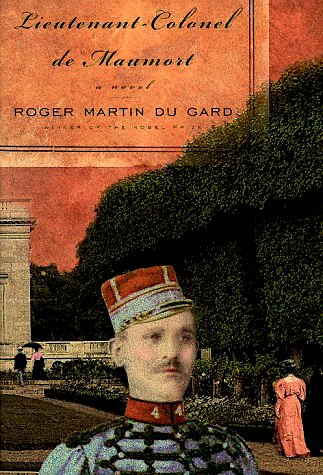

RECENTLY, while on vacation in Savannah and browsing in a wonderful little bookstore, I came across a thick volume by Roger Martin du Gard titled Lieutenant-Colonel de Maumort. I had never heard of either the book or the writer but later learned that du Gard won the Nobel Prize in 1937 and that this translation was published with great fanfare by Knopf in 1999. Intrigued, I purchased it, and then the surprises began.

Maumort is not so much a novel as a fictionalized memoir—at least in its present state. Du Gard changed his mind several times while writing it regarding how exactly to tell the story; more on that later. What surprised me the most was a) how little known it is today, and b) how incredibly frank and nonjudgmental it is on sexual matters in general and on homosexuality in particular. Indeed, du Gard, who was a close friend of André Gide (in fact, the work is dedicated to him), spends a lot of time contemplating why the Lieutenant-Colonel did not turn out to be homosexual, despite the fact that many of his early sexual forays—one could even argue, his most significant ones—were with men.

The recollections begin, conventionally enough, with the 77-year-old Maumort remembering how, at age ten, he saw a group of naked girls bathing in a pond. He experiences a feeling of “absurd guilt” as he suddenly grows conscious of the physical differences between himself and the girls. He also experiences strange pangs of shame as he ponders the existence of what his old servant Zelie, upon washing him, had once referred to as his “li’l gentleman.” The young Maumort becomes obsessed with the girls, but just as quickly this obsession is supplanted by the arrival of a cousin named Guy who comes to live with him and his family at their estate.

In Maumort’s words: “my first impulse towards Guy was not one of camaraderie but of love. How to call by any other name that obsessive attraction, that fascination, to which in those first days I surrendered myself with delight?” The young Maumort follows Guy from room to room “like a dog. … I did not tire of touching his clothes, his toiletries; everything that belonged to him was endowed with magical virtues. I watched him come, go, get up, sit down, with inexhaustible rapture.” Even granting that the prose here may be overwrought, du Gard makes it clear that what fascinates the young Maumort so much about Guy is that he’s completely unashamed about his body, even to the point of performing naked handstands right in front of him. What’s more, it soon becomes apparent that Guy is having an affair with their childhood tutor, Xavier (more on this later as well). As if anticipating the reader’s reaction, du Gard writes: “I feel no embarrassment at elaborating on all these psycho-sexual details; I even mean to linger over them at leisure, with a total candor and an assiduous accuracy. When one approaches the domain of sexuality, one must not be stingy with personal confidences. … Tell me what your puberty was like, and I will tell you who you are.” And make no mistake: these early encounters are fully and vividly delineated. Upon entering boarding school, Maumort meets a fellow student named Luzac, and they begin the frequent habit of masturbating each other in secret in German class, protected from view by a shielding desk:

One day I felt his hand hunting for the opening of my pocket and sliding between my thigh and the cloth of my trousers. … I felt his fingers come near and take hold of me. From then on, this more direct fondling became a new habit, and I let it happen without attempting to defend myself. … I had his bare and moist hand on my belly. … He ran his caressing hand over me softly, tenderly, taking a slow, passionate and meticulous inventory of my most intimate treasures, and the expert gentleness with which he handled me produced a sudden spasm.

Before long, Maumort begins to reciprocate, and “From then on, I got used to turning my eyes stealthily towards him at the moment I was watching for his spasm, and I would revel in the sight of his ravished, somber, almost pained face.” Considering the frequency and intensity of these experiences, it comes as something of a shock when, some time later, Maumort states: “As far as I am concerned, I think I can state that my erotic obsessions were, at the time, directed exclusively towards women.” Whether du Gard himself was gay is still an open question, but, given his close friendship with Gide, one can deduce that he had no objection to being gay. Intriguingly, as embodied in the character of Maumort, we get the sense of an author trying to answer the question of how, when one has sex with other men, one does not turn out to be homosexual. To wit, what is one to make of the following passage?

[A]t that time—the time when I was beginning my studies at the Sorbonne—I had no notion of the role that homosexuality plays in society. The games of two boys seemed to me a stop-gap due to the absence of the female sex. … I did not imagine that those games could continue among adults, or that a grown man … would, out of personal taste, go looking for other men. … And, in any case—of this I am certain—I had no idea what homosexual love was. I mean I was not aware that relations between men could be anything other than a joint exercise in onanism.

This gives rise to the question: if, later in life, du Gard as Maumort has somehow come to understand what homosexual love is, how has he arrived at this understanding? As the translators remark in their introduction: “To what extent does Maumort’s memoir constitute a disguised confession by Martin du Gard? We can only speculate.” But I have yet to address the most remarkable gay-positive aspect of the book, a chapter called “The Drowning” that purports to be an entry in the diary of Maumort’s childhood tutor Xavier. It tells the thinly veiled story of a young military recruit posted in rural France who becomes enamored of a local youth. Through a series of secret meetings, they realize their mutual attraction. There is an eventual confirmation of this on both sides, which leads to tragic consequences. So nuanced and sensitive is the description of this attraction, so painstakingly detailed are the perils of the romance, that one is again left wondering why a straight man would feel compelled to create a fifty-page gay love story, and how he could do it so successfully without a huge amount of sympathy or fellow-feeling himself. Lieutenant-Colonel de Maumort is beautifully written and psychologically astute, and it contains an almost romantic depiction of a vanished world. Indeed, in an earlier conception of the work, Maumort locks himself in the bedroom of his chateau as the Nazis invade, intent upon chronicling the era rapidly vanishing all around him. Though the comparisons to Tolstoy seem to me a stretch, the parallels to Proust are entirely appropriate. Indeed, the depictions of the salons of his parents, in which characters such as Pasteur and Turgenev wander through, are very reminiscent of Madame Verdurin’s soirées in In Search of Lost Time. Alas, the novel–memoir breaks down after 500 or so pages and is ultimately incomplete. There are also some painfully racist scenes (again, one isn’t sure whether to blame Maumort or du Gard). Du Gard’s indecision on the book’s genre takes a toll. It does not seem to me that his later attempt to recast the work as a diary, or as an epistolary novel (which is also included in the volume), succeeds any better than the early novelized memoir. Nevertheless, as imperfect and incomplete as it is (like life itself), Lieutenant-Colonel de Maumort still delights and astonishes, and it deserves to be much better known.

Dale Boyer, a frequent reviewer in these pages, is the author of Columbus in the New World: Selected Poems.