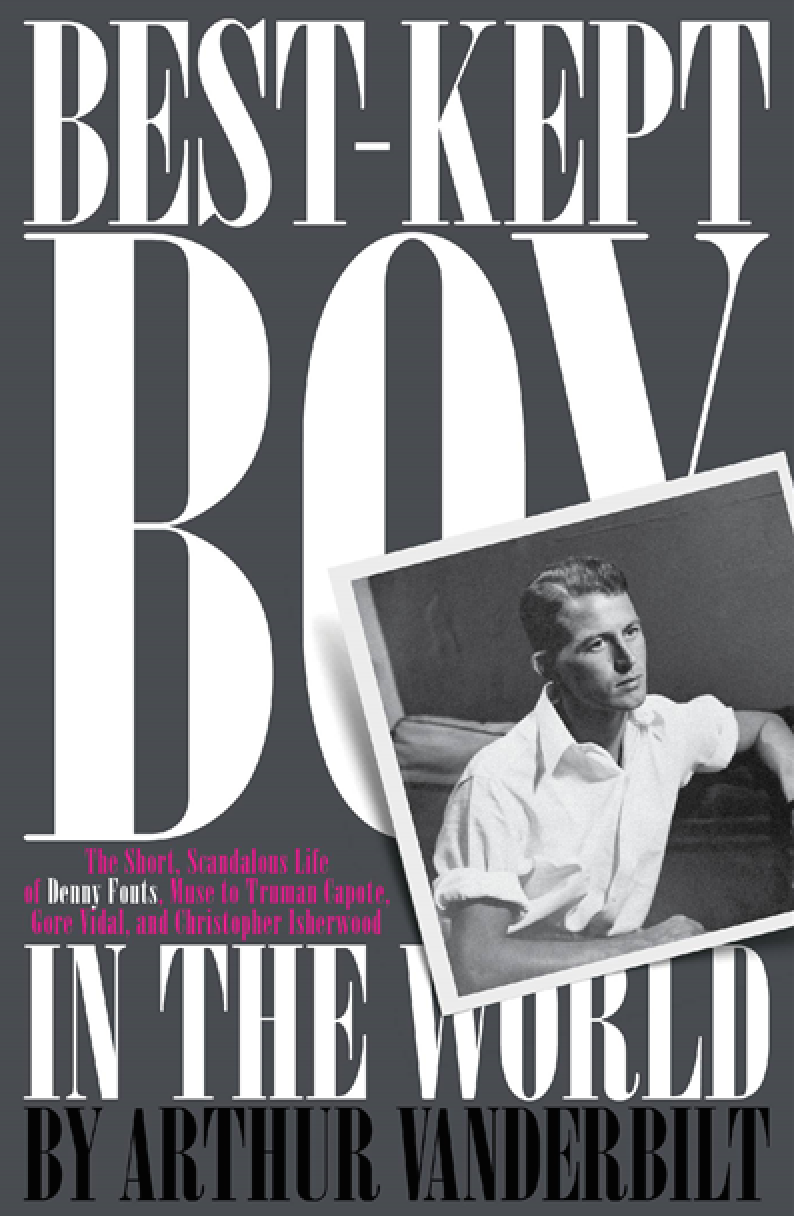

The Best-Kept Boy in the World: The Short, Scandalous Life of Denny Fouts, Muse to Truman Capote, Gore Vidal, and Christopher Isherwood

The Best-Kept Boy in the World: The Short, Scandalous Life of Denny Fouts, Muse to Truman Capote, Gore Vidal, and Christopher Isherwood

by Arthur Vanderbilt

Magnus Books. 190 pages, $19.99

THERE’S an oft-repeated quotation by Truman Capote, who learned of Denham Fouts’ 1933 meeting with Adolph Hitler through his affiliation with the brother of World War I flying ace Manfred “the Red Baron” von Richtofen. Capote quipped that “had Denham Fouts yielded to Hitler’s advances there would have been no World War Two.”

“Denny Fouts” is a name that circulates in the margins of gay history.

The rationale for a biography of Fouts is contained in the book’s subtitle, which serves as a defense and a caveat, alerting us that Fouts may be less interesting than the people around him. We might even be forgiven for concluding from this biography, to paraphrase Gertrude Stein, that there isn’t much there there. It’s not that there isn’t sufficient drama or adventure in the life of this boy from Jacksonville, Florida, born in 1914, but that evidence from Denny’s own hand—letters, diaries, journals, etc.—is relatively thin. Author Arthur Vanderbilt presents his subject not as someone who speaks for himself but as an appendage to others, usually men of wealth and position and/or noteworthy talent. Vanderbilt spends page after page laying out their background stories so that we understand why each one fell for this Southern belle who was by most accounts witty and charming but also deeply insecure. This is Vanderbilt’s own reading of Fouts, who could never understand why he was so attractive to so many, but who used his looks to secure the life of the “best-kept boy” around.

A friend who worked in a bookstore introduced young Fouts to novelist Glenway Wescott, a Midwesterner whose own European expatriation in the 1920s gave him the experience and outward veneer of an homme du monde. Fouts, realizing he didn’t want to be a street whore, yet sensing he had something of value to put on the market, asked Wescott’s advice about how to become a “kept” boy. “To begin with,” Wescott intoned, “you must never use that word—‘kept.’ Think of something you want to do that takes money to learn. Then ask someone for help and guidance. You’ll get much more money that way than by coming at it straight on.”

So began Fouts’ worldwide peregrinations in the company of the well-heeled or the simply raffish: a German baron swooned over him from New York to Berlin; a Greek shipping tycoon snagged him while hitchhiking to Venice and took him on his yacht, from which Fouts, taking up with a sailor onboard, jumped ship with stolen money so the two could whoop it up on Capri. Then there was Evan Morgan, the last Lord Tredegar, walking through a hotel lobby with his wife, trailed by a “retinue of retainers,” who spotted Denny just as he was about to be arrested for skipping out on his bill. Announced Lord Tredegar to the guardians of the law: “Unhand that handsome youth, he is mine.” He began his ascent in New York City in the early 1930s, where he turned heads every time he entered Jimmie Daniels’ Harlem nightclub, his favored hangout—perhaps because, as a Southerner, he was breaking the color line and defying family traditions. It soon became apparent to Denny that “wherever he went … he commanded every room he entered.”

Lord and Lady Tredegar traveled the world with Fouts in tow; in China, Denny, visiting the local opium dens, picked up the habit that would dog him the rest of his life. Back in Tredegar Park—think Downton Abbey for madcap bohemians—Denny joined in manifold festivities among a cast of pampered eccentrics and artist celebrities, including H. G. Wells, Lord Alfred Douglas, George Bernard Shaw, and Lady Nancy Cunard. Here, according to Vanderbilt, drink and drugs fueled a continuing roundelay of circus-like weekend gatherings. At one, Prince Paul of Greece, exiled in London since the abolition of the Greek monarchy in 1924, took a shine to Fouts and swept him up for a long Mediterranean cruise—perhaps Denny’s greatest catch and one of which he would boast for years to come.

His relatively fleeting alliance to the Prince may have proved Denny a courtesan worthy of the highest echelons of European royalty, but it was his long relationship with Peter Watson, son of Sir George Watson, the man who made his fortune with the invention of margarine, that finally established Denny’s reputation, for better or worse. When Sir George died, his son Peter, Eton and Oxford educated, with a passion for modern art, was able to live off his inheritance like an English gentleman and pursue the latest in School of Paris paintings.

Peter Watson was well connected to the worlds of art and literature. Society photographer Cecil Beaton, although himself madly in love with Watson (who never reciprocated, though he gave friendship), said that Watson was “an independent, courageous person.” On Watson’s first meeting with Denny at a nightclub, Watson followed the young beauty back to his hotel, where Denny “gave himself cocaine injections.” Of this fateful meeting, Vanderbilt writes: “And there, in Denny’s hotel room, Peter stayed. … [He] had to possess this god-like creature … as he had to possess the museum quality paintings of de Chirico, Gris, Klee, Miro, and Picasso he had been collecting. Denny … sensed he had found himself someone who might be a worthy acolyte. … Peter was hooked.” Thus began a peripatetic episode of l’amour fou in London and Paris, a relationship we might today call one of co-dependency, complete with arguments, break-ups, and drug rehabs. A friend characterized Denny as “the great, destructive love” of Peter’s life. Despite himself, Peter recognized that he and Denny were from different worlds: “We never shared any intellectual interests whatsoever and he always resented that side of me.”

As war approached, Peter sent Denny to America, where he eventually landed in California and was taken in by British expatriate Christopher Isherwood, then writing for the Hollywood film industry. Denny proceeded to join Isherwood in his study of Vedanta, a religion related to Hinduism. The two supported each other through a period of stable daily habits and celibacy, which was natural to neither. Like Isherwood, Denny was a conscientious objector during the war, which led to his working at a logging camp, where he entertained the workmen with tales of his European adventures. Denny also began taking correspondence courses to get his high school diploma in preparation for a “program of higher education to become a psychiatrist.” Vanderbilt never inquires into the reasonableness of such a course of action. In any case, Denny’s own studies didn’t stick, but Isherwood would turn him into a character in his novel Down There on a Visit. Vanderbilt produces Isherwood’s original diary entries about Denny followed by the corresponding fictional passages, which often follow almost word-for-word.

When Denny returned to Paris after the War, Peter Watson’s elegant apartment on the rue du Bac was a shambles. But Denny soon took up his old habits, which now included heroin and teenage boys. (Denny once boasted of having fucked his pretty younger brother when both were adolescents.) Peter fled for New York, leaving Denny in the apartment with his latest mignon. In this immediate postwar period, Denny became a vampiric figure holed up in his bedroom, strung out on drugs but able to receive guests, eventually making it out into the waning Paris sunshine. Gore Vidal, a freshly minted novelist, introduced himself to Christopher Isherwood at Paris’s famed café Les Deux Magots and got himself invited to meet Fouts the next evening. Vidal would later claim that Denny’s “legendary beauty was not visible to me.” This didn’t stop him from also morphing Denny into a fictional character in his novel The Judgment of Paris? (1952) as well as in a short story titled “Pages from an Abandoned Journal.”

Glimpsing the photo of the young Truman Capote that graced Other Voices, Other Rooms, Fouts is reported to have sent Capote a blank check with the simple message: “Come.” When they finally met, the two Southerners “hit it off instantly.” Capote thought Denny “the single most charming-looking person I’ve ever met.” Soon enough, Capote persuaded Denny to go to a Swiss drug rehabilitation clinic on the promise that they would both meet up in Italy afterward, a promise that Truman had “no intention” of fulfilling, afraid as he was of Denny’s “derelict life” and, as Vanderbilt supposes, “what his own future might hold—Denny as the ghost of Christmas Future.” All the same, Denny made it into Capote’s unfinished last book Answered Prayers, this time under his own name, as Truman recounted and perhaps embellished the cautionary tale.

The main body of this biography is too often the peripheral stories that the author feels compelled to share: Isherwood’s search for spiritual balance after his exile from England; Vidal’s loss of his mythic youthful love, Jimmie Trimble, whose own story bled into Denny’s when Vidal wrote fiction; and Capote’s early innocence eroded by contact with the drug-addled Fouts. As it happens, Capote missed the moral of Denny’s story, drifting into his own addictions. Best-Kept Boy in the World brought out the scold in me; for all the many interventions, Fouts never received the tough love that he needed to get well. Instead, everyone—Peter Watson excepted, for he ultimately abandoned Denny to his own devices—played adoring witness to his self-destruction. If nothing else, he had a talent to amuse.

Allen Ellenzweig is the author of The Homoerotic Photograph and a frequent contributor to this magazine.