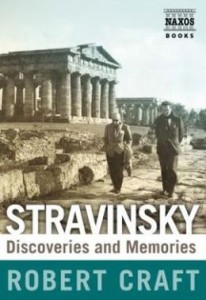

Stravinsky: Discoveries and Memories

Stravinsky: Discoveries and Memories

by Robert Craft

Naxos Books. 360 pages, $34.98

THIS BOOK of disparate recollections and commentaries assembled by the music conductor, critic, and biographer Robert Craft concludes with a list of his two dozen previously published works, only one of which I’d read before. That was the 1972 Stravinsky: Chronicle of a Friendship, a sort of diary recounting the performances, travels, and social life that Craft witnessed and shared with his mentor and friend. I remember being dazzled by the level of culture and sophistication presented in it, along with the catalogue of famous figures Stravinsky and his wife Vera regularly met.

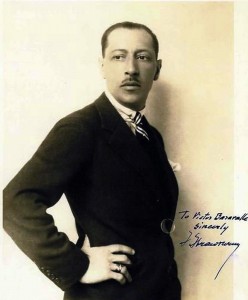

Because Craft was the composer’s disciple and constant companion, he too gained entrée to these glittering occasions, even though some of Stravinsky’s hosts didn’t quite know who he was or why the two seemed to be inseparable. The shortest answer is that as soon as they met in 1948, the great composer realized that this much younger man had an unrivaled knowledge of and devotion to his works, plus an eagerness to assist him in every way possible. The life of a world-famous artist is lonely—also, a logistical headache. So, fairly soon after they became acquainted, Craft was put on the payroll. Just how literal I’m being here, I don’t know. Craft doesn’t discuss his finances, but, constantly traveling and only occasionally working as a maestro, he can’t have earned much money on his own. It must be that someone else was footing the bills. The list of Craft’s published books is long, the majority of them having to do with Stravinsky. I suppose royalties brought in some pocket money, but surely not enough to support the international train de vie those books attest to. The next dossier that Craft opens has to do with Stravinsky’s relationship with the Belgian composer Maurice Charles Delage, to whom Ravel had introduced him. It isn’t yet proved absolutely that Ravel was homosexual, but certainly Delage was. He seems to have been at the center of a very active gay circle. Here is how Craft sums up the situation: “In the spring of 1911 Stravinsky had spent a three-week vacation at Delage’s gay agapemone near Paris, not alone but with the notoriously homosexual Prince Argutinsky, whose letters are still in private hands. A Russian gentleman who has read this correspondence told me a few months after Stravinsky’s death that Argutinsky’s letters are ‘very compromising to Stravinsky biography.’ In the late summer of 1911 Stravinsky sent to Delage from Ustilug a photograph of himself in the nude with a prominent upwardly mobile snozzle.” None of these hearsay assertions is documented, so those who prefer to think of Stravinsky as that rare being, a man who is 100 percent heterosexual, may still be allowed to believe it, at least for a few more years. It could be called caviling, but I find myself disliking terms like “notoriously homosexual,” “compromising,” and “upwardly mobile snozzle.” In the 21st century, being gay doesn’t automatically guarantee “compromising” notoriety; and surely by now we can mention an erect penis without resorting to a sniggering paraphrase. Craft cites a letter from Stravinsky to Delage that does indeed sound very loving, though an obstinate reader could argue that the content was merely affectionate. But there’s more. Craft also believes that Stravinsky and Ravel were off-and-on lovers, instancing a night when the two are on record as having slept together in a single bed. He says that Stravinsky, asked at some later point if it had been a good experience, replied, “You will have to ask Ravel.” Again, the source of the anecdote isn’t documented, so a professional biographer would necessarily challenge it. What can’t be denied is that sex was high among Stravinsky’s priorities, a character trait that led to extramarital affairs with a considerable number of women. This hardly sets him apart from celebrated artists in general, who (as modern biography has many times demonstrated) tend not to place much value on monogamy. “Getting it on the side” is close now to being a ho-hum topic. For me, the value of this book doesn’t, finally, rest on its revelations about Stravinsky’s sexual omnivorousness but instead on the chapters dealing with the master’s professional colleagues and friends. When Craft traces the ups and downs of the Stravinsky-Schoenberg relationship, he is particularly good. As with the earlier Chronicle of a Friendship, I was overtaken by the suspicion that Craft’s deepest admiration is reserved for Schoenberg’s music, with Stravinsky’s coming in second. It’s an opinion he’s entitled to, but you have to ask yourself why he attached himself as an amanuensis to the one and not the other—attached in a manner that some have described as parasitic. The obvious explanation is that Schoenberg never asked him to come on board. Maybe, if the great Viennese innovator had known how much tireless promotion he could have counted on from Craft, he would have signed him up; but then he never earned as much money as Stravinsky, nor lived as long. Alfred Corn’s most recent volume of poems, Tables (Press 53), came out last January. A new volume, titled Unions (Barrow Street), is scheduled for this coming spring. Stravinsky was married and Craft is heterosexual, so it may seem that this book lacks interest for GLBT readers unless they happen to be fans of 20th-century concert music. However, at least one of its chapters ( “Amorous Augmentations”) touches on the question of Stravinsky’s sexual orientation. Though primarily heterosexual, Stravinsky was close to several gay men, Diaghilev in particular, and, according to the author, had actual affairs with one or two. The case Craft makes begins with a summary of the composer’s early infatuation with Andrey Rimsky-Korsakov (Nikolai’s son), a classmate at the University of St. Petersburg. In letters to the young man Stravinsky describes his feelings as “love,” but this seems more like the male bonding described by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick in her study of 19th-century friendship: what we now called “bromance.” In any case, the relationship was derailed when Andrey began attacking The Firebird and The Rite of Spring in print, no doubt because he saw these works as a radical departure from and challenge to his father’s music.

Stravinsky was married and Craft is heterosexual, so it may seem that this book lacks interest for GLBT readers unless they happen to be fans of 20th-century concert music. However, at least one of its chapters ( “Amorous Augmentations”) touches on the question of Stravinsky’s sexual orientation. Though primarily heterosexual, Stravinsky was close to several gay men, Diaghilev in particular, and, according to the author, had actual affairs with one or two. The case Craft makes begins with a summary of the composer’s early infatuation with Andrey Rimsky-Korsakov (Nikolai’s son), a classmate at the University of St. Petersburg. In letters to the young man Stravinsky describes his feelings as “love,” but this seems more like the male bonding described by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick in her study of 19th-century friendship: what we now called “bromance.” In any case, the relationship was derailed when Andrey began attacking The Firebird and The Rite of Spring in print, no doubt because he saw these works as a radical departure from and challenge to his father’s music.