THE EPICENTER of gay culture lies in Black gay, same-gender-loving, trans, lesbian, bisexual, and queer language. Black gay and queer vernacular has had a major impact on the larger LGBT+ community. The ability to modify and explore the dynamics of language to enhance our idea of an inclusive culture—one that allows freedom of gender and sexual expression—pierces through the heights of creativity. At the root of this language, now woven through mainstream society, there is a deep and complex history of the Black and queer communities. It comes with a shared legacy of hate, racism, discrimination, and oppression engendered by people who faced systematic attacks for being both Black and queer.

Racism and discrimination are at the root of American history. For centuries, Blacks were not allowed in white spaces and, by extension, Black gay people were not welcomed into white gay spaces. Homophobia and transphobia are disproportionately experienced in the Black community, and “BlaQueers” are marginalized and victimized, facing double systematic attacks because of their identities. The cycle of oppression permeates both race and sex. But out of the darkness, something beautiful can arise.

The personification of Black gay and queer language is seen in the countless, fearless leaders in the history of Black LGBT culture. The 1920s Harlem Renaissance was the mecca for Black writers, artists, and musicians, many of whom were prolific in their output. It was the heartbeat of the Black gay experience and the incubator of a vocabulary that was Black and queer. Many historians and researchers, notably Henry Louis Gates, Jr., have noted that it was in fact as gay as it was Black. During the Harlem Renaissance, the coded queer undertones of writers like Richard Bruce Nugent, Wallace Thurman, and Claude McKay describe their experiences with men. There were Black “bull dykes” like bawdy blues diva Ma Rainey in her song “Prove It on Me,” which included the line: “talked to the girls just like any old man.” And there were entertainers such as Gladys Bentley, Florence Mills, and Ethel Waters who dressed in male drag and flaunted their best dapper looks.

Bessie Smith, Alain Locke, Alice Dunbar Nelson, James Weldon Johnson, Countee Collin, and Josephine Baker were all “in the life,” and their queer innuendos have influenced Black LGBT language and culture. Drag balls at the legendary Savoy Ballroom and Hamilton Lodge stood as the signature places where Black queer people gathered. Langston Hughes, who was undoubtedly gay but largely closeted, wrote in his autobiography The Big Sea about these “spectacles of color”: the extravagant Black drag ball affairs that were lavish with the latest fashions, music, and dances. Black bodies were liberated, celebrated, and empowered in their Black and queer identities. Everyone wanted a taste of these masquerade balls, and it didn’t matter if you were gay, straight, white, or Black. Over 3,000 spectators would crowd into a ballroom and marvel at its grandeur.

Marlon Riggs’ 1989 film Tongues Untied, along with the poetry of Essex Hemp-hill, Assotto Saint, and Donald Woods during the radical Black queer era of the AIDS crisis, affirmed the identity of Black gay men and celebrated race, sex, and language. These activists fought to empower their identities and challenged those who would prevent their full expression. In the words of Essex Hemphill in Ceremonies: Prose and Poetry (1992): “This is what the race has depended on in being able to erase homosexuality from our recorded history. The ‘chosen’ history. But sacred constructions of silence are futile exercises in denial. We will not go away with our issues of sexuality. We are coming home.”

Joseph Beam’s anthology In the Life and the explosive Black feminist language of Anita Cornwell’s Black Lesbian in White America documented the ways in which Black lesbians have put their stamp on queer linguistic expression, including Audre Lorde’s proclamation that “women are powerful and dangerous,” and bell hooks’ affirming that she will not bow down before oppressors. The Black lesbian community created “diva femme,” “stemme,” “futch,” “soft stud,” and “AG” to explore the diverse spectrum of identities that exist in lesbian communities. More recent examples, such as Oakland native B. Cole of Brown Boi Project, who popularized the word “boi,” refer to queer identities and expressions that lean towards masculinity. Black gay, same-gender-loving, trans, lesbian, bisexual, and queer language has a deep and rich history and is still continuing to evolve. Its nuances and creativity are bold, daring and brilliant, often causing those not in the community to emulate it.

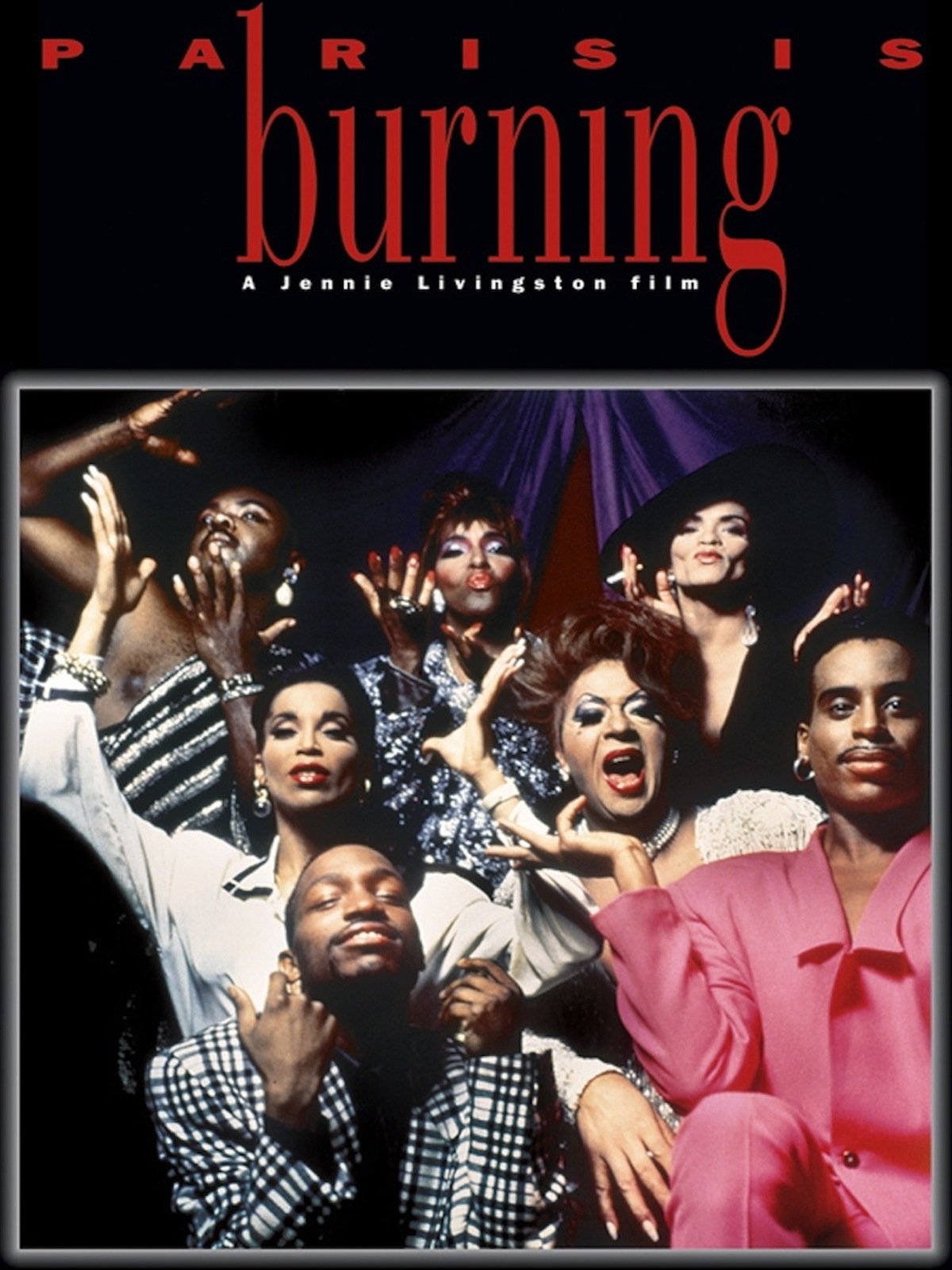

Before Pose, there was the awarding-winning documentary, Paris is Burning (1990), and before director Jennie Livingston decided to document ball culture, the culture was already thriving. The “ballroom scene” or “house culture” is probably one of the hottest trends of both gay and pop culture, and the lingo is “fierce”! “Yaasss!” rings out as if it is the official pop culture anthem. RuPaul’s 1993 mega hit “Supermodel” (“You Better Work”) had even middle-aged white suburbanites saying “work,” and the expressive lexicon sashays from the lips of RuPaul’s Drag Race contestants like a regal queen on the highest throne: “Yaasss, queen! Sissy that walk! Mother is serving realness, children!”

The language of the ballroom scene has exploded into mainstream culture like never before. Everyone loves to “throw shade,” “read,” “vogue,” “dip,” and “slay” all day! Instagram videos of legendary ballroom walker Leiomy “Wonder Woman of Vogue” Maldonado warrant grander comments like “slay,” “werk,” “muva,” and “fierce,” as she devours “hands performance,” “duckwalks” and “dips,” all expressions whose origins come from the ballroom scene.

Gay bars echoed with laughter while friendly greetings of “Hunty” and “Sis, spill the T” would fill the room. On occasion—especially after a drink or two—a “Child, please don’t come for me” or a sly “You shady bitch” might make their entrances. These phrases originated in the ballroom scene and have been appropriated by the larger LGBT+ community and mainstream culture. These expressions are capitalized, monetized, branded on clothing, and heard in the latest music. However, most people don’t realize that these words were brought to life by Crystal LaBeija, Dorian Corey, Paris Dupree, Kim Pendavis, Junior LaBeija, and the countless members of the Houses of Corey, Dior, Wong, Christian, Ebony, Omni (UltraOmni), and the list goes on. These words come from the Black and also Latinx, gay and trans communities, and from the ballroom scene that originated in Harlem.

The extravagant gay drag balls of the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and ’30s re-emerged in the 1970s in a new form. The Harlem ballroom scene was created because the predominantly white gay balls discriminated against the Black and Latinx queens who competed in the pageants. In the documentary The Queen, a highlight of the American drag ball circuit and official 1967 drag pageant competition, drag performer Crystal LaBeija shows her dissatisfaction with the judges’ decision to eliminate the contestants of color and crown a white contestant. Crystal “reads” the producers, commentator, and contestants for this unfair treatment. When she was told that she was “showing her color,” she had a profound “clapback,” saying: “My color is beautiful!” This moment signaled the birth of the new Harlem ballroom scene, which featured Black and Latinx queens who felt marginalized by the predominantly white gay balls.

These highly energized balls featured categories in which Black and Latinx people of diverse gender identities and expressions—“butch queens,” “femme queens,” “drag queens,” “butches,” “transmen” and “-women”—could “walk” (compete) for highly coveted prizes, trophies, and titles. House culture was built on “chosen families”—groups that, while not biologically or legally related, had a bond that fulfilled the same purposes as a family unit. These families, or “houses,” were created because Black queer people are often disowned by their biological families. The houses, consisting of a “house mother” and/or “house father,” provided these young people, “the children,” a supportive and nurturing network to live in freely and authentically.

Using the language of Black and Latinx gay and trans ballroom vernacular, pop star Madonna started an international new craze with her chart-topping song, “Vogue.” After visiting the New York underground dance clubs and balls, Madonna took the language and dance of the ballroom scene and made it mainstream. This is only one of the many examples of how ballroom language has been annexed and monetized. Many non-Black members in the queer community and beyond have adopted this language, which describes the unique identities and experiences of the Black community. These words are sometimes used incorrectly, causing the Black queer community to feel a loss of ownership or that their language has been co-opted.

Internationally, popular platforms like RuPaul’s Drag Race, Pose, Legendary, Queer Eye, and celebrities like Madonna, Beyoncé, Lady Gaga, and even Justin Bieber have been instrumental in mainstreaming Black gay and queer language. As a result, large swaths of the population are conversant with the terms “in the life,” “throwing shade,” “read,” and “beat.” But as the lines between mainstream and Black queer culture continue to blur, this trend can strip and silence a community and its history. This appropriation takes the styles and traditions (e.g., Black music, language, fashion, dance, hairstyles) of a marginalized community without permission or even acknowledgment of their origins. Cultural appropriation erases heritage and creates a false interpretation of history. Fans of Madonna or Justin Bieber—or at least those who don’t watch Drag Race or Pose—may have no idea where the language used by their beloved celebrities comes from.

During the Harlem Renaissance, Black lesbians like Ethel Waters, Moms Mabley, and Gladys Bentley coined and popularized the words “bulldagger” and “bulldyke,” which was shortened to “dyke.” These words defined a woman whose appearance and manner were seen as masculine. Over time, “bull dyke” and “dyke” found their way into mainstream usage, where they were used as derogatory slurs toward gay women. As Black gay and queer language reemerges today for a new generation and becomes part of mainstream culture, phrases like “Spill the T”—to deliver news or gossip—are sometimes misused and misinterpreted. Pop culture has taken this particular idiom and created memes and animated graphics using a cup of tea, not understanding that the “T” stands for truth. Actors on the hit reality series Real Housewives sometimes use the expression so carelessly that eventually its original meaning and etymology are lost.

Black vernacular in general, which consists of words, expressions, and tonality, is created to articulate the unique experiences of Black people and culture. This language is deployed for survival, protection, and affirmation. The expressions of the Black gay and queer community similarly reflect a nuanced linguistic code that’s not available in standard English.

We must recognize the problem of cultural appropriation. Deeper dialogue is imperative around the fact that Blackness, in all its forms and for a myriad of reasons, is the definition of “cool” in America and has been for at least a century. From “hipster” and “jive” in the 1920s to the notorious The White Negro of Norman Mailer in the ’60s, from jazz to rock ’n’ roll, rap, and hip hop, Black coolness has been commodified, objectified, and commercialized.

We live in a racist system of oppression with a history of silencing and disenfranchising Black people, especially LGBT+ people and communities. But despite the darkness, and in part because of it, something beautiful came out of it: Black culture and art, thought, language, and identity. The Black gay and queer community has been at the vanguard of language creation in America since the beginning of the 20th century. The influence of linguistic expressions from the Harlem Renaissance, Black Feminists, Black radical AIDS activists, the drag scene, gay men, lesbians, transwomen and -men, the nonbinary, and so on, has been extraordinary.

Chloe O. Davis, author of The Queen’s English: The LGBTQIA+ Dictionary of Lingo and Colloquial Phrases, works in the New York entertainment industry.

Discussion1 Comment

Very powerful piece. Thanks for sharing on the ball scene. I’ll check out your book.