FRANK KAMENY’S death last fall has pushed me to think about historical reputation. How do we evaluate the lives of those in the broad GLBT community who have assumed public roles, particularly in the world of political activism? Who gets memorialized? Who gets remembered as a hero? What achievements bring recognition on the historical record card?

Mainstream history books offer little guidance, as they still largely ignore queer topics. While our movement certainly exists in popular consciousness, it seems leaderless and in that sense different from other movements for social justice. For instance, in the long history of the black freedom struggle, at least a few individuals have won a secure place in the historical ledger as larger-than-life figures. Names like Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, W.E.B. Du Bois, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X have wide recognition. Mention “suffrage” and “feminism” and, at the very least, women such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Betty Friedan leap to mind.

But turn to our movement for sexual and gender justice, and the cupboard seems bare. I’ve heard claims made for Harvey Milk as the most important person in our movement’s history. But, I think, really? He was a local elected official for eleven months before being assassinated. Then there was Harry Hay, the founder of the Mattachine Society. Sure, he got something started, but he quit after two years when the going got tough, and then occasionally showed up later at Radical Faerie gatherings. Or Christine Jorgensen, who had very high visibility in the popular culture of her time, to be sure; but the coverage of her almost always took on the tone of freak-show reportage.

In the days after Frank Kameny’s death, there was lots of discussion on the web and on various email lists about his place in history.

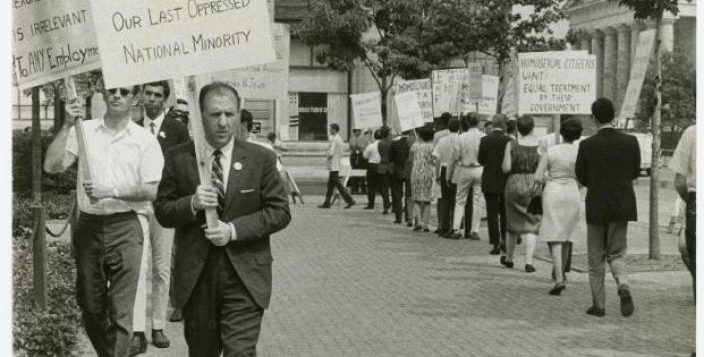

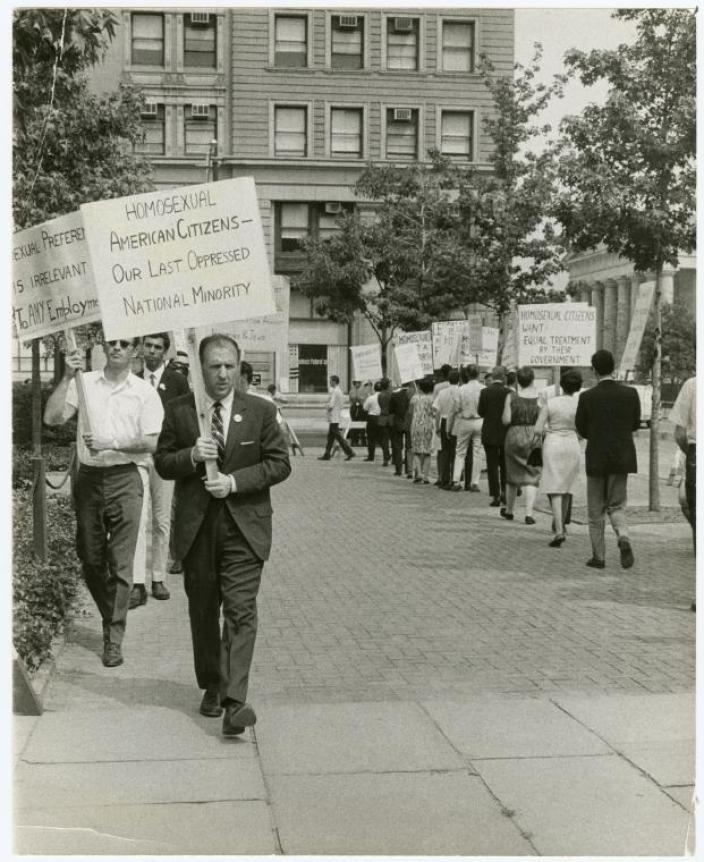

Kay Tobin photo; courtesy NY Public Library.

In an effort to think through the question of reputation, and of Kameny’s in particular, I went back to the research I did in the 1970s, a time so close to the events most associated with his public career that it could barely be considered history. I pulled out the text of speeches he gave and letters he wrote, documents that in the 1970s were still housed in his and other activists’ filing cabinets. I also found the notes I took of an interview with him that I did in 1978.

Born in 1925 in New York City, Franklin Kameny was a Harvard-educated astronomer working for the federal government in 1957. He had every reason to believe that, at the dawn of the space age, not even the sky was a limit to his career possibilities. But the feds found evidence of his homosexuality and, at a time when “sex perversion” made someone unemployable by both the government and any of its contractors, Kameny was fired and had no prospects of ever finding work in his field again. He appealed the decision, all the way to the Supreme Court, losing at every stage.

When these avenues of redress failed, he decided to fight in a different way. With some friends he founded the Mattachine Society of Washington (MSW). Over the next fifteen years, he fought tirelessly to change federal policy. He organized the first homosexual rights demonstrations in Washington. He got the American Civil Liberties Union to take on gay rights issues. He challenged the ban on federal employment in every way feasible. He took on the medical establishment’s claim that homosexuality was an illness, and coined the slogan “Gay is good.” In 1971, he ran as an openly gay candidate to be the District of Columbia’s non-voting representative in Congress. He helped found and served on the board of the National Gay Task Force, an early successful effort to create a national activist organization. By the mid-1970s, Kameny had the satisfaction of seeing two of his core goals achieved when the American Psychiatric Association voted to declassify homosexuality as a disease and the Civil Service Commission dropped its blanket ban on the employment of gays, lesbians, and bisexuals.

It would be hard to claim that Kameny continued to be a key mover and shaker after the mid-70s. However, he never ceased being an activist, and he always did much behind the scenes that was unheralded. He freely made himself available to individuals who experienced police harassment, lost their jobs, or faced blackmail because of their homosexuality. Later in life, other activists used Kameny’s career, with his permission, as a way of winning additional recognition from the federal government. His house is a D.C. historic landmark. The Library of Congress has acquired his papers. The Smithsonian Museum has displayed some of his activist memorabilia. The federal government has formally issued an apology for firing him.

WHAT WARRANTS assessing Kameny’s activism as significant in singular ways? For starters, through MSW he charted a whole new direction for homophile organizations. Evaluating where this small movement was in the early 1960s, he astutely characterized its work as either “social service” or “information and education.” In his view, neither promised much in the way of permanent change. Instead, drawing explicitly on the civil rights movement and the huge changes its public activism was achieving, he proposed an emphasis on what he called “civil liberties and social action.” Forget helping those individuals in need. Forget soothing efforts at educating and persuading the oppressor. Having tried unsuccessfully to win back his job with reasoned argument, Kameny now saw the opposition as “a ruthless, unscrupulous foe” with a “prejudiced mind … not penetrated by information.” To an audience of Mattachine members and sympathizers in New York, he urged “bold, strong, uncompromising initiative.”

In practice, this translated into a series of actions that moved beyond what homophile organizations customarily did. He pushed back against a right-wing member of Congress who targeted MSW. He sent a steady stream of letters to government officials demanding meetings. Most of all, he and those who shared this more assertive outlook took to the sidewalks of the nation’s capital. With large picket signs that boldly identified their issue as equal rights for homosexuals, they marched in front of the White House and other government buildings. Kameny eagerly talked to the journalists who flocked to the startling scene of homosexuals unapologetically proclaiming their cause.

Besides the federal government, Kameny aggressively took on the psychiatrists and their disease classification of homosexuality. In the past, Mattachine and the Daughters of Bilitis had reached out to medical and mental health professionals, but the approach was to win them over as allies and then support their efforts at new scientific research to challenge the sickness model. At its best, this approach led to the kind of work that Dr. Evelyn Hooker, a social psychologist, began producing in the late 1950s. Kameny was having none of this. He was not relying on experts. “I take the position unequivocally,” he declared, that homosexuality “is neither a sickness, a defect, a disturbance, a neurosis, a psychosis, nor a malfunction of any sort.” He went further. Taking on religion as well as science and law, he staked out this ground: “We cannot ask for our rights from a position of inferiority, or from a position, shall I say, as less than whole human beings.” To Kameny this meant that homosexual acts between consenting adults had to be defended as “moral, in a positive and real sense” and as “right, good and desirable, both for the individual participants and for the society in which they live.”

Militancy and pride—stances that seem so familiar to us today. They are the foundation upon which the gains of the post-Stonewall decades stand. But when Kameny first articulated these principles, they represented the frontiers of GLBT political thought. What allowed him to stake out that ground so fearlessly? Was it an intellectual confidence gained from having a doctorate from Harvard? Was it the happenstance of personality? Kameny was notoriously brash, sharp-edged, prickly. He didn’t care if his words offended someone. He could come across tough as nails, unsparing in his assessment of others, and unburdened by self-doubt. He seems to have escaped the internalized sense of inferiority that oppression often breeds.

One of my favorite statements of Kameny comes from a letter he wrote to a New York activist in 1965, the year in which he launched the Washington demonstrations: “I have always said that the world will take me on MY own terms, or it won’t get me, and the world’s loss will be greater than will mine; that when the world and I differ, I am right and the world is wrong and that if one of us or the other MUST change, it will be the world, because I won’t.” Can one imagine a stance better suited to a society in which all things queer were reviled, marginalized, or punished?

Kameny was not, of course, alone in his work. The positions that he espoused were enthusiastically embraced by a core of other activists, and the actions that he proposed came to fruition because others took them up, side by side with him. People like Jack Nichols, Barbara Gittings, Craig Rodwell, Randy Wicker, and Lilli Vincenz were among his partners in crime in the 1960s. But there’s no doubt that Kameny was staking out the ground and that he had the will—the bull-headedness, perhaps—to keep pressing forward and to succeed in bringing others along. The launching of campaigns against the federal government and the psychiatric establishment brought the movement’s biggest victories in the mid-1970s.

So, maybe he is the greatest gay hero, deserving a position at the front of the pantheon. But listen to what Kameny himself had to say in an interview in 1978. Stonewall, he asserted, was “a turning point,” accomplishing “what we had been trying to do for years and years and years and had never been able to do, and what we had anguished over endlessly: that the gay movement had never been a grassroots movement; it had never fired up the general gay community. Stonewall made the movement a grassroots movement.”

And Stonewall itself, he believed, came not from homophile activism but from a larger impulse sweeping the country. “What happened at Stonewall was very much in keeping with the spirit of the times,” he told me. “It was an era of tremendous ferment, of activism and militancy that hadn’t occurred in recent historical memory. … Riots were becoming commonplace in every part of the country. … And then you had the whole, very active and pervasive radical community and radical philosophy, which was setting a tone for everything that went on. Stonewall happened at the right moment, and it happened because it was the right moment.”

Kameny, never known for his self-effacing modesty, is telling us something important about movements, social change, and individuals. Can one imagine the doctors disavowing generations of theorizing about homosexuality without the militant disruptions of their staid conferences undertaken by this radical grassroots movement? Can one imagine the federal government retreating from their employment ban without all those disturbances of business-as-usual that the mass movements of the ’60s and ’70s regularly brought to Washington?

Kameny could see that the changes he espoused and the goals that he pursued were not about to be achieved until something else of consequence was added to the stew of social change: the energy and strength of mobilized communities, of populations in open revolt. A leader without many followers is not the recipe for permanent change. Kameny never could figure out how to create those armies of lovers clamoring for justice.

Kameny deserves a place in the historical record. He did make a difference in important ways. He is neither just one among the many, nor is he the one without whom the changes that we take for granted today would not have occurred. Kameny himself, I suspect, would be quite happy with such a spare and respectful assessment of his contribution. As he told Eric Marcus just over twenty years ago: “my life has been more exciting and stimulating and interesting and satisfying and rewarding and fulfilling than I ever could possibly have dreamed it would be.” He knew he had done right by himself and the world.

John D’Emilio is an emeritus professor of history and lgbtq studies at the Univ. of Illinois at Chicago. His most recent book is Memories of a Gay Catholic Boyhood: Coming of Age in the Sixties.