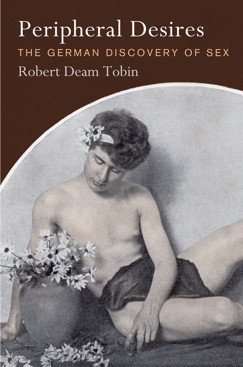

Peripheral Desires: The German Discovery of Sex

Peripheral Desires: The German Discovery of Sex

by Robert Deam Tobin

University of Pennsylvania Press

326 pages, $69.95

BACKGROUND IN A NUTSHELL: the dark ages for gay men began in the 4th century CE, when Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire. A taboo carried forward from the Holiness Code of Leviticus imposed the death penalty for sex between males. Male love went underground, though men never ceased to love and have sex with each other. For centuries, male lovers suffered dishonor, imprisonment, torture, and death. With the Renaissance, the rebirth of classical antiquity, homoerotic themes began to reappear in art and literature. Then the philosophers of the 18th century Enlightenment brought a secular approach to matters of morality, and extended free inquiry to the nameless sin.

The first known written arguments for abolishing sodomy statutes (a generic term for any laws that criminalize sex between males) were made in the late 18th century by the philosopher Jeremy Bentham, who argued—brilliantly and comprehensively—that all-male sexual acts were not harmful and should not be punished. However, these writings were not published until nearly two centuries later (“Offenses Against One’s Self: Paederasty,” written circa 1785, first published in 1978).

In 1818, Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote an essay, “A Discourse on the Manners of the Antient [sic]Greeks relative to the subject of Love,” to accompany his translation of Plato’s Symposium, which would have been the first in English to present the genders correctly. Unfortunately, Shelley’s widow Mary suppressed and bowdlerized both the translation and the essay, which were not published as written for well over a century.

Later in the 19th century, the first open polemics would be published, and in 1897 the first activist organization would be founded. This brings us to the recently published Peripheral Desires: The German Discovery of Sex, by Robert Deam Tobin, Professor of German at Clark University. This is by no means the first book to cover the early homosexual emancipation movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Indeed, I believe that honor falls to David Thorstad and me for our book, The Early Homosexual Rights Movement (1864-1935), which was published in 1974.

But Tobin has a new approach. He describes his book as ultimately “about a history of ideas—ideas that would one day have a concrete force in people’s lives, although they may have been obscure at the time of their emergence.” In his Preface, Tobin describes two competing paradigms:

Much of the scientific research on sexual orientation continues to work on the assumption that homosexuals constitute a discrete minority, with biologically identifiable characteristics that often have something to do with gender inversion; this research typically claims to be part of a liberal political agenda. At the same time, a counter-discourse persists, according to which most people are bisexual and capable of strong erotic and emotional bonds with members of their own sex, even if they typically favor heterosexual liaisons.

Tobin indicates up front that Peripheral Desires will focus “almost entirely on men.” Although his book covers a lot of historical and political ground, I’ll concentrate on his primary thesis that sexual categories formulated in the 19th century have carried forward into the present.

First, a word about terminology: in order to avoid anachronism, Tobin chooses to use the nomenclature employed by the authors he studies—“urning,” “invert,” “homosexual,” or whatever. That’s fine, if occasionally awkward, but I myself will also use the word “gay” as sometimes the best and even least anachronistic term. (Rictor Norton in 1997’s Myth of the Modern Homosexual has demonstrated that by the time of Byron and Shelley “gay” was already used underground in its present sense.)

In the year 1869 three writers addressed in German the topic of same-sex relations: the Latinist, lawyer, and independent scholar Karl Heinrich Ulrichs; the journalist Karl-Maria Kertbeny; and the physician Karl Friedrich Otto Westphal. Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, regarded as the grandfather of gay liberation, began in 1864 to issue a series of “social and juridical studies on the riddle of love between males.” He coined the term “Urning” (“Uranian” in English) to represent what he believed was a rare variety of human male, a lusus naturae (sport of nature), an anomaly characterized by the formulation “anima muliebris corpore virili inclusa” (a female soul trapped in a male body). Urning is based on a speech in Plato’s Symposium in which Pausanias postulates that there are two gods of love: Uranian (Heavenly) Eros, who governs principled male love, and Pandemian (Vulgar) Eros, who governs heterosexual or purely licentious relations. For Ulrichs, a Uranian might look male enough, but psychologically he was female. The German-Hungarian writer Karl-Maria Kertbeny wrote two pamphlets in 1869, published anonymously, which demanded that sexual acts between males be freed from criminal sanctions. He was the first to use the word “homosexuality” (German “Homosexualität”) for both male and female same-sex intercourse. Although etymologically and conceptually unsound, the new coinage was soon appropriated by medical writers, who used it to denote an abnormal condition of being attracted to one’s own sex, or not attracted to the opposite sex, or both. The German physician Karl Friedrich Otto Westphal coined the expression “die contraire Sexualempfinding” (contrary sexual feeling) to apply to a lesbian and a male transvestite under his observation. The part-French, part-German term was awkward, and in time it evolved into “sexual inversion.” Westphal considered the condition to be an incurable neurological or psychological disease. In Tobin’s words: “Whereas Ulrichs and Kertbeny present a relatively positive picture of the urning and the homosexual, Westphal’s invert is quite clearly sick. … He believes this love is pathological to its core.” Tobin shows that despite their differences, all three—Ulrichs, Kertbeny, and Westphal—regarded the “fixed sexual attraction to men” as an inborn, unchangeable condition found only in a small minority of males. “All three see men who love men and women who love women as belonging to the same overarching category.” Both Ulrichs and Westphal, though not Kertbeny, “emphasize gender inversion as the explanation for sexual attraction between members of the same sex.” By the end of the 19th century, the terms originated by these men—Uranian, homosexual, and invert—became nearly synonyms, used interchangeably in medical and polemical literature. But to backtrack three decades, Tobin’s first chapter is devoted to Heinrich Hössli, a Swiss who published the first major polemic for the emancipation of male love, a two-volume work titled Eros: The Male Love of the Greeks, Its Relationship to History, Education, Literature, and Legislation of All Times (1836 and 1838). Making his case with a wealth of classical literature, as well as Persian, Arabic, and Turkish poetry, Hössli argued that male love was not a phantasy, a monstrosity, or a rare exception, but rather a universal human desire. Tobin’s chapter on Hössli provides much valuable information on a neglected figure in the history of our movement. Hössli vehemently compared the medieval persecution of alleged witches to the persecution of males who loved each other. It’s hard to tell how much influence Hössli’s work had, and such influence would have been largely underground—which opens up a possibility I’ve pondered for some time: the possibility that for ages, centuries even, there has existed an underground of gay scholars, ranging from medieval writers through Marlowe, Bentham, Shelley, Hössli, Ulrichs, John Addington Symonds, Richard Burton, and Edward Carpenter. Tobin sums up Hössli’s work like this: “[Hössli] reorganized the intellectual givens of his time to put forth one of the first comprehensive visions of an identity based on same-sex sexual love that was inborn, natural, unchanging, essential, universal, ahistorical, and in need of some sort of social protection.” Ulrichs was inspired by a passage in Hössli, which quoted an article in a Munich newspaper that discussed the Kabbalistic belief in the transmigration of souls, according to which a female soul might end up in a male body. The Kabbalistic belief is that gendered souls, between reincarnations, are floating around, waiting to occupy bodies. Once in a while a female soul mistakenly ends up in a male body, resulting in a male invert, who is attracted only to other males. Hössli himself rejected this notion, arguing that some lovers of other males had quite masculine souls. But Ulrichs embraced the notion, from which he developed his key formulation concerning gay men: “a female soul trapped in a male body.” Even today, the core transsexual credo is not too far from this medieval notion. Hirschfeld and Friedlaender Next on the scene was Magnus Hirschfeld, who in 1897 cofounded the world’s first activist homosexual rights organization, the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee. Although Tobin discusses him only briefly, Hirschfeld was in fact the leading figure in the international movement for sexual reform and homosexual rights for over three decades. Hirschfeld carried the ideas of Ulrichs even further, maintaining that the bodies as well as the psyches of homosexuals were sexually intermediate. Hirschfeld called homosexuals “sexual intergrades” or a “third sex,” and lumped them together with transvestites and “pseudo-hermaphrodites” (people with ambiguous genitalia). We may admire Hirschfeld for his courage and energy, but many of the ideas with which he saddled the new movement were appalling. Opposition to the gender-inversion model was not long in coming, and it came from men that Tobin calls “masculinists.” The masculinists greatly admired ancient Greece and its celebration of male-male love. Tobin treats the two opposing camps—the inversionists and the masculinists—evenhandedly, which is his privilege and perhaps best for the purposes of his book. My own sympathies lie with the so-called masculinists, and I write accordingly. The leading masculinist was Adolf Brand, who published Der Eigene, the oldest journal devoted to gay love, some of whose issues were beautifully produced. A married man himself, Brand espoused bisexuality and followed the libertarian anarchist principles of Max Stirner (The Ego and His Own, 1844). In 1903 Brand founded the Gemeinschaft der Eigenen, which can be translated in many ways, from Community of the Special to Community of Self-Owners. I now choose to translate it as Community of One’s Own or perhaps even Community of Self-Possessed Men. (There were no women in the group.) One of the first rebuttals to the inversionists came in a 1900 anthology by the artist Elisàr von Kupffer, whose title translates roughly as “The Chivalrous Love of Young Men and the Love of Friends in World Literature.” In a prefatory essay, Kupffer ridicules the notion of “a third sex, whose soul and body are supposed to be incompatible with each other,” and comments that the geniuses and heroes of ancient Greece could “hardly be recognized in their Uranian petticoats.” He writes: “At this point it is morally obligatory to let a ray of sunshine from the reality of our historical development fall on all this blather about sickness, on all this muck of lies and filth.” Von Kupffer considered the freeing of male love to be part of the “emancipation of man for the revival of a manly culture.” He discussed the word “masculine,” which for him was not just the rougher qualities, but also an appreciation of male beauty and “preserving self-determination, personal freedom, and the common good.” Hirschfeld’s most formidable opponent was Benedict Friedlaender, a supporter of the Gemeinschaft der Eigenen, a scientist, a married man, and the father of two sons. In 1907 he led a split from the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee. In a position paper addressed to the friends and supporters of the Committee, he ridiculed the Ulrichs-Hirschfeld notion of the third sex and of “a poor womanly soul languishing away in a man’s body.” Friedlaender insisted that a truly scientific approach must take into account the facts of history and anthropology. In two sentences he annihilated the Hirschfeld position: “A glance at the cultures before and outside of Christendom suffices to show the complete untenability of the ‘intermediate types’ theory. Especially in ancient Greece, most of the military leaders, artists and thinkers would have had to be ‘psychic hermaphrodites.’” Friedlaender believed that members of the medical profession were overly prominent in the homosexual rights movement, giving the impression that the movement was concerned with some kind of disease or sickness. He considered “physiological friendship” to be an instinct present in all men—the basis of sociality—something of great value to society and to the individual. He believed that the great majority of men—especially married men—could and ought to experience male love. In one passage, Friedlaender argued that such words as “atheist” or “Urning” can be used as put-downs just by labeling someone as an exception or peculiarity. He turns the tables on straight men by coining the word “Kümmerling,” referring to a stunted growth, like the suckers that grow on tree trunks: “By ‘Kümmerling’ or ‘moral Kümmerling’ I mean those men whose capacity for Lieblingminne [love of young men]has been artificially crippled through moral pressure in the same way as the feet of Chinese women have been crippled through the mechanical pressure of instruments of bodily constraint.” In this analysis, what’s “queer” is to be completely straight. Throughout his writings Friedlaender insists that loving men is a fully masculine characteristic. Although he was a scientist, he didn’t hesitate to use the word “love,” and he argued that one cannot make sharp distinctions among sex, love, and friendship, which are different expressions of the same thing. If Friedlaender was appalled by Hirschfeld’s ideas, the latter was horrified by Friedlaender’s, and he wrote that his opponent’s bisexuality and Kümmerling theories were furnishing “water for the mill of the enemy.” However, Hirschfeld did eventually respond to criticism, and by 1910 his “sexual intergrades” and “third sex” theories had pretty well fallen by the wayside. The masculinists favored the scientific approach inasmuch as they backed up their arguments with evidence. Friedlaender began a section in his position paper by writing: “Now, what exactly is the science of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee?”—and then proceeded to demolish Hirschfeld’s “third sex” theories. Throughout the writings of Friedlaender and other masculinists are attacks on superstition, priests, and clerics. I think Tobin slights the role of religion in the condemnation of sex between males. In the very first Yearbook (1899), Eugen Wilhelm contributed a fifty-page history of laws that punish homosexual acts. He begins thus: “In Asia only the Jews seem to have had a penal provision against same-sex intercourse, and indeed they punished it with death.” In the third book of Moses, God instructs: “You must not lie with boys as with women, for that is an abomination” and “Then whosoever commits such an abomination, their souls will be rooted out from their people.” In the following chapter, it is commanded: “If someone sleeps with a boy, as with a woman, he has committed an abomination, and both of them shall be put to death, their blood is upon them.” Wilhelm proceeds to quote the relevant passages from Leviticus and Deuteronomy. A fold-out triptych published in the fifth Yearbook (volume I, 1903) amusingly illustrates the Third Sex theory. The overall title is: “Ratio Between the Hips and the Shoulders.” The man on the left, leaning on a pedestal, holding a fig leaf over his genitals, is labeled “manly type”: he has narrow hips and wide shoulders. The creature in the middle, masked, his membrum virile tucked between his flabby thighs, is labeled “Uranian type”: his hips and shoulders are of equal width. The woman on the right (a painting) is labeled “womanly type”: her hips are much wider than her shoulders. Well now, if anyone in this triptych is gay, it is the butch number on the left. I can imagine what he would be like in bed; he’d eat a big breakfast in the morning and say “thank you” as he left. Who knows what the interests of the Uranian type would be? A New Look Back—and Forward Besides the opposition between inversionists and masculinists, Peripheral Desires covers a lot of ground: colonialism, national politics and identity in the 19th century, and the emancipation of women. One chapter discusses a novel by Arnold Zweig, based on a real case involving the murder of a man living in Palestine before Israel was founded. He was both a pederast and an ultra-orthodox Jew. At first it was “assumed he was the victim of an Arab family whose honor had been outraged by [his]predilection for young Arab males.” It turned out that his real murderers were Zionists who were opposed to his policies. In a fascinating chapter called “Thomas Mann’s Erotic Irony: The Dialectics of Sexuality in Venice,” Tobin analyzes Death in Venice. Mann, who was sexually conflicted, subjects the ideas of the protagonist, Gustav von Aschenbach, to hostile scrutiny through the voice of the narrator. Greek love, as fancied by Aschenbach, leads in real life to death and decay, thus refuting the ideas of the masculinists. Far from being a gay classic, as is often assumed, the novel is insidiously hostile to male love. Tobin is not sympathetic to those who “relied on the ancient Greek tradition, projecting same-sex desire on to the Hellenic world.” Peripheral Desires is filled with snide comments on Greece and its admirers. Speaking as a gay Hellenist myself, I unashamedly consider ancient Greece the spiritual homeland for gay men; I believe in the Greek Miracle: that the finest aspects of Western Civilization developed in Athens. It is not necessary to project male love on to the Hellenic world. Male love was abundantly there, enthusiastically celebrated in art and literature. Tobin neglects to mention Paul Brandt, who wrote under the pseudonym Hans Licht. A formidable Classical scholar, Licht wrote for the Yearbook and contributed a superb article, “Homosexuality in Classical Antiquity,” to Magnus Hirschfeld’s The Homosexuality of Men and Women (1914). This suggests that by 1914 Hirschfeld was not hostile to the Grecophile arguments of the masculinists. Tobin also does not mention Kurt Hiller, who was a leading activist in the early homosexual rights movement and a leading advocate for minority rights. Hiller’s 1928 speech, “Appeal to the Second International Congress for Sexual Reform on Behalf of an Oppressed Human Variety,” reflects the minoritizing views of the inversionists, but also the masculinist view that homosexual men could be robustly healthy and virile. After ranging far afield for much of the book, Tobin brings his primary theme home in the last chapter, “Conclusion: American Legacies of the German Discovery of Sex,” to show that the notions of the inversionists are still with us, and indeed prevail in many areas. He refers to decisions by the Supreme Court and the policies of other branches of the U.S. government: “According to this view, sexual orientation is innate and universal, a biological constant. The government puts its full weight behind a growing consensus that sexual orientation is analogous to gender and homosexuals form a discrete minority comparable to racial and ethnic minorities—a set of beliefs first articulated by thinkers like Hössli, Ulrichs, and Kertbeny.” Tobin refers to seriously flawed research by Simon LeVay and Nicholas Wade, which purportedly shows that homosexuals are physically as well as psychologically between male and female heterosexuals: “Research on same-sex desire continues to conflate transsexuality with same-sex desire, assuming that male desire for men is essentially the product of a feminine (or at least nonmasculine) brain in a male body.” Concludes Tobin: Debates that emerged in nineteenth-century German-speaking central Europe still structure discussions today. On the one hand, [the inversionists,]a modern, minoritizing, biologically based, liberal model of sexual orientation stands as a category comparable to gender and race. On the other hand, [the masculinists,]a model of a widespread, fluid, classically oriented, majoritizing, culturally based, aesthetically focused desire for members of one’s own sex persists. “Culturally based” is the only thing I dissent from here. While the masculinists saw that cultural factors determined the acceptance or condemnation of male love or Lieblingminne, they also saw that the capacity for such love is inborn in human males—and in virtually all males, not just a small minority. In modern terms, homoeroticism is a phylogenetic characteristic of the human male. Except for a few unfortunate Kümmerlings, all males are at least potentially gay. References Friedlaender, Benedict. Die Liebe Platons im Lichte der modernen Biologie. Berlin 1905. Hirschfeld, Magnus. The Homosexuality of Men and Women. Translated from the German by Michael A. Lombardi-Nash. Amherst, New York 2000. (Originally published in German in 1914; second edition 1919.) Licht, Hans (Paul Brandt). Sittengeschichte Griechenlands. Dresden/Zürich 1925-28. (Bowdlerized translation as Sexual Life in Ancient Greece, 1932.) Shelley, Percy Bysshe. “A Discourse on the Manners of the Antient Greeks Relative to the Subject of Love.” (Written in 1818, published in 1931.) John Lauritsen’s recent books include The Man Who Wrote Frankenstein and (as editor) Aeschylus’ plays as translated by Percy Bysshe Shelley and Thomas Medwin.

Ulrichs, Kertbeny, and Westphal