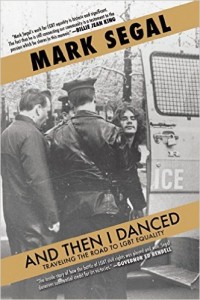

And Then I Danced: Traveling

And Then I Danced: Traveling

the Road to LGBT Equality

by Mark Segal

Akashic Books. 400 pages, $16.95

A GAY MAN refers to his husband, and the conversation doesn’t skip a beat. The New York Times carries so many LGBT-related articles that I think I’m reading a community newspaper. A lesbian, Ellen DeGeneres, and a gay man, Neil Patrick Harris, host Hollywood’s Oscar Awards. In his inaugural address, President Obama makes positive reference to Stonewall, the most important event in modern LGBT history.

For baby boomers and those older, we see all this and think, “How did we get here?” Millennials are more likely to ask, “Wasn’t it always this way?” Both responses highlight the importance of sketching out the history of the last fifty years. How did we move from the 1950s and ’60s, the decades rightly considered the worst time to be queer, to the present, when at least some versions of not-heterosexual are widely visible and accepted?

While deeply researched histories are one way to answer this question, memoir is another. Mark Segal, whose activist career stretches back to Stonewall, is well positioned to recount his decades of making change because much of his activism had its base in Philadelphia Gay News, where he was editor, publisher, and also writer of more columns and stories than one can count.

And Then I Danced begins with a brief account of Segal’s years growing up on the margins in the housing projects of Philadelphia. After graduating high school in 1969, he escaped to New York to find a gay life. That search placed him at the Stonewall Inn the night of the infamous police raid. The experience thrust Segal into the radical world of the Gay Liberation Front, which changed his life forever. When he returned to Philadelphia in the early 1970s for family reasons, he was committed to a life of activism. Fortunately, his family accepted both his identity and his activism, and in the 1970s he remained on the leading edge of the gay and lesbian movement. A founder and prime mover of the Gay Raiders, which organized disruptive protests of public figures known as “zaps,” Segal focused the group’s energies on the media as a route to gaining visibility. Popular television figures such as Mike Douglas and Johnny Carson were targets. But the Raiders achieved national notoriety in late 1973 when Segal ran across the set of the CBS Evening News, hosted by America’s most beloved anchor, Walter Cronkite, to protest the show’s inattention to gay issues. His action stopped the show for a few seconds, achieved national headlines, and initiated a relationship with Cronkite that led to changes in coverage of the movement.

These successes brought home to Segal the importance of the media for creating a sustained voice in the world of news and politics. In the mid-’70s, he shifted track and founded Philadelphia Gay News, which is still being published today. For Segal, journalism was not about “objective” or dispassionate reporting. It was another form of advocacy. The paper provided a platform from which to influence local and state politics. He went after politicians in print—city council members, mayors, governors, and candidates aspiring to office—and then, when his attacks caught their attention, happily worked with them on proposals for change. Decades of such activist journalism led Segal to perhaps the best sound bite in this memoir: “Change does not happen without working the system. … You have to be in the game to win it.”

And win it Segal does, at least at the level of personal stature. By the early 21st century he was on speaking terms with just about every statewide and Philadelphia-centered political figure, and he was intimate with many. He organized a benefit concert featuring Elton John and flew to Europe to meet the legendary singer. Then, as his memoir comes to its close, he and his husband are dancing at a White House reception. Segal has traveled a long distance indeed from the boy in the projects in Philadelphia.

And win it Segal does, at least at the level of personal stature. By the early 21st century he was on speaking terms with just about every statewide and Philadelphia-centered political figure, and he was intimate with many. He organized a benefit concert featuring Elton John and flew to Europe to meet the legendary singer. Then, as his memoir comes to its close, he and his husband are dancing at a White House reception. Segal has traveled a long distance indeed from the boy in the projects in Philadelphia.

How did he, and the larger movement, accomplish all of this? Segal makes clear the personal dimensions of this achievement in the way he describes himself. He speaks of his “dogged determination” and “shameless” style of putting himself out there. Throughout the memoir he describes himself as taking an in-your-face, don’t-mess-with-me stance that politicians knew could not be stopped by dismissing him. You ignore Mark Segal at your own risk.

While this personality made for many successful activist interventions, it works less well on the printed page. Segal certainly has gripping tales to tell, especially in the earlier chapters of the memoir. But as the decades move forward and his stature rises, he seems obsessed with singing his own praises. Over and over, he tells us that he was “the first media person” to do something, or that “nothing of this magnitude” had ever occurred before, or that he had achieved yet “another national first.” It wore on me after a while. Worse, it seems to lead him to make some odd choices about what to include. The AIDS pandemic of the 1980s hardly figures in this memoir of activism. Was it perhaps not an era when he could take big victory laps? But organizing an Elton John concert? He devotes more pages to this than to any other topic or campaign, perhaps so we can see him shining in the gleam of the singer’s global celebrity.

The political implications of the narrative arc also left me puzzled. Segal writes with gusto about the “revolutionary” stance of the Gay Liberation Front and its activists. It is radicals who made things happen, he lets us know. But by the end, he is not only working the system and basking in the light of celebrities and politicians (including Republicans), but exuberantly praising the Human Rights Campaign for all the good work it has done over the decades. Is Segal intending to say that, in this age of marriage, concerts, and White House receptions, the need for radical activism is over? Has the revolution been accomplished? Is the HRC our future?

It is impossible to read Segal’s account and not come face-to-face with the reality that change has indeed occurred over the last five decades—monumental change that was once unimaginable. We ought to be pleased about the victories. But the changes he describes and helped provoke have occurred over the same decades in which the U.S. has become more politically conservative than at any time in the last century. Yes, there have been huge gains for some LGBT people. But deep inequality is the name of the game these days, including for many gay people. That being the case, maybe the lesson of And Then I Danced is that we need more of the radical, outsider, challenge-the-system activism that once animated Segal but now seems lost to him in an excess of self-satisfaction.

John D’Emilio’s latest book is In a New Century: Essays on Queer History, Politics, and Community Life (2014).