JIMMY WRIGHT is a successful and acclaimed artist who lives and works in New York City. He and I met almost sixty years ago when we were both contending with the leftover dregs of the 1950s and the fatuity of the second-rate Kentucky teacher’s college where we’d ended up. The unrelenting pressure of those Cold War times, the vapid tyranny of that red dirt abecedary, and the oppression of their combined agendas kept trying to undermine us. We were draft age and the evil American god of war had us in its sights. We both still had the Jesus monkey on our backs, were awash in our deeply repressed outlaw queerness, and always harbored anarchic schemes on our neural back burners. An inscrutable future was impending. All the harbingers were inauspicious. Things looked bleak because they were.

After two preliminary years, Jimmy—I will refer to him by his first name given my personal connection to him—transferred from that Bluegrass backwater to the Art Institute of Chicago, from which he graduated with an honors degree. After taking an MFA at Southern Illinois University, he packed his battered suitcase and headed to New York City.

Starry-eyed artists and writers from flyover states gravitate to New York looking for fame; but not Jimmy Wright. He had come to immerse himself in the newly budding gay culture and find out what it had to show him. The all-embracing ubiquity of New York City being what it was and is, that oracular show-and-tell would be providential both in its bounty and in the impressions inspired by its infinite variety. Jimmy was eager to explore the harlequin mosaic of queer diversity. He had all the skills necessary to turn those impressions into art. Jimmy Wright was born an artist.

Jimmy was always called Jimmy. Growing up on a farm in Western Kentucky, a boy learns many things: how to catch, clean, and cook a fish, where milk comes from, and even how to turn a hog into pork chops. In the country there are a million things you get to know and collect. By the time he started grade school, Jimmy had already assembled an impressive collection of pencils, pens, crayons (the box of sixty-four), watercolors, and hopscotch chalks. In the fall, winter, and spring his focus was the art class at school where he was learning to draw and paint, and during the overheated summer it was all about skinny-dipping in the creek like Huckleberry Finn.

Folks in rural Kentucky know where they came from, who their near relations are, and how the pecking order works. It doesn’t take long for a country boy to find out what’s expected of him and which church pew he’s supposed to occupy on Sunday. If the family pew happens to be vacant some Sunday morning, church ladies are very likely to come calling. When expectations are conciliated you receive modest praise at home, good grades for your drawing efforts at school, and a pat on the head by the preacher after church. These are things that help you get by. And, learning to artfully conciliate the estimations of the always suspicious church ladies means you’re starting to flex your testosterone.

Church is fundamental in western Kentucky, the fundamentalist ones in particular, more so than all the competition put together. Jimmy knew that certain relatives had paved the way for him to attend a church college in Tennessee. The preacher had always singled him out for that pat on the head, and when he got older, a firm handshake and maybe even a pat on the back. Jimmy knew the clock was ticking. Since he already had things figured out and had made his own plans, Jimmy dodged artfully.

Jimmy Wright’s upbringing in that colorful and idiosyncratic bluegrass backwater left a lasting impression which he was eventually able to both transcend and make prodigious use of in his early drawings and paintings. When he presented his portfolio of those first works to the department head in the art section at the nearby teacher’s college, Murray State, Jimmy was granted a full scholarship, the second one he’d been awarded. The first one had been for formal bible instruction at the church college in Tennessee. Since Jimmy now had two scholarships to choose from, Old Testament retrospection lost out to a higher calling. Jimmy had made up his mind. He was all about art.

§

After two preliminary years at Murray State, the yellow brick road led Jimmy Wright to the art school of the Art Institute of Chicago and yet another scholarship. Right away he was welcomed into the Chicago Imagist Movement championed by its mentor, the late Ray Yoshida. I visited Jimmy and his pack during his first year in Chicago and got smuggled backstage at the art school with my sketchbook. At the time, I thought I might move to Chicago and join an antiwar SDS chapter, but fortunately that didn’t pan out. Having successfully defeated the plans of the US Army, I was on a mission to help other potential victims do the same.

A year or so later, in the spring of 1968, on my second visit to Chicago, I was accompanied by my army deserter boyfriend Brian, whose streetwise Jersey City machismo and daunting beauty set the artist’s pens and pencils scribbling. Jimmy successfully sweet-talked the ex-paratrooper into posing butt naked for an impromptu drawing session. Brian flexed and Jimmy sketched and I stood guard. All our friends knew that the FBI was looking to arrest Brian and me for any reason they could find. Later that year, Brian finally made it safely to Montréal and freedom. I joined him the following summer in western Canada, where I’ve been ever since. I lost touch with Jimmy Wright for a few decades since we were at opposite edges of the continent.

§

Let me attempt a rough sketch of the highly motivated, corn-fed Kentuckian Jimmy Wright as I knew him in the ’60s and early ’70s. From a distance, the first thing you’d notice was this skinny, geeky, not-tall, pale young farm boy. If your gaydar was engaged, it would be registering an undeniable he’s-one-of-us vibe. If a laugh happened to erupt, you’d call it a cackle. His nasal Kentucky twang was textbook, and from what my ears tell me, it is ongoing. Back in the day, it appeared that everybody liked Jimmy, and he returned the favor. This sociable trait would eventually serve him well in the rough-and-tumble art world of New York City in the ’70s.

At grad school at Southern Illinois University in 1970, Jimmy lost virtually all of his early work in a disastrous studio fire. This hideous setback would have obliterated a less confident mortal, but Jimmy kept his focus and kept producing art, and he received his MFA. He also managed to accomplish one more vitally necessary goal: successfully securing that all-important 4-F draft exemption by out-maneuvering the government thugs who wanted to ship him off to Vietnam to murder people and/or die.

After graduation Jimmy was awarded an SAIC (School of the Art Institute of Chicago) travel fellowship, which would take him overland through Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, and into Nepal and India. Works inspired by that epic trek would be shown later at Corbett vs. Dempsey Gallery in Chicago. On the way east from the Windy City, Jimmy had stopped off in Manhattan, hooked up with a friend who’d moved there, and got invited to go out dancing at the Stonewall Inn. This was before the bar became world famous and when the cops were still busting people for being queer. Jimmy had already experienced the club life and gritty incognito countercultural scenes in Chicago and the generic police-state, anti-gay oppression, but the bar culture he got to sample during that first encounter with New York was an eye-opener. Things appeared to be different in New York.

Aspiring artists and writers who flock from everywhere to New York are looking for whatever it is (fame and fortune?). Only a few will find it. They mostly find each other. They cluster together in tiny rentals, circulate socially, work temporary gigs, make art or write in their spare time (if any), and mostly chase rainbows.

Jimmy’s first apartment in New York wasn’t in a doorman building and it wasn’t in the West Village or the Upper East Side. Not one of his various roommates had timeshares on Fire Island or met friends after work in ritzy Russian bars. During the Arab oil embargo and the financial crisis of the early ’70s, it was a hand-to-mouth existence. Young people were pulling up stakes and leaving in droves, and hanging in there was a challenge that required grit and tenacity. Way-too-close contact with the foibles and domestic habits of roommates one barely knew could keep the tension cranked up and put a damper on one’s ability to find the time to write or paint.

Nevertheless, the Brooklyn neighborhood where Jimmy spent those first two years had its perks. There were cheap delis and bakeries nearby, and there was access to trains rolling to venues in the City: thrift shops and knockoff stores with bargains, Szechuan wontons to sample, and graffiti art everywhere you looked. In fact, Jimmy told me that teenage Jean-Michel Basquiat lived with his father and two sisters in an apartment across the street.

Then there was the post-Stonewall underground queer nightlife of Manhattan. In their fictional and autobiographical works, queer writers like John Rechy, Harold Norse, Samuel R. Delaney, and Edmund White celebrated those fleeting joys and excesses. There are no photos documenting the nightly deliberations at the Anvil, the Mine Shaft, the docks, or “the trucks.” Cameras were never allowed in those venues, and had a voyeur been foolhardy enough to ignite a flashbulb in the pitch dark interior of a truck, he would have been throttled. Those 70s incognito orgy venues were not unlike the speakeasies of Prohibition times, the Harlem “rent parties” of the Depression, or the ubiquitous whorehouses that have always been around. You had to know where to find them, when they were happening, and what password would gain you access.

The fabulists and chroniclers wrote down their various takes on that fleeting scene, but those narratives left much untold. The single most revealing insider glimpses into that emancipated world of gay abandon were produced in the inspiration of the moment by Jimmy Wright. It’s not that he was sitting on the sidelines wrapped in a towel at the Club Baths recording the colorful goings-on in a sketchbook. Jimmy was way too preoccupied in the heat of the moment to make sketches. Like the historical events that Goya witnessed and documented later in his etchings and paintings, Jimmy was busy absorbing everything visually and taking mental notes—when he wasn’t occupied himself, that is.

It wasn’t that there were no other queer artists chronicling things. There had been a few on the margins. But it’s important to remember that before Stonewall (and even after) everything homo was stigmatized as criminal. The most notorious queer artist was Paul Cadmus, whose classically inspired male nudes and erotically satiric “magic realist” paintings of same-sex encounters made some waves. Cadmus, a gifted draftsman, worked mostly from models in the studio. His works were savaged by some critics, ignored by others. They were eventually rehabilitated in a 1986 monograph published by Lincoln Kirstein, and later by Guy Davenport in The Hunter Gracchus.

Harry Bush, a brilliant, self-taught graphic artist also from the previous generation, was definitely a forerunner as well. Bush produced provocative cover art for mid-1960s issues of Bob Miser’s Physique Pictorial and Athletic Model Guild, and through the ’70s he did illustrations for the queer skin mags In Touch, Blueboy, Drummer, and others. Bush worked almost exclusively from photographs in magazines. The boy mags were his primary inspiration, and his renderings took those sleek posed provocations to a lapidary level. His surviving soft-core porn drawings of rowdy teenage hustlers, hitchhikers, lifeguards, fraternity boys, jocks, and military machos were collected in 1994 and published by Green Candy Press in the gorgeous book Hard Boys. Bush came out very late in life. When he retired from his career in the military (he was posted for many years at the Pentagon), he had confided to friends that he’d always worried about being outed and losing his benefits.

Jimmy didn’t join the ranks of the night owl graffiti taggers and street artists whose designs could be seen throughout the city, though he did appreciate their desire to make their temporary art public and respected the democratizing attempt that their gesture implied. The work of two of that nocturnal and mostly anonymous crew, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, has left an indelible mark despite the evanescence of their now vanished public messaging.

Jimmy Wright’s more emphatic queer citations in his New York Underground Show at the Fierman Gallery in 2016 blew the closet door off its hinges. It featured paintings and drawings produced during those first mid-’70s explorations depicting explicit scenes of cruising, tearoom encounters, bathhouse orgies, public sex, bacchanals in “the trucks,” as well as dreamy iconography of fantasy California surfers, disco queens, and urban cowboys. The narrative approaches elaborated in this series of groundbreaking paintings echo insights gained during his Chicago Art Institute years.

Goya appears to have been worried that no one would believe the scenes he had recorded in his stark 1806 “Disasters” series of etchings. On one of them he had scratched “Yo lo vi!” (“I saw it!”). Jimmy Wright didn’t tag any of his New York Underground paintings with a similar testimonial. He may have thought that, with the passage of time, their credibility would be recognized, or, more likely, since queer anything was persona non grata, any thought of future relevance probably wouldn’t have occurred to him. His depiction of a sex scene he had observed at the Anvil in Anvil #1 1975, which is now in the collection of the Whitney Museum, celebrates a glimpse of a bygone pre-AIDS subculture. Jimmy draws and paints from his imagination in a visual language of his own, an approach that “translates form through personal gestures into feelings,” as he put it an interview.

A recent critic referring to that breakout series of historic paintings has compared Jimmy Wright’s documentation to earlier images recorded in his writings and photography by Samuel M. Steward. She referred to them as “a singular pair of secret historians who produced true life portraits of radical homosexual America.”

The marginality of those clandestine spaces and scenarios was such that they were invisible to the rest of society. Gaydar was engaged 24/7 and cruising was nonstop. Sex was everywhere, but it was still outlawed and still undercover. In a weird way, it felt free. Nowadays young up-and-comers romanticize it (if they consider it at all), but things could get dangerous and sometimes did. During those heady days fifty years ago, hook-ups and unhooking were rife. And, New York being the pressure cooker it has always been, hard work and survival were paramount. Finding a sidekick (a lover if possible) to share the workload, split the rent with, and maybe settle down with was a hopeful goal. Finding time to make art after taking care of survival details was vital in order to keep focused.

§

After a laundry list of generic roommates, Jimmy met Ken and things clicked. So Jimmy and Ken decided that they ought to find a more amenable place to live, one with studio space, optimally with mortgage potential instead of endless rent payments and looming threats of eviction. They went looking in the Lower East Side in the mostly abandoned and burned-out blocks where the down-and-outs were sleeping in doorways. Next to a homeless shelter on the outskirts of the Bowery, they found a century-old three-story brick building on an alley. It had once been a marble tile installation workshop, and before that a stable to house work horses and store wagons. Bringing the place up to code and making it livable took a while, but Jimmy’s skill set was more than equal to the task, and the couple were soon occupants and owners with a mortgage.

Jimmy and Ken worked various jobs and paid down the mortgage. Jimmy found time to paint. His work of the early to mid-1980s revisited his West Kentucky roots and started to grab the attention of gallery owners. He produced series of oil paintings that both extended his color palate and brought back some of the cultural iconography that his first drawings and paintings had celebrated.

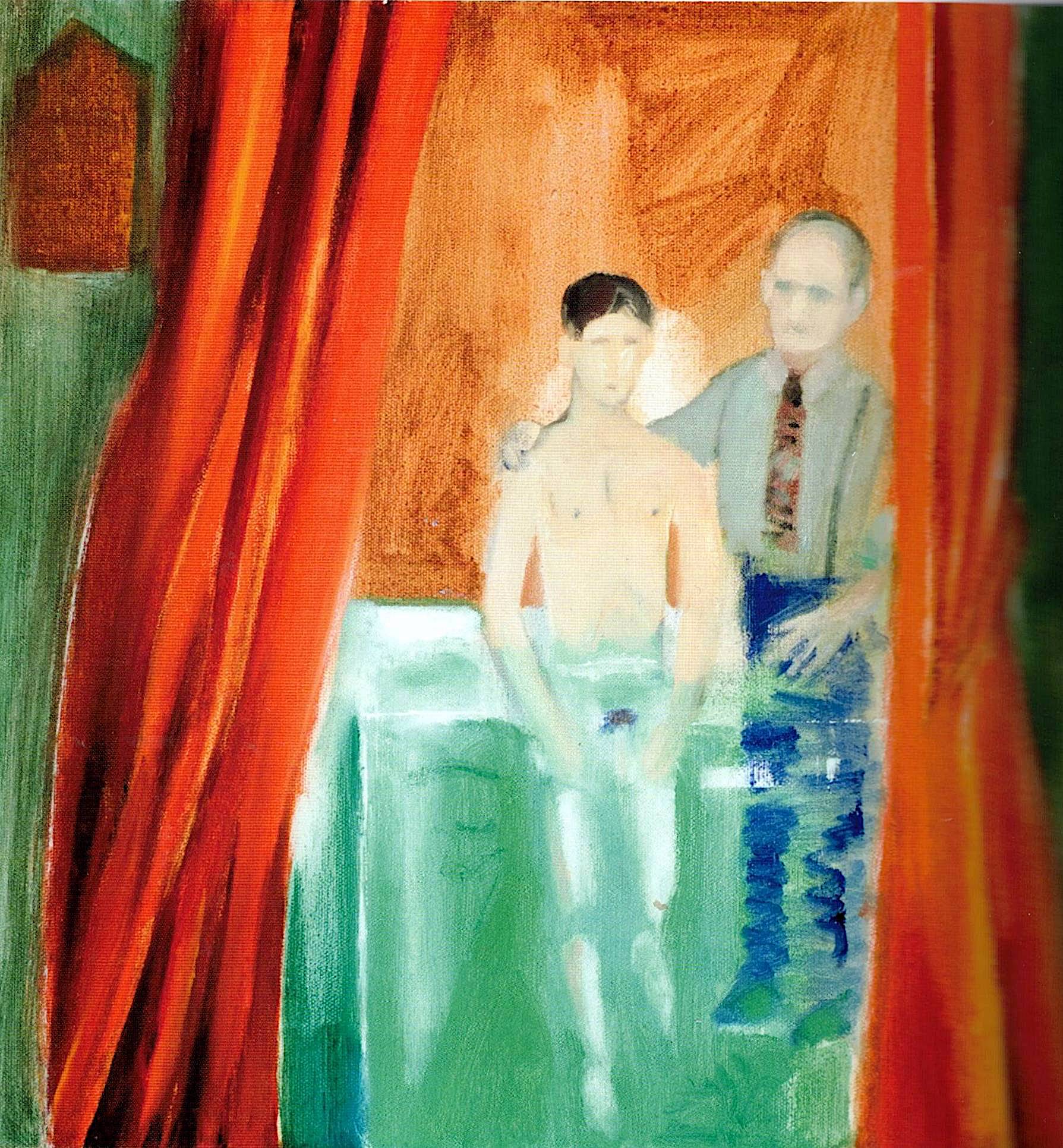

The most notable and dramatic (and achingly homoerotic) of these series was the “Baptism Set.” Each work featured a nude teenage boy standing full-frontal in the dipping tank alongside a shirt-and-necktie clad preacher who has him “in hand,” preparing to dunk him for Jesus. In Baptism at the Obine River, Baptism at Rives, and Baptism at Pilot Oaks, Jimmy had refreshed and reinterpreted medieval and Renaissance iconography of “religious” male nudity as often depicted in “John the Baptist dipping Jesus” paintings. In each of Jimmy’s updated versions, the religious essentials had been artfully queered.

Not long after these successes, in 1988, everything suddenly changed for the worse. Ken was diagnosed as HIV-positive, and overnight Jimmy became a caregiver. I won’t recite the horrors of the 1980s for gay men in general as their numbers were being decimated and they became a pariah class in the U.S. Jimmy Wright was holding down a job and taking care of Ken and trying hard not to despair.

One day when he was out looking for cut flowers, he bought a golden sunflower that had caught his eye. He brought it home hoping that its sunny face would brighten the mood. Soon, when it was no longer at the center of attention and had been relegated to a shelf, it had slipped his mind. It had wilted and dried and its petals had become shriveled and twisted. It was then that Jimmy noticed something and was inspired to paint a monumental portrait of the ravaged sunflower in oils, six feet square, the first of many such portraits to come. Sunflower portraits in soft pastels soon followed, talismans of remembrance, emotional emblems of affection, exultant lamentations. In the many metaphoric interpretations of sunflowers since that initial one, each was approached as though it was the first, and the complexities of each figuration, grounded on observation, was to be one of an ongoing series of innovative reinvention.

Exhibitions of his work began to be mounted by important galleries in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Success followed success, and the critics and art collectors began to pay attention. Jimmy’s work in pastels led to his joining the foremost organization dedicated to that medium in the country, the Pastel Society of America, where he is the current president. During a New York exhibition of pastel self-portraits, one of them, Self-Portrait with Green Hand, was singled out for special praise. Art magazine doyens rightfully compared it to famous pastels by Redon, Cassatt, and Degas. (This work is now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

An exhibition scheduled for March 2023 at Corbett vs. Dempsey Gallery in Chicago will feature etchings produced in the mid-1960s. Work by Jimmy Wright can be found on-line at jimmywrightartist.com as well as in the permanent collections of the Met, the Whitney, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the several galleries that represent his work in various American cities. Best of all, after a hiatus of two years due to the Covid pandemic, Jimmy is back at his easel.