WONDROUS TRANSFORMATIONS

WONDROUS TRANSFORMATIONS

A Maverick Physician, the Science of

Hormones, and the Birth of the Transgender Revolution

by Alison Li

University of North Carolina Press

258 pages, $30.

“TO DEAR HARRY, Such a grand time we had in San Francisco. Fondly, Chris.” Christine Jorgensen’s autographed glossy photograph reveals her enduring friendship with Dr. Harry Benjamin. Jorgensen, of course, was the Danish-American former GI who had sought medical treatment in Denmark to achieve hormonal “sex transformation” treatment. After her widely covered return to the U.S. in 1953, she sought out Benjamin for continued medical care in New York. Thanks to the global publicity Jorgensen drew to transsexualism and her association with Benjamin, they fostered the humane medical care of transgender people.

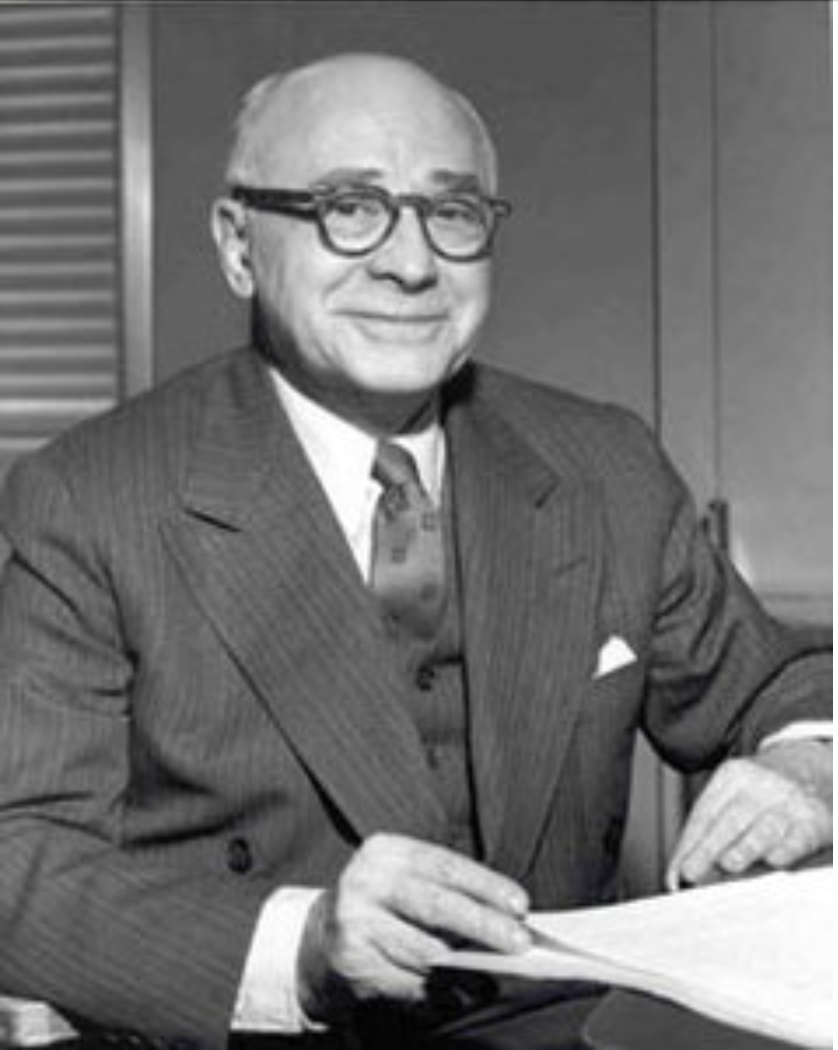

The research foundation that Benjamin founded in 1964 sponsored international symposia on “gender dysphoria.” In 1979 the group was named in his honor as the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association. In 2007 it was renamed the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (to reduce the association with mental illness). However, this development in his career was just the coda to a long and fascinating life (he lived to age 101!). Earlier, he had promoted various experimental, miraculous, and possibly quack treatments for everything from tuberculosis to aging. His involvement with transgender care has been documented within the history of endocrinology or transgender studies by scholars such as Joanne Meyerowitz, Chandak Sengoopta, and Nelly Oudshoorn. However, historians of many disciplines have been eagerly awaiting a more complete biography of this pioneering physician. Allison Li has finally produced this volume.

Harry Benjamin (1885–1986) was born in Berlin. His father’s family were Jews from a small agrarian town in Prussian Brandenburg (now on the border with Poland). His mother was from a middle-class Lutheran family, originally from Westphalia. His father became a prosperous banker, affording Harry a humanistic, classical education in private schools. However, Harry had a rough time fitting in: he was viewed as Jewish by Christian peers and as a Gentile by wealthy Jewish families. Li suggests that this crisis of identity sensitized Benjamin to the distress of marginalized people. His cultured family instilled in him a lifelong appreciation for the arts, especially opera. His sister Edith was a soprano and went on to have a professional career in the U.S. Harry studied medicine in Berlin, Rostock, and Tübingen, interrupted by six months of compulsory military service in1908. Germany was a leader in medicine at the time, and it was common for students to study at multiple universities to gain the best training. His first trip to America was in 1913 as an assistant to Friedrich Franz Friedmann, a flashy doctor who was peddling his “turtle serum.” It was supposedly extracted from turtles and was touted as a miraculous cure for tuberculosis. (The antibiotic streptomycin was not discovered as an effective cure until the 1940s.) Desperate and wealthy Americans pursued the rare turtle treatment. Investors threw money at Friedmann. Benjamin was supposed to gather data to demonstrate the efficacy of the “turtle serum.” He only fully realized it was a scam when Friedmann ran off to Germany with the money, leaving him stranded in the U.S. Nevertheless, Benjamin became interested in the emerging field of endocrinology as various glandular extracts began to be hypothesized and then isolated as part of the complex system of hormonal regulation of the body. He struggled to make ends meet in the U.S. as a young physician with limited English skills. In November of 1913, his father died back in Berlin. He was finally able to afford an ocean liner ticket back to Europe in July of 1914—just as the Great War was breaking out. He became stranded in England but eventually managed to make his way back across the Atlantic to Philadelphia. In 1915, he earned his New York state medical license. Benjamin’s next endocrinological fascination was with the “Steinach operation.” On his return to Europe in 1921, Benjamin met the venerable Viennese physician Eugen Steinach, who had invented and widely promoted this operation to promote “rejuvenation” in men. It consisted in tying off the ducts carrying sperm from the testes to the urethra. The rationale was that this created back pressure on the testes (the “puberty gland”) to produce their “internal secretion”—thus renewing male potency and lengthening life and vitality. It had a certain hydraulic logic, although it would eventually be proven ineffective. Nevertheless, Benjamin believed in it fervently enough that he underwent the procedure himself, as did Sigmund Freud. Other comparable treatments of the time included testicular extracts and testicular implants from monkeys. Similar approaches were also used in the treatment of “sexual inversion” or homosexuality, based on the rationale that effeminate males were deficient in vital testicular secretions, or else their testes were producing defective ones. What we now term the “sex hormones” or sex steroids were first being extracted and identified in the 1920s and ’30s. But calling them “sex hormones” remains an enduring misnomer. Almost as soon as they were discovered, physiologists found that both “male” and “female” hormones are produced across the sexes and are broadly important to health, not just sexual traits. Li tracks how Benjamin, upon returning to the U.S. in the fall of 1921, began promoting the Steinach operation as well as the use of these glandular extracts for “rejuvenation” in men and women. Evincing an entrepreneurial spirit, he and two colleagues formed the Hormone Research Corporation to isolate a male hormone that could be exploited for clinical use. But their lab was beaten to the punch by researchers at the University of Chicago in 1929. Benjamin’s venture into hormone production had collapsed by 1931. It wasn’t until 1935 that three European drug companies (Organon, Ciba, and Schering) simultaneously isolated and synthesized crystalline “testosterone.” The discovery led to a Nobel Prize in 1939. Benjamin adapted the Steinach procedure to women by directing X-ray radiation to the ovaries, which would presumably lead to sterility. One patient who underwent this procedure, author Gertrude Franklin Horn Atherton, believed it boosted her vitality and cured her of her “mental sterility.” Li notes that Benjamin was surprised that the women flocking to his office were not housewives seeking a magical fountain of youth, but instead business owners and professional women. I have to wonder whether many of these women were lesbians, willing to trade fertility and family for the promise of professional achievement. Atherton remained a lifelong friend and promoter of Benjamin’s hormonal treatments (which would have functioned like postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy today). Li mines Benjamin’s correspondence with Atherton and others for fascinating details on his scientific theories, clinical practice, and political views. He established a second practice in San Francisco in 1933, where he also cared for sex workers at two brothels. His medical practice declined during World War II, but he was soon able to recover, running offices in both New York City and San Francisco. He also managed to attend medical conferences in Europe, meeting leaders in sexology with whom he maintained lively correspondences. In this way, through the career of Benjamin, Li provides us with a wonderful survey of 20th-century sexology. Benjamin visited Magnus Hirschfeld at his Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin. He treated patients who’d been referred to him by Alfred Kinsey. His meeting with Freud in 1928 did not go so well. Li notes that after Benjamin confessed to his impotence with his wife, Freud suggested that Benjamin was a “latent homosexual.” Li ruefully admits that we don’t have any firm proof that he was, only scant evidence that “he had a fetish for very thin girls with very long hair.” Li points out how Benjamin was very liberal-minded, which was in keeping with other researchers in the controversial field of sexology. His promotion of new and largely untested medical interventions was not without its critics. He engaged in a war of words and an unsuccessful lawsuit against Morris Fishbein, the editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association. Fishbein’s Medical Follies (1925) had criticized Benjamin’s methods along with other dubious medical practices and devices of the time. Other physicians in the AMA tended to lump Benjamin in with “quacks, near-quacks, and faddists.” Yet, by all the epistolary evidence, he was a warm, beloved physician who cared for his patients with Old World charm and thoroughness. He had already had a long, successful career as a gerontologist and endocrinologist by the time Christine Jorgensen brought him into transgender care in the 1950s. Her global fame drew hundreds of letters of inquiring about transsexual medical treatment; she was able to redirect these to Benjamin. He was the perfect person at the right time. He had certainly been introduced to homosexuals, transvestites, and transsexuals in Berlin through his friendship with Magnus Hirschfeld. Li documents how Benjamin had made his first recommendation for cross-sex hormone therapy in 1949—to a patient referred by Kinsey. Benjamin was uniquely predisposed to understand the plight of transgender people as grounded in biology rather than psychopathology, which was the dominant psychoanalytic model of the time. Thanks to Jorgensen’s referrals and his growing reputation, Benjamin was able to become a leader in the clinical care of transgender people in the 1950s and ’60s. Jorgensen became the medical model for the standard, healthy “transsexual,” and Benjamin became the nexus for other sympathetic clinicians and sexologists. This experience was distilled into his best-known publication, The Transsexual Phenomenon (1966). He simultaneously spearheaded the medicalization and the legitimization of transgender health care. Other medical historians, notably Joanne Meyerowitz in How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality in the United States (2002), have documented Benjamin’s pioneering work in the incredibly productive last third of his life. However, Li provides the much anticipated full appraisal of his many contributions to gerontology, sexology, and endocrinology. Her access to German archival source documents was indispensable to this project. Her meticulous scholarship does not hamper her lively storytelling. While I can have imagined a more politically or theoretically censorious take on Benjamin, it was a relief not to hear any of that shrillness. Ultimately, Alison Li’s biography is as affectionate as Christine Jorgensen’s dedication, representing many years of being engrossed in the life of Harry Benjamin.

Vernon Rosario is a historian of medicine and a UCLA child psychiatrist practicing in the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health.