus in New York City—Henry Geldzahler, New York City’s commissioner of cultural affairs and New Yorker poetry editor Howard Moss—plus a delineation of his service mentoring a six-year-old Puerto Rican boy from Brooklyn named Brandon.

But the heart of the book starts with “The Pilgrim,” the tale of Sessums’ walk along the Camino de Santiago de Compostela, on which he embarks in order to abstain from recreational drugs for at least a month and to get back in touch with his spirituality. A noteworthy moment happens on his third night, when an “odd, rather disheveled man” with long hair and wearing a brown sackcloth tunic, approaches Sessums, saying, “I am here to tell you that both your Father and your father are here to guide you on your Camino.” When Sessums queries the desk clerk at his hostel about the stranger, he is told he encountered a fantasma inquietante, a haunting, known as the “angel of Roncesvalles.”

It’s in the final chapter that Sessums brings his story to a crescendo. After staying “mostly drug-free” during the six months after his pilgrimage on the Camino, Sessums has a meth- and sex-filled romp before he has to interview Diane Sawyer the next morning. “Are you sure you’re feeling okay?” the news anchor asks him.

After a days-long bender later that year, on July 4, 2010, Sessums shoots up crystal meth for the first time. What follows are five paragraphs of a truly horrific description of a drug high, shocking for both its brutality and the beauty of its prose. The author enters a new phase in his addiction: hallucinations. He believes that methamphetamines opened a “spiritual portal of some kind” that Lucifer, the “Angel of Light,” and his minions used to conjure themselves in a form of seduction.

These passages are difficult to read, but they shed a poetic light onto the misery of addiction, which the author comes to believe is “the proxy battle for the soul.” Sessums finally discovers a way to blend his sexual and higher natures, finding recovery and with it a greater understanding of the nature of the world: “I know now it wasn’t the angel this whole time I’d been looking to fuck, but the devil I’d been learning to love.

Court Stroud works in Spanish-language media and lives in New York City with his husband, comic Eddie Sarfaty, and their two cats.