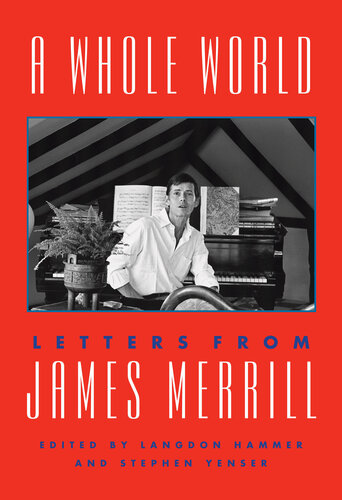

A WHOLE WORLD

A WHOLE WORLD

Letters from James Merrill

Edited by Langdon Hammer and Stephen Yenser

Alfred A. Knopf. 700 pages, $40.

JAMES MERRILL (1926–1995) was one of the most honored and admired American poets of the second half of the 20th century. As Stephen Yenser puts it in the introduction to A Whole World: Letters from James Merrill, Merrill was “different from both his debonair contemporaries in the New York School and the more theatrical and publicized ‘confessional’ poets.” In other words, Merrill was neither a Frank O’Hara nor an Allen Ginsberg, two other important gay poets of his generation. His poetry, with its fluent balance of refinement and casualness—full of “taut alertness,” as literary critic David Kalstone once observed—can at first seem to be little more than highly refined surface effects. In fact, while Merrill was “shy of ideas in poetry,” as his poet friend J. D. McClatchy once noted, “the urgency of the heart’s desires [was]his constant subject.” He is without doubt one of the great poets of the homosexual experience, one who struck an impeccable, polished balance between the colloquial and the refined.

Born into a family in which he “never had to fret about money”—his father cofounded the investment firm Merrill Lynch—James Merrill received a first-rate education. His character and sensibilities—genial, urbane, courteous and courtly—took root early. By the time he was twelve, he could report to his father that he was about to attend his eighteenth opera. During his college years, he began to fashion himself into “a superb dilettante.”

At Amherst, where he majored in English, Merrill met his first lover, Kimon Friar. When his mother got wind of the relationship, she insisted that he see a psychiatrist. “What is the point of going to a doctor if your mind is made up?” he wrote Friar in 1946. “I cannot discover myself until I have a chance to be myself, and that chance is what you have given me.” In addition to being Merrill’s boyfriend, Friar, who was fifteen years older than Merrill, also briefly served as the would-be writer’s literary mentor.

In several of the letters written in his early twenties, we see Merrill finding his way as a writer. His first book of poems, published in 1951, received a “horrible review” in The New Yorker. “I don’t mind as much for myself,” he wrote his mother, “as I do for, say, Daddy who could so easily feel it’s all a waste of time, what I’m doing.” But he pressed on, writing a play and a novel, both of which received mixed reviews, and another book of poems.

He pressed on in love as well, taking up with many other lovers after Kimon Friar. His early love letters—indeed, all of his love letters—are full of youthful effusiveness. “I cannot contain my feelings. I tremble,” he wrote to another short-lived boyfriend. “What more can I say to you today? darling, darling,—without you, none of this.” Each affair, Merrill said, was “trying to recapture the infinite sensuous receptivity of the little child.”

In 1953, Merrill met David Jackson, who was to become his lifelong companion. Their friend, the writer Alison Lurie, thought it “the happiest marriage I knew,” more affectionate and considerate than most heterosexual marriages. But even in his first letters to Jackson, Merrill acknowledged that they could not be everything to each other. By the mid-1960s, they were each taking on other boyfriends and tricks—“delicious Adventures,” Merrill called them. These extramarital affairs were, he said, “a phase eventually reached by many sensible couples—the homosexual ones at least.” In one long letter, he wrote: “If you doubt that one can love more than one person at a time, reread The Tale of Genji.” This life of “multiple affections” brought its share of “troubles [and]ambivalence,” but over time Merrill came to see it as also supplying “the stuff of my art.”

Throughout the ’60s, Merrill continued to bring out books of poems. Nights and Days (1966) won the National Book Award. By 1972, he had, according to the formidable critic Helen Vendler, come to that place in his career, “when readers actively wait for his books: to know that someone out there is writing down your century, your generation, your language, your life.”

Two years after Merrill met Jackson, they began amusing themselves with evenings in front of a Ouija board. What began as a pastime soon became a “marvelous nightly pudding” of messages from the spirit world. In a long letter to his mother, Merrill described having “talked” to the spirit of a first-century Jew named Ephraim. “If you think I am mad,” he told her, “do so. For myself, I believe it utterly.” Ephraim’s revelations not only provided Merrill with “thrills and chills” but also eased his anxiety about death and, even more importantly, provided inexhaustible material for poems. The evenings with the Ouija board were, he later said, a “kind of map of my imagination.”

By the mid-’70s, Merrill was hard at work on a long poem called “The Book of Ephraim,” based on his “compact with the Powers.” He realized this magnum opus “could be perfectly awful, or it could be the Divine Comedy.” Several of the letters give us an inside look at his thinking about this ongoing project. “If the result isn’t Goethe or Dante,” he wrote to his nephew, “tant pis.” The ninety-page poem was eventually published in Merrill’s seventh book of poetry, Divine Comedies, and went on to win the Pulitzer Prize in 1977. Many found “The Book of Ephraim” baffling, including the poet Donald Justice, who called it an “aberration.” Undaunted, Merrill and Jackson continued the ghostly communications, Jackson handling the tea cup that spelled out the messages from a host of spirits, including W. H. Auden and Maria Callas, and Merrill taking down the dictation. Two more long poems were the result, the first of which, “Mirabell,” won the National Book Award. The entire three-poem epic was collected under the title The Changing Light at Sandover, which ran almost 600 pages long.

Because he had trouble keeping a journal for more than a week, Merrill acknowledged that his letters have “got to bear all the burden.” They are by turns gossipy, philosophical, extravagant, humdrum—“gabby and dull,” as he himself noted. Many describe the goings-on in his quotidian life: throwing parties, meeting people, getting and giving advice about work in progress, cruising for sex, cooking (“I make miracles in the kitchen”), bridge games, various ailments and diseases, what he’s reading, and the guests that he and Jackson entertained at one of the three houses they maintained, in Stonington, Connecticut, Key West, and Athens. Social overextension became “the lifelong rack I’ve been stretched upon,” he told one correspondent.

The letters abound in the hilarious juxtapositions of a rich and diverse gay life. A paragraph that begins with a reference to Rilke ends with a request for an inhaler for poppers. Another letter brings up leather bars, pressed caviar, a Broadway musical, and a triptych by Hans Memling. What’s mostly missing from the letters are politics and current events. Merrill did not read newspapers and once wrote to J. D. McClatchy that he had never voted. “Nothing is more welcome than an incentive to ever harder work,” he wrote to another poet friend. “And while you can’t do much about Bosnia, you can improve this poem.”

What the letters do contain is a record of the vicissitudes of Merrill’s many love affairs. Both he and Jackson often fell for people “with the bad seed already sewn [sic] in them.” Indeed, Merrill’s “four most consuming lovers,” as he confessed to a former boyfriend, were addicts. Despite acrimonious breakups, by and large Merrill remained affectionate and loyal to his former inamorati. He would often write to one former lover about his newest flame. By his mid-forties he concluded that his “exhausting erotic race” had reached the finish line, yet he always managed to embrace the “innocent wonder” of falling in love again. “Isn’t life strange, the way one gets what one longs for again & again as soon as one no longer cares?”

With the emergence of HIV, Merrill began to acknowledge that his promiscuity—“my tried and true friend for long spells”—might have to be curbed. In 1985, his dear friend David Kalstone was hospitalized with AIDS and died soon after. “It’s so shattering,” Merrill wrote to another of his former lovers. “He’s the first person I know to be stricken.”

Merrill himself was diagnosed a year later. To his correspondents, he maintained a philosophical attitude, writing to one friend: “The Voltaire in me wants to say that whatever happens is for the best; it’s only in movies that lives are ‘wrecked.’” To another, he notes that now that he’s approaching seventy, regardless of any condition, he is “wanting things tidied up.”

The final letters, written in the last weeks of his life, are heartbreaking. He’s planning outings to the opera and pouring out a lifetime of wisdom about the craft of poetry to a young protégé, a high-school senior who was interested in literature. The final letter, to André Aciman, written five days before he died, is a model of courtesy, full of expressions of appreciation from one writer to another.

Back in 1970, Merrill wrote to the 37-year-old Kalstone, who was despairing of his own place in the world of letters: “Nothing helps except to do one’s work and to love as much as one can, wherever one can.” Merrill’s letters offer beautiful witness to this double life project.

Philip Gambone, a regular contributor to this magazine, recently published his fifth book, As Far As I Can Tell: Finding My Father in World War II (Rattling Good Yarns Press).