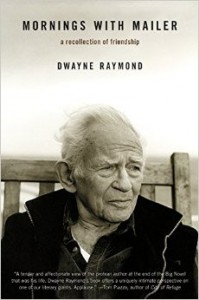

Mornings with Mailer: A Recollection of Friendship

Mornings with Mailer: A Recollection of Friendship

by Dwayne Raymond

Harper Perennial. 352 pages, $13.99

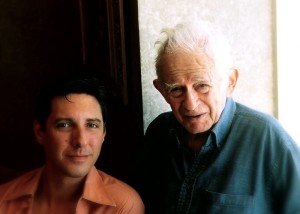

WHAT DOES a gay waiter with a soon-to-be transgendered lover have in common with an über-heterosexual writer? Well, as Dwayne Raymond points out in his accomplished memoir Mornings with Mailer, a lot more than one would think. Raymond had given up on writing and was currently a waiter in Provincetown, where the prolific author Norman Mailer (forty books, two Pulitzers, and a National Book Award) had gone to live, when in April 2003 Mailer picked him, after just a few brief encounters, to be his researcher. While Raymond remains puzzled at his selection, the impulsive act is typical of a person who had an astute sensitivity to human nature. When Mailer and I met for the first time in 1975 he told me after just five minutes, “I like you. We will be friends for life.” He kept his word and we were in close contact until his death in November 2007.

As it turns out, his choice of Raymond could not have been more inspired. Few people could have tolerated the mood swings of a man as notorious as Mailer was for a protean temperament. And he had his fair share of phobias—television, computers, and plastic, to name but a few—and lifelong habits that did not bend easily to new situations. But Raymond was clearly up to the task. Initially in awe of the famous writer, his daily interactions soon took on a different dimension. Within a short time, he became literally chief cook and bottle washer, tending to Mailer’s every need.

At turns charming yet stubborn, irascible yet honest, demanding yet humorous, Mailer can sometimes be as hard to love as he is to resist. Raymond is very honest on both counts. Their rare contretemps add a pinch of spice to a book that could easily have descended into sentimentality. Ultimately, Raymond is one of those fortunate souls who stumbled into a job for which he felt unqualified only to find himself in the midst of a life-transforming situation.

Woven into the narrative is Raymond’s own story as a gay man. For Mailer, Raymond’s homosexuality was never an issue. (After all, he did live in Provincetown!) I can also attest to this, receiving a most warm note when I came out to him a few years after we met, proving once again that heterosexual men who are secure in their identity are not the ones who have a problem with gay men. Mailer’s sensitivity to human nature helped Raymond in his sometimes troubled relationship with his lover Thomas, who worked intermittently as a handyman at the Mailer home. It was Mailer who detected the underlying cause for their problems long before Thomas revealed that he wanted a sex change. Mailer was unfazed by this situation, too, lending credence to a remark by one of Mailer’s friends that in matters of sexuality, he was “so much more advanced” than most people.

Woven into the narrative is Raymond’s own story as a gay man. For Mailer, Raymond’s homosexuality was never an issue. (After all, he did live in Provincetown!) I can also attest to this, receiving a most warm note when I came out to him a few years after we met, proving once again that heterosexual men who are secure in their identity are not the ones who have a problem with gay men. Mailer’s sensitivity to human nature helped Raymond in his sometimes troubled relationship with his lover Thomas, who worked intermittently as a handyman at the Mailer home. It was Mailer who detected the underlying cause for their problems long before Thomas revealed that he wanted a sex change. Mailer was unfazed by this situation, too, lending credence to a remark by one of Mailer’s friends that in matters of sexuality, he was “so much more advanced” than most people.

Raymond eventually became a trusted and reliable member of the family, developing an especially warm relationship with Norris, Mailer’s wife, a charming beauty, artist, and writer in her own right. (Her recently published memoir A Ticket to the Circus serves as a nice companion to Raymond’s book.) Far from a fawning puff piece, Mornings with Mailer shows the writer “warts and all” and functions in many ways as a kind of stealth biography, touching on many of Mailer’s works and also his familial relationships. The section devoted to his work habits, especially the years of research that went into producing his final work, The Castle in the Forest (2007) dealing with Hitler’s genealogy, is a revelation—and probably humbling for most would-be novelists. As a writer, Raymond himself has a keen eye and a deft ability to capture in a few short sentences the essence of the numerous friends, some famous and some not, who pop in and out of Mailer’s life.

Mailer had an image and reputation that were often at odds with the real person, and this book does much to rectify many common misconceptions. At the same time, Raymond does not beat the gay drum too loudly, allowing for events rather than an agenda to make his case about Mailer’s tolerance, a matter that this book puts safely to rest.

By the time of Mailer’s death, it’s obvious that Raymond has fallen completely under the thrall of Mailer, finding in him a father figure and also a role model for a life devoted to art. The pages detailing the final weeks of Mailer’s life and the scene at his deathbed make for very moving reading, only assuaged by the celebration of his life that follows.

Mashey Bernstein teaches in the Writing Program at the University of California and has written numerous articles on Mailer and his work.