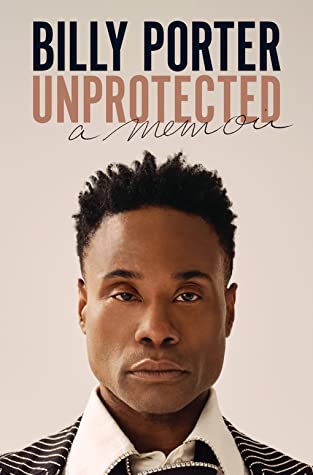

UNPROTECTED: A Memoir

UNPROTECTED: A Memoir

by Billy Porter

Harry N. Abrams. 288 pages, $28.

WHILE MANY will say that Billy Porter’s career is the stuff of legend, from his incredibly fabulous acting style to his almost godly singing voice—performing in Five Guys Named Moe, Smokey Joe’s Café, Grease, and later as the iconic Lola in the hit Broadway show Kinky Boots and as Pray Tell in the critically acclaimed TV series, Pose—one must remember that most legends are rooted in historical factuality. In his new memoir Unprotected, Porter reveals the truth, much of it painful to remember, about his formative years and early career in a book that’s a good story, a soulful ballad, and a scream for understanding, among other things.

From his beginnings in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, living as a child in a Pentecostal household, Porter recounts all the ways in which the world targeted him for being different, whether questioned for his lack of “masculinity” as a young queer kid or ridiculed for the way that he gravitated toward the arts. The latter were both a means of creative expression and an escape from the abuse inflicted by his stepfather and by the church. He finds that some of his experiences as a child have left a mark on his ability to connect with men romantically and emotionally as an adult.

Santiago Felipe/Getty Images.

In high school, he finds solidarity and artistic fulfillment in the theater. From The Wiz to Dreamgirls, Porter locates his musical inspirations, acknowledging the divas of the past that allowed this young artist to see himself reflected in Black artistry. While he’s considered a giant in the industry today, there’s no lack of humility as Porter profiles the “angels” who nurtured his voice and supported him financially, spiritually, and emotionally during his endeavors as a struggling artist, all the while inspiring him to pay it forward by becoming a mentor to new generations of artists.

The title of one story, “Unprotected,” can be taken in more than one sense of the word, as Porter recounts his years as a Black queer youth who tested HIV-positive at a time (2007) when the cocktails were available but people were still dying of AIDS. As the book moves between the past and present, the parallels between the AIDS plague and the Covid pandemic appear as nothing short of devastating. He bears witness to the inhumanity and indifference of those in power, the failure to learn from the past, and the cruelty of bigots and right-wing politicians past and present.

Still, there are glimpses of light in the darkness. Porter’s love for his art and his communities shines through on every page, furnishing him with the drive to continue working in fields that often prevented him from using his talents to their full extent. When his creative ambitions are stalled by the pandemic, he sees this as a good time to face his demons and to reckon with the trauma that he experienced in his earlier life; and he meets this challenge with honesty and care. While this reckoning is complicated and painful, it’s a journey that many readers may recognize and identify with.

Porter’s talent as an artist is what has given him the confidence to forge ahead despite the obstacles thrown up by those who have a problem with his unapologetic queer femme nature. In doing so, he has provided the world an icon for the new generation. Perhaps no sentence in Unprotected better sums up his message than this: “I discovered midway through the writing of this book that my story was not just about overcoming adversity—my life is a testimony to the power that art has to heal trauma.” It may not be a form of therapy that works for everyone, but reading this book can at least provide some helpful inspiration.

Michele Kirichanskaya, a freelance journalist from Brooklyn, creates content for The Mary Sue, GeeksOUT, and other platforms.