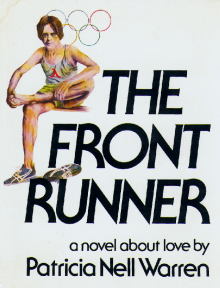

IT WAS IN 1974 that Patricia Nell Warren (1936-2019) submitted a manuscript about a gay love story to her agent of record John Hawkins at Paul Reynolds Inc. A week later, William Morrow and Co. bought the English-language publishing rights for $7,500 (considered a standard advance for a first novel). Jim Landis was the editor in charge. He punched up the narrative pace but requested no changes for sexual content. “This is a subject whose time has come,” he said.

The Front Runner told the story of Billy, a 22-year-old distance runner who falls in love with his coach Harlan and participates in the 1976 Olympic Games in Montreal (anticipated by two years). Billy wins the 10,000-meter race; one week later, at the 5,000-meter race, as Billy pulls away in his finishing sprint to win the gold medal and set a new world record, tragedy strikes. But that’s not the whole story.

Before the Games, Billy and Harlan had sealed their love with a commitment ceremony. In the words of the novel’s narrator, Harlan Brown: “We saw it simply as a formal public declaration of our love for each other, of our belief in the beauty and worth of this love, of our intention to live together openly, of our rejection of heterosexuality. Neither of us was a blushing bride led to the altar. Neither of us was bound to obey, or to be the property of the other. We were two men, male in every sense of the word, and free.” This was unprecedented in 1974, as was the idea of a gay Olympian who has no issues with his sexuality, studying at a welcoming college campus on which Billy and a teammate set up a gay studies program.

Warren was inundated with fan mail, and the gist can be summed up in a few words: “Your book changed my life.” Book sales were in the millions, and clearly that included many non-gay readers as well as gay ones. While not the first explicitly gay novel (for example, Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar came out in 1948), The Front Runner was the first to attract a mainstream audience. A year later, there was already talk of making it into a movie—Paul Newman signed a contract to produce and star in it—but that never materialized. In The Celluloid Closet, Vito Russo called it “the most celebrated failure to produce a film from gay fiction.” To this day, Warren’s estate is still working on bringing The Front Runner to the silver screen.

Soon after its publication, The Front Runner began to inspire the formation of gay running groups worldwide. A San Francisco team simply used the book’s title as their name, and the Frontrunners was born. They bravely published a membership directory and joined the Amateur Athletic Union. Soon the name spread across the country (spelled variously as “Front Runners,” “Frontrunners,” or “FrontRunners”) and around the globe. Their multilingual website (at frontrunners.org) lists gay and lesbian sports events, offers links to Frontrunner clubs worldwide (with over 100 in the U.S., Europe, Australia, and other countries), and states its mission thus: “Each club is a place to run for fun or fitness, a place to compete or not compete, a place to brunch, a place to look for a lover, a safe place to meet and be with spirited gays and lesbians of wide diversity and a place to find or be oneself.” Now there are even Front Walkers and Front Wheelers, a less strenuous but equally valid way to stay in shape and show one’s pride.

A measure of The Front Runner’s cultural reach is that it has made its way into other works of gay literature. In Tales of the City, author Armistead Maupin credits The Front Runner with starting the craze for wearing running shoes when clubbing. In Felice Picano’s Like People in History (1995), a tipsy group of gay and straight friends piles on a list of famous celebrities they have met, when one of them interrupts: “[You] did not meet Patricia Nell Warren.” In Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic (2006), The Front Runner is among the coming-out books that’s read by the protagonist. Eyewitnesses reported that Marlene Dietrich got out of a black limousine in front of A Different Light bookstore in West Hollywood and purchased a copy.

Fifty years later, The Front Runner remains relevant for several reasons. This year, Paris hosts the thirty-third Olympic Games. A record number of LGBT athletes is expected to compete, more than in Tokyo in 2021 or in Rio in 2016. Warren can be credited with paving the way for them. In 2006, when the World Outgames were held in Montreal, Warren was honored with running the last lap of the men’s 5,000-meter race, a tribute to her trailblazing role in combating homophobia in athletics. In 2012, The Front Runner was recognized as instrumental in inspiring the launch of the Gay Games, and Warren was awarded a special “Personal Best” and gold medal by the International Federation of Gay Games.

Another reason The Front Runner remains timely is that it anticipated what today is a veritable explosion of romantic gay literature. This element in the novel—the idea of two gay men in a loving relationship—came in for considerable criticism in the 1970s. Today, it seems visionary. Casey McQuiston’s Red, White, & Royal Blue, Alice Oseman’s Heartstopper, Becky Albertalli’s Simon vs. The Homo Sapiens Agenda, and Benjamin Alire Sáenz’ Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe are some of the most famous examples.

Finally, there may be another reason why The Front Runner still matters. Things suddenly seem less rosy for queer people in the U.S. Warren’s gay-positive novels from the 1970s, of which there were two more—The Fancy Dancer dealt with homosexuality in the Catholic church, and The Beauty Queen addressed Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” crusade—remain vital reminders of the need for courage in the face of anti-gay oppression.

Nikolai Endres, a professor of world litera-ture at Western Kentucky University, is the author of the forthcoming Patricia Nell Warren: A Front Runner’s Life and Works,.