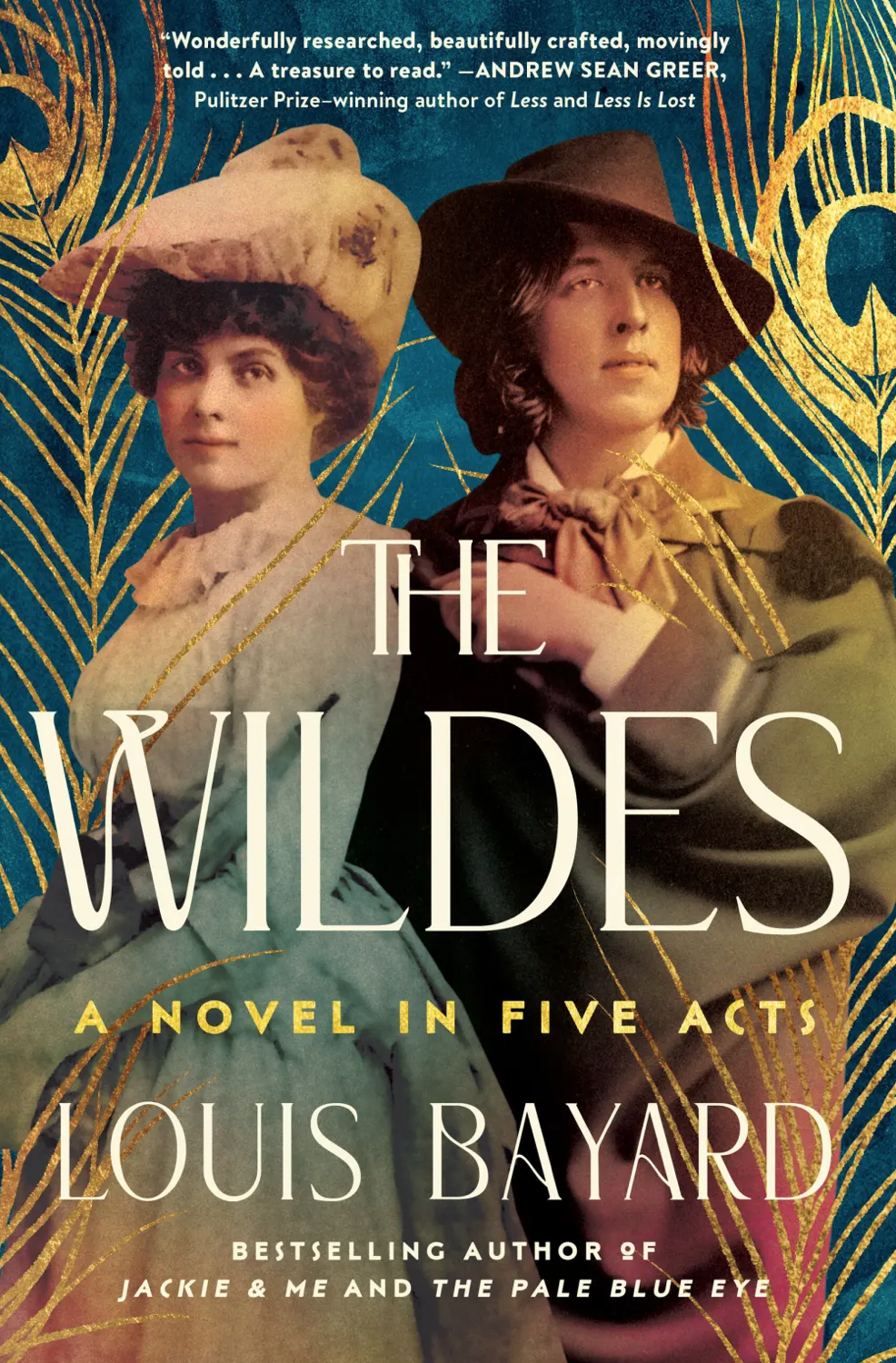

THE WILDES

THE WILDES

A Novel in Five Acts

by Louis Bayard

Algonquin Books. 304 pages, $29.

THE CHALLENGE of writing historical fiction—creating an interesting story with lifelike characters within the constraints of historical facticity—becomes even more difficult when the historical figures and events are widely known or readily googled for a quick refresher. The more famous the people and events depicted, the higher the expectation of accuracy, or at least verisimilitude, with respect to the characters’ actions, manners of speech and dress, modes of transportation and communication, and so on.

Louis Bayard has proven himself equal to this challenge in such novels as The Pale Blue Eye (a retired New York policeman’s investigation of a murder at West Point in the 1830s), Courting Mr. Lincoln (Mary Todd’s pursuit of Abe), and Jackie & Me (Ms. Bouvier before JFK). His latest novel, The Wildes: A Novel in Five Acts, focuses on Oscar Wilde’s long-suffering wife Constance and their two young boys, Cyril and Vyvyan, as they cope with Oscar’s philandering and the aftermath of his trials and exile.

The novel opens in 1892 at a country house in the Norfolk region that the Wildes have rented ostensibly so that Oscar can complete a play (probably A Woman of No Importance, first performed in 1893). Oscar works diligently on the play while his wife and his mother, the imperious Lady Wilde, enjoy the idyllic setting. But when Lord Alfred Douglas—“Bosie,” the son of the Marquess of Queensbury—arrives, tensions start to rise. Oscar explains to Constance and Lady Wilde that Bosie is there to work on his translation of Wilde’s Salome (published in 1893). But Constance senses that translating is the least of Bosie’s reasons for being there. Slipping into Oscar’s bedroom late one night and finding the bed empty, she sits and waits for her husband to return. In the sparkling yet cryptic dialogue that ensues, Constance makes it clear that she is aware that Oscar and Bosie are sneaking into the attic late at night for carnal enjoyment. “And you!” she rages. “And your tales of old whores and old syphilis, and we could no longer lie together and be husband and wife, but you … make someone else your wife, and your own son slumbering two stories below and me alongside and your mother two rooms over, and you dared!” The next morning, Constance, Cyril, and Lady Wilde depart for London, leaving Oscar and Bosie on their own.

The “entr’acte”—this is “a novel in five acts”—includes transcripts of Wilde’s two 1895 trials, the first as plaintiff against the Marquess of Queensberry for his slanderous accusation that Wilde was a “posing somdomite [sic],” the second as defendant in a criminal trial for “gross indecency.” It also includes a letter from Wilde to Lord Alfred from Reading Gaol, in which Wilde laments Bosie’s vanity and his profligacy with Wilde’s money: “I had no idea that the first would bring me to prison and the second to bankruptcy,” he writes.

The narrative picks up in “Act Two” in 1897, at a villa in Bogliasco, Italy, where Constance has exiled herself and her boys. She has fled England for its barbarous treatment of her husband and family, having dropped the name “Wilde” in favor of “Holland.” Constance has never discussed with the boys the reasons for Wilde’s imprisonment and the family’s exile, but Cyril learns the truth by reading some Irish newspapers. He is angered by the ignominious stain on the family name. In a letter to Vyvyan in 1914, he writes: “All these years my great incentive has been to wipe that stain away; to retrieve, if may be, by some action of mine, a name no longer honored in the land. … This has been my purpose for sixteen years. It is so still.”

To Cyril, retrieving that good name means that “I must be a man.” We find him next in the trenches in France in 1915, a sniper in the British Infantry in the mire of World War I. He endures shelling, horrid weather, and the incompetence of his fellow soldiers. When one is injured, Cyril tries to comfort him by telling him about “a very selfish giant,” the story his father had told him and Vyvyan when they were much younger. When the soldier dies, Cyril is called upon to inform the man’s family, deciding after some soul-searching to lie about how their cowardly son died.

Act Four, set in London in 1925, features a long dialogue between Vyvyan and Lord Alfred, who has tracked Vyvyan down and taken him to an underground bar that he later discovers is a gay bar. The dialogue provides insight into Lord Alfred’s self-aggrandizing take on the affair. He laments that “Wherever I go in this world … I shall forever be your father’s concubine.” He denies any complicity in the scandal, blaming it all on Wilde. This dialogue also might remind readers of Wilde’s essays The Decay of Lying or The Critic as Artist.

Act Five returns us to the Norfolk country house we entered in Act One. This chapter belongs to Constance. With a show of determination that surprises both Oscar and Bosie, she lays out her conditions to them regarding their future conduct. She proves to be every bit as eloquent in speech and as resolute in purpose as Oscar. Even readers who have studied Wilde, the trials, and the doomed love for Bosie may be surprised by Constance’s ultimatum to her husband and the young man who stole his heart.

Such an ultimatum may or may not be historically accurate; we will never know. But as an explanation of the affair and a preview of its aftermath, which did in fact involve an immediate rupture in their marriage and Constance’s departure, it can’t be too far off; sparks must have flown. In the end, what makes a historical novel believable is its ability to fill in the gaps, the private dramas, with stories that seem almost inevitable to account for what is known, and Bayard has proven himself to be a master at it.

Hank Trout, a frequent contributor to these pages, is the former editor of A&U: America’s AIDS Magazine.