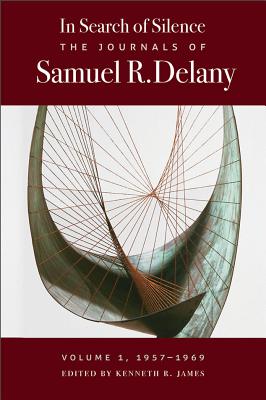

In Search of Silence: The Journals of

In Search of Silence: The Journals of

Samuel R. Delany, Volume 1, 1957-1969

Edited by Kenneth R. James

Wesleyan. 720 pages, $40.

FOR THOSE OF US who grew up reading Samuel Delany’s science fiction novels or who benefited from his exceptionally detailed books on the craft of writing, there are so many mouthwatering bits in this volume, his first twelve years of journals, that it’s hard to know where to jump in. For those less familiar with Delany’s career, a good starting point might be that he was born in 1942 and started keeping a journal at a young age. The entries in In Search of Silence begin when he was fifteen years old.

His youth is not at all obvious from the quality of the writing, which could be that of a graduate student in literature. At sixteen he writes: “I must stop being so analytical when I read; and be more so when I write. I have lost more effect from the greatest works of literature than anybody in the world—I bet. That’s it! I’m too chemical. I know too much about what is being done with the words and themes. Although I can whip the words into place myself, I can see the scars on the backs of the words whipped by other writers.” One unusual aspect of these journals is that here and there Delany has entered the words of his wife during part of this period, the poet Marilyn Hacker, whose comments are often as snarky as they are perceptive: I know a young man called Delany Hacker and Delany were married for several years and had a daughter, but both were always rather free-floating in their sexuality. Today, Hacker identifies as lesbian and Delany as gay. Mixed in with a wide variety of plot ideas and miniature stories are aphorisms that stand out from the page, such as this one: “Since Lord Byron, most art has been constructed so that the audience identifies with the myth of the artist rather than the body of the artist’s work.” That may actually be true of Delany himself, having become something of an icon in the urban literary universe. Early on, however, he was more like a factory, and his output was staggering. By age 26 he had published nine science fiction novels, including Babel-17 and The Einstein Intersection, both of which won the Nebula Award as best novel of the year from the Science Fiction Writers of America. One fascinating aspect of the journals is that they contain all manner of early scene-setting, character ideas, and other brainstorming for his stories. There are also delightful ditties about people he knew in New York City in his youth, such as this sly commentary on W. H. Auden and his partner, the more promiscuous Chester Kallman: Delany had a well-developed concept of how his preferred genre, science fiction (SF), differed from “mainstream” literature: “SF is the literature that posits man is changing. Mainstream is the literature that posits he cannot change. Science fiction is the only heroic fiction left today; it’s the only fiction today that admits there is a solution to its problems. Mainstream fiction is like looking in a mirror. SF is like looking through a door.” One interesting aspect of the journals is that Delany’s science fiction plots, characters, and ideas are remarkably varied and original, while his sexual fantasy vignettes are pretty much variations on a theme: young black man meets rough blue-collar white cracker and sucks him off, often with one or both parties peeing. Such, perhaps, is the focused nature of sexual desire, however vast the possibilities of technology and human adaptation in the writer’s imagined worlds. Alan Contreras is a writer and education consultant living in Eugene, Oregon. By the time he was in high school, his erudition was absurdly advanced, as was his reading list. What stands out even at that age is the fearlessness of his writing and his choice of subjects. Even then he saw extraordinary things that other people simply did not. Items that found their way into his journals might include descriptions of fantasized casual sex on subway cars, in farm-boy trucks, or on backwoods porches. Also present are little asides that spice up the flow of ideas and plot summaries: “They say that Homer was a blind man led by a young boy. I don’t know about you, but when I was a young boy, I was warned to stay away from strange old men.” Or this little gem: “For poetry I say to the unwary/ Is passion with a dash of dictionary.” It didn’t take long for Delany to decide that he wasn’t a young boy anymore: he was vigorously and variably sexual by his late teens and has stayed that way ever since.

By the time he was in high school, his erudition was absurdly advanced, as was his reading list. What stands out even at that age is the fearlessness of his writing and his choice of subjects. Even then he saw extraordinary things that other people simply did not. Items that found their way into his journals might include descriptions of fantasized casual sex on subway cars, in farm-boy trucks, or on backwoods porches. Also present are little asides that spice up the flow of ideas and plot summaries: “They say that Homer was a blind man led by a young boy. I don’t know about you, but when I was a young boy, I was warned to stay away from strange old men.” Or this little gem: “For poetry I say to the unwary/ Is passion with a dash of dictionary.” It didn’t take long for Delany to decide that he wasn’t a young boy anymore: he was vigorously and variably sexual by his late teens and has stayed that way ever since.

Whose verse isn’t overly brainy

When you start to get with him

He completely drops the concept of rhythm

And eventually doesn’t bother rhyming, either

Which would be all right if

He didn’t start out

With it.

“Where are you going,” said Wystan to Chester

“The boys in the park are a very bad lot.

The sore on your cock is beginning to fester

And what can they give you—that I haven’t got.”