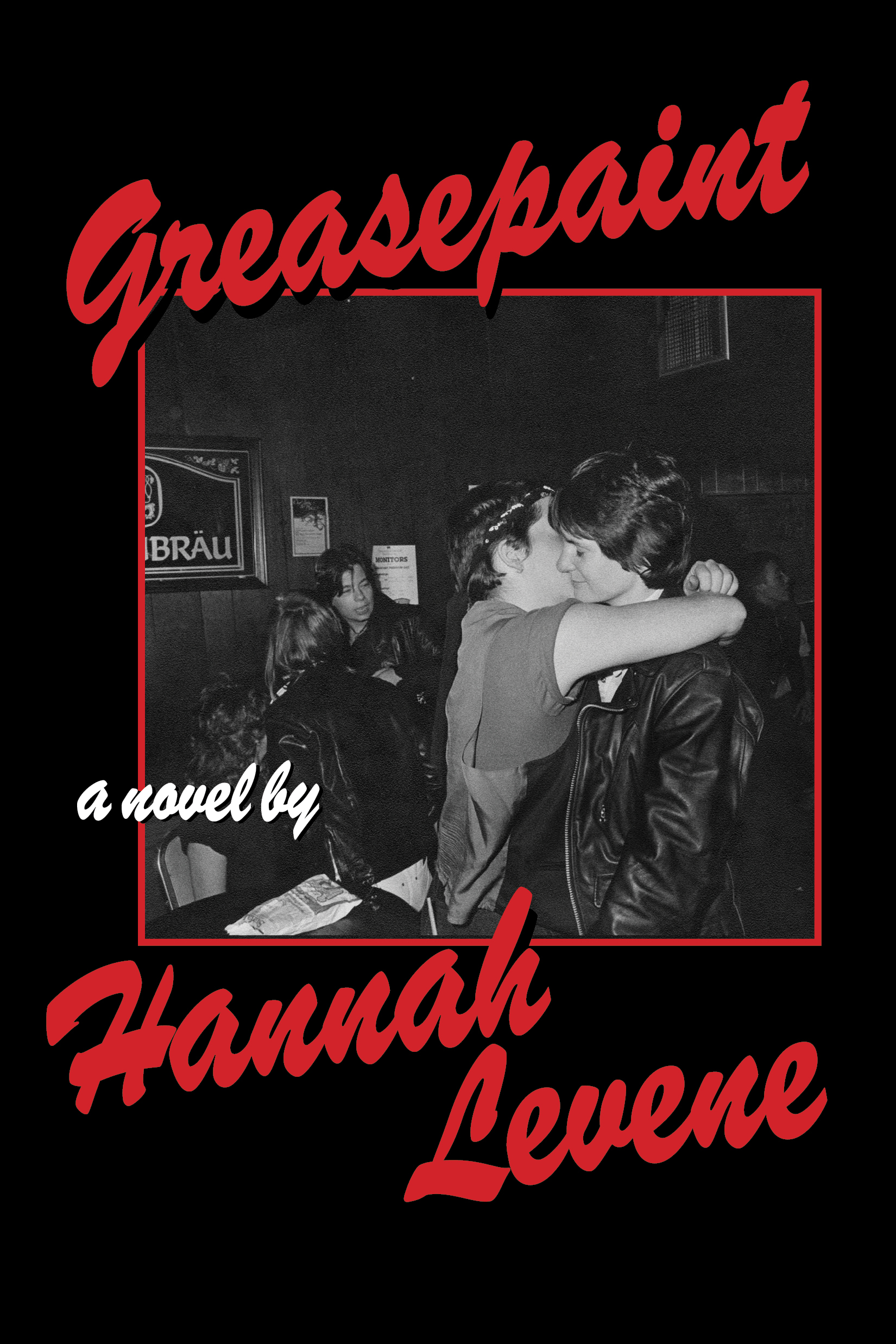

GREASEPAINT: A Novel

GREASEPAINT: A Novel

by Hannah Levene

Nightboat Books, $17.95

“OH BABY it’s another night at Louis’ place” in Hannah Levene’s debut novel Greasepaint, where the Butch on Piano (BOP) faction has important matters to discuss. Louis Brooks calls the meeting to order, reminding everyone of “shake,” “RATTLE,” and “ROLL”—the BOP’s three main characteristics of revolutionary worldbuilding. Harry, the butch who “made the girls melt like tears into a pillow,” strolls in late. But to Sammy Silver, editor of the anarchist newspaper they have gathered to discuss, Harry is right on time. They have to go over her interview in the upcoming newsletter about a Porgy and Bess production touring in Leningrad that includes a discussion of what it means to collaborate on art as a Black American. After that, they’ll play music and smoke and hide from their exes—a typical Friday night for butch dykes and Jewish anarchists in 1950s New York.

Levene uses an ensemble cast of characters, including the Anarchists, the All-Americans, and the BOP, to immerse the reader in the butch-femme bar scene, one similar to that of Leslie Feinberg’s Stone Butch Blues. Rather than a linear plot to move the story forward, the narrative is more impulsive, less conventional, with unanticipated shifts in the tone and topic of the conversation. With this experimental structure, intimate conversations between characters are placed alongside song lyrics and quotations from newspaper interviews and outside texts, creating a patchwork of oral and written history that mimics the rhythm of the improvisational jazz they perform onstage.

This flexibility also creates space for more nuanced conversations about identity at a time when both anarchism and homosexuality were against the law: “The butch is an anarchist and her slacks are stuffed with dynamite,” Levene writes of Sid Stein, a cigarette-smoking dyke who’s been arrested twice for wearing slacks. Other characters include Frankie and her childhood sweetheart Lily, with whom Frankie maintains an on again, off again relationship throughout the novel. In one of their tiffs about whether or not Frankie loves Lily, Frankie says: “I didn’t stay to be a fucking anarchist I stayed to be a fucking dyke, Lily, to be by you so I could feel like a man like a boy for you, that’s why I stayed I could be an anarchist anywhere,” casting a light on the conflict between personal and political identity that’s a recurring theme throughout. Their conversations also highlight tensions between political and gender identities, creating possibilities for gender queerness in a world where the term “nonbinary” isn’t yet widely used: “It didn’t make sense to call Teddy a she so no one did, not cashiers or bartenders, not even his boss.”

On a craft level, Levene uses outside texts, such as The Persistent Desire: A Femme-Butch Reader and Tevye’s Daughters, to challenge the boundary between the real and the imagined for her characters, reanimating an archive of butch history that both reflects and extends the possibilities of queer life at a time when such expressions were stifled, politically and socially. She personifies time: “Time adjusted the knot in its tie and sat up straight again.” This can be read as an homage to Edward Muñoz’s concept of queer futurity, or the idea that queerness is a future-oriented phenomenon, something that in Levene’s setting of 1950s New York brings the past into the future.

As with most experimental novels, the form becomes more accessible over time. The learning curve is all about distinguishing song lyrics from characters’ thoughts and actions while keeping a close eye on the time—in the evening, but also in longer cycles, as flashbacks are used throughout to reveal the story behind characters’ relationships. Levene handles the large cast of characters well, highlighting their separate connections to lesbianism, anarchy, and masculinity. Without shying away from the ways political and racial privilege impact identity within queer spaces, Greasepaint explores the timeless possibilities of butch identity and anarchism, a volatile and symbiotic relationship.

_______________________________________________________

Allison Armijo, the web editor for this magazine, is a creative writing student at Emerson College in Boston.