The Songs We Know Best: John Ashbery’s Early Life

The Songs We Know Best: John Ashbery’s Early Life

by Karin Roffman

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

336 pages, $30.

WHEN JOHN ASHBERY died at ninety in September, some lamented the passing of America’s greatest living poet. No one agrees on what is meant by “great,” but I was in a restaurant reminding myself of Ashbery’s early work when my server stopped at the table and said “Oh! I love Ashbery. Especially Some Trees.” That she, a random twenty-something, knew and liked Ashbery’s work from sixty years ago seems to add at least one fresh brick to the pedestal that has continued to lift him above the swarm of poets vying for lasting renown.

There is broad agreement that Ashbery was our most influential living poet. His style was so distinctive that, as Alfred Corn noted in these pages (Nov.-Dec. 2017), “we’d never heard anything like it.” We still haven’t. Whether that is good or bad is for poetry readers to say. I find some of his poetry immensely moving and some that does not convey meaning to me at all. Yet if Ashbery’s writing did not exactly lead to a school, it certainly generated an argumentative classroom of poetry. His way of writing was a breath of energy to many poets of the last half of the 20th century. Having felt his infused word-spray puffing into their ears, some ran to their desks, pen in hand, while others fled gibbering into the shrubbery. They still do, which speaks to the extent of his influence.

The book under review is about Ashbery’s early life, and the author, Karin Roffman—whose knowledge of poetry is impressive—devotes many pages to the poet’s childhood and its influences. Nor is this emphasis misplaced: Ashbery’s childhood experiences and memories remained a recurring theme of his work for his entire life. Looking back to some of the juvenilia included in this book, I notice two things. First, the work of teenage Ashbery, hiding his sexuality in diaries and coded Latin phrases, is remarkably similar in style to what the mature writer gave us. The Ashbery “sound” was simply enriched over time. Second, his juvenilia were shockingly advanced not only in how he used words, but in what words he used. Here was a teenager who was reading Hazlitt under the bedsheets. His photographic memory apparently allowed him to retain every word he saw, and he deployed this collection of terms at seventeen with a clarity that must have been blinding to his contemporaries (and his teachers).

We are then treated to his early years in college, where he heard himself called “gay” for the first time while cruising the bars. During this period, he was still sending smokescreen letters to some friends, pretending to be interested in women, and trying to seem straight at Harvard, which at this time (the late 1940s) expelled known homosexuals. He managed to remain in college while ramping up his sexual explorations, returning to his family farm and its hated apple-packing chores as needed.

Although Ashbery is best known as a poet, he also wrote plays and fiction. One of the hilarious moments in his college career was the “premiere” of the parody Return of the Screw, which involved “a Harvard student’s nearly erotic encounter with a Dean Flotcher.” Later, more serious plays included Everyman and The Heroes. The latter was produced to good reviews. He could also be appallingly direct with friends and colleagues. Imagine saying to the young Samuel Barber: “… but I don’t think you should write another major work.”

Ashbery sometimes baked word-cakes with unusual ingredients, giving the reader no real idea why crêpes made with pineapple and opium found a place next to formaldehyde, tulips, farts, and swans. (Here’s a challenge: can you spot which objects are from a single Ashbery poem and which I invented?) That he was once inspired to write a poem simply to have fun listing the contents of thesaurus entries is therefore not a surprise. One of his own high school couplets carried a foreshadowing of many works to come: “So, musing, she fell asleep, still sorry about the bed/ Glad of the flickering stars, now green, now red.// Whoever criticizes this poem adversely must admit that it is at least bizarre.”

Yet there is a lyrical, boy-in-love Ashbery who is sometimes missed by those who lose their way in the word-storm. The poet once asked simply: “Is there something intrinsically satisfying about not having the object of one’s wishes, about having miscalculated?” Roffman notes that he recognized in his childhood what he rediscovered at Harvard: “unrequited love was good for his writing.” His memory for words extended in the emotional arena to long-term recollections of specific experiences, such as ill treatment at Deerfield, happenings in his family, and boys he had wanted, the latter a growing and rapidly-changing list.

Ashbery was to a certain extent a reactive poet. Throughout these early years we see how his dry periods, some of them lasting many months, were often followed by significant flurries of poetic creation apparently originating from an incident, a work of art, a person met, or another writer’s work. One of the great strengths of this book is that the author understands the nature of the creative process and offers clear descriptions of how some of the inspirational sequences happened. Yes, she is using some of Ashbery’s own diaries, which helps, but a biographer still needs a sense of judgment to sort out what’s worth mentioning and what’s not.

Roffman gets a little breathless when she plunges into Ashbery’s slut period in his late twenties, shortly before he left for France. She makes a valiant effort to accurately track and describe in short sentences who was sleeping with whom, who was angry with whom, and so on, but also who was collaborating with whom among his many friends and artistic colleagues. While entertaining, I’m not convinced it was worth the effort to include all this in the poet’s biography. In general, the last section of the book feels the weakest, perhaps because it is so clearly a transition to a significant change in his life. The young people are starting to scatter into life’s diverging channels; Ashbery is becoming a “known” poet when Some Trees wins the Yale Younger Poets prize; and soon he’s off to Europe.

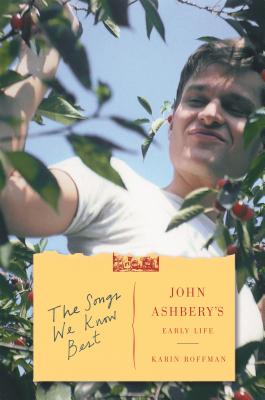

I have never mentioned a book’s cover in a review, but this time I must. The leafy photo of a tender, teenage Ashbery picking cherries in the family orchards was taken by his father Chet, an accomplished photographer as well as a farmer. Its use as the entire cover, with a superimposed “postcard home” bearing the title, is a choice of genius, presumably by jacket designer Sarahmay Wilkinson. The photo has meaningful links to every chapter of the book and is a poignant, perfect image of the pleasure and pain of formative youth. The publisher took a design risk with this unusual cover and it worked. Roffman’s subtitle suggests that she may already be working on Ashbery’s subsequent years. It is a life story well worth telling, and Roffman has proved equal to the task.

Alan Contreras is a writer and higher education consultant who lives in Eugene, Oregon.