Francis Bacon in Your Blood

Francis Bacon in Your Blood

by Michael Peppiatt

Bloomsbury. 401 pages, $30.

ONE OF THE THINGS we learn from critic Michael Peppiatt’s memoir of his decades-long friendship with the British painter Francis Bacon is that the way Bacon met his lover George Dyer in the 1998 film Love Is the Devil is not how it happened in real life. In the movie, they meet when Dyer (played by Daniel Craig) comes crashing through the skylight of Bacon’s (Derek Jacobi) studio during a robbery attempt. In fact, Bacon tells Peppiatt in Francis Bacon in Your Blood, Dyer simply saw the painter and his pals in a club in London and introduced himself, because they seemed to be having a good time.

A good time is only one way to describe what Bacon called “the sort of gilded gutter life” he lived, “constantly surrounded by nothing but drunks, layabouts and crooks”—i.e., the regulars at the Colony Room, a legendary SoHo dive that Bacon favored. The doyenne of the Colony Room, a lesbian named Muriel Belcher, never let the man she liked to call her “daughter” think too much of himself. In one scene, when someone refers to the painter as a superstar, she snaps, “You’re not a superstar, dear, you’re just a cunt.” “Well, I suppose I am,” Francis replies, almost gratefully. “If you say so.” Upon which another habitué has the final word: “I don’t care who calls who what. We’d all be better off dead. The whole lot of us.”

The Colony Room was a Joe Orton play come to life. The put-downs and teasing are cruel and hilarious. Death, Bacon tells Peppiatt, is what it’s all about. But meanwhile, “we might as well be as brilliant as we can be.” Bacon’s paintings had indeed made him a superstar by the time Peppiatt, an undergraduate at Cambridge trying to edit an arts magazine, came to London to interview him. But this did not prevent another of the barflies from telling Bacon to his face: “You’re a pig in name and a pig in nature,” which doesn’t bother him at all. As Bacon puts it: “I always think of real friendship as where two people can tear each other to pieces.”

What was it about postwar England that produced Joe Orton, the Angry Young Men, the Kray Twins, Kingsley Amis, Philip Larkin, Brutalist architecture, and Francis Bacon? Bacon, who read Nietzsche when he was a young layabout himself, had a rather dark world view, fueled by considerable alcohol consumption. “Well, this is my life,” he says, sipping cognac. “From bar to bar, person to person.” Peppiatt’s book is based on what used to be called table-talk—though here, bar, pub, studio or restaurant might be a better prefix. As the years pass Peppiatt realizes that Bacon says the same things over and over, so that he doesn’t have to write them down—they will be repeated—though he goes back after their bar crawls and records them anyway, just as Boswell copied down Samuel Johnson’s conversation. His memories, recalled here in the present tense, are an ongoing notation of not only what Bacon said but what wines were consumed, which ones sent back, which ones spat out—which makes his book an oenophile’s delight.

There’s also whiskey, cognac, and champagne. “Champagne for my real friends, real pain for my sham friends!” Bacon cries when he buys yet another round. “I myself always want the best of everything for myself and for my friends. I want the best food and the best wine I can get as well as the most excitement and the most interesting people around.” And he’s got the money to have all that. By the time Peppiatt shows up, Bacon’s paintings are selling for enormous sums (and still are—in 2013 a Bacon painting sold at auction for a record $142.4 million). It’s money Bacon spends as fast as it comes in, not only tipping extravagantly, treating people to drinks and dinners, but offering to help Peppiatt out the minute a hint of need arises—something at which Peppiatt draws the line, though help is given nonetheless in other ways.

Indeed, this memoir is really the story of how the narrator eventually finds his place in the world with Bacon’s help. “Listen, Michael,” the painter says at the outset, “you’ve got looks, you’ve got charm and you’ve got intelligence. Your life’s only just beginning, you’ve got everything before you. You can go anywhere and have anyone you want.” Peppiatt sees himself quite differently: as “an obscure young man filled with self-doubt and painfully adrift in the universe.” Or, as Sonia Orwell puts it, when Bacon urges her to include the Cambridge student in a dinner party: “Well, I suppose you can come if you think you’ll fit in, but I should warn you you’ll be out of your depth intellectually, and probably socially.” Bacon doesn’t see it that way. His advice to his young friend, when Peppiatt, still in school, doesn’t know what he wants to be, is simple: “Drift and see.” And that’s just what Peppiatt does—in Bacon’s glittering wake. He ends up not only going to the dinner party but having sex with Sonia Orwell while her former lover, Cyril Connolly, paces up and down in the corridor outside. And he will go on to write at least five books on Bacon, along with others on Giacometti, Miró, and other artists.

Peppiatt is drawn to homosexuals, which makes him wonder about himself; but in Barcelona, when he gives it a try and lets a man kiss him on the mouth, he is so revolted that he jumps up and runs out of the apartment. In fact, for Bacon, part of Peppiatt’s attraction is that he’s straight—a straight man who is waiting to be “turned.” “I think there are a great many men who don’t really know what they are sexually,” says Bacon. “Often of course they’re neither one thing nor the other. And then some of them who are really homosexual simply can’t accept it. They probably think it’s not manly or something.”

But in Peppiatt’s case this never happens. Something else happens instead: Bacon becomes for Peppiatt a father figure. Estranged from his own father—a difficult manic-depressive—the young drifter is the perfect audience for Bacon’s bleakness. Indeed, quotes cannot convey the theatrical magnetism of Bacon’s mono-logs, the black humor that makes one think of an English drawing room comedy set in an abattoir, but Peppiatt is mesmerized. Among the aphorisms: “We all live off one another. You have only to look at the chop on your plate to see that.” “We go from nothing to nothing.” “Life’s a charade.” And: “We’re all on our way to becoming dead meat. … And that’s all there is.”

Death and disaster are always in the wings in Bacon’s universe—summoned up with the sort of wit Mary McCarthy once called in an essay on Oscar Wilde “the comedy of heartlessness.” On encountering plastic flowers in a Parisian salon, Bacon hisses: “Why can’t she have real flowers? The whole point of flowers it that they die.” On his closest sibling: “My sister Winnie … had one catastrophe after another, even before she developed multiple sclerosis. She only had to get on a train for it to burst into flames.” On being told a man has just murdered his girlfriend and then turned the gun on himself: “Well, I suppose it’s a gesture. But it’s a gesture one can make only once.” And then there’s the horrified waiter in a Parisian restaurant the night Bacon wrests the bottle of wine from him and empties it into his friends’ glasses. “But Monsieur,” the waiter says, “those are the dregs.” “But I love the dregs,” Bacon replies, beaming up at him. “The dregs are what I prefer.”

And then there’s the suicide of George Dyer on the very day that Bacon is receiving accolades at the opening of a retrospective of his work at the Grand Palais. Again one thinks of Joe Orton—whose lover Kenneth Halliwell bashed Orton’s head in with a hammer the day before Orton would go off in a limousine to work on a screenplay for the Beatles. Both Halliwell and Dyer sensed they were losing lovers who were far more successful than they. Dyer had entered Bacon’s life as an East End tough but proved to be far less powerful than the homosexual who took him in. “He didn’t know who he was,” Bacon tells Peppiatt. “Most men never do.” Dyer was trying to drink himself to death—though the suicide involved pills as well. After that Bacon acquired another companion from the East End, John Edwards, to whom he left his eleven-million-pound estate, and another companion named José, a Spanish financier who was, Bacon tells Peppiatt, not just “well endowed, but perhaps too well endowed.” But by that point Bacon is complaining about old age and claiming that he can no longer feel anything for anyone.

So claustrophobic is this round of dinners and drinks—these benders that go on night after night, that move from hotels like Claridge’s to dives like the Colony Room—that we forget time is passing, which makes it a shock when Peppiatt announces that twelve years have passed, their friend Sonia Orwell is dead, and he is having a nervous breakdown over the lack of success in his own life. But then he acquires a magazine, Art International, a wife, and his first child; and when he goes to London and finds himself having a business lunch at the Ritz a few tables away from Bacon and Peter Bogdanovich, it is not only the first time we’ve seen them eating separately, but a strangely poignant moment because of that. The next day, however, Bacon calls to invite Peppiatt on another of the arduous booze slogs that leave Peppiatt wondering how Bacon, much older than he, can do it.

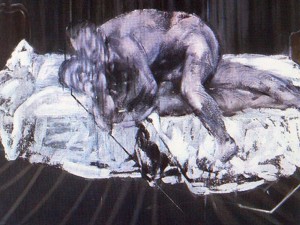

BACON KNEW people hated his work—Punch published a cartoon showing people going into a Bacon show and then coming out, retching—but he was celebrated for it when he was alive, and he became very rich. The art critic John Russell said that British painting could be divided into Before and After Bacon. Why? For one thing, there is a singularity, a unique look to his paintings, whatever one thinks of them. One of Peppiatt’s goals is to find where the art came from; but Bacon, like so many artists, is not about to say. It all happens by chance, he claims, while painting, though the camera has left painters with so few options that he wonders if painting can only come now from a painter’s “critical faculties.” Bacon said he wanted to find the one image that would wipe out all others. Abstract art he found pointless—“nothing comes from nothing”—and he refused to be called an Expressionist. (“I have nothing to express.”) “All painting,” he said, “well, all art, is about sensation. Or at least it should be. After all, life itself is about sensation.”

The sensation Bacon’s painting produces is usually unpleasant. Faces look as if they are covered with nylon stockings, or cut away to expose the tendon and bone beneath; figures are reduced to a tiny space on the canvas, as if they are in a cell being tortured, or shrinking away to nothingness. Much of Bacon’s work looks like the incision a doctor has made and then pulled back with clamps so he can get to the tumor—a glimpse of bone, and muscle, and blood, and tendon. There is a sense of flayed flesh, of nightmares and silent screams. Bacon defended himself by saying every day the newspaper contained horrors that surpassed anything in his art.

Peppiatt compares Bacon to Jekyll and Hyde: after painting these horrific images, he goes out and becomes this bon vivant who “raises the temperature” of every room he enters, this generous host who loves to eat and booze and talk and laugh—until he turns on you, which Peppiatt knows will happen to him eventually, and does, especially when he tells Bacon that he is about to become a father. “And I hope,” Francis repeats, his face going white with fury, “I just hope that if it’s a monster or something, or even if the thing doesn’t have all what’s called its five fingers and all its five toes, you’ll just do it in and get rid of it. Do you see? Do you see what I mean? Just do it in and get rid of it altogether.”

Peppiatt’s memoir does not attempt to explain this outburst. It’s not a biography. It does not go into the moment Bacon’s father threw him out of the house after finding him standing in front of his mother’s mirror admiring himself in her clothes, or his early affairs with older men, one of them a brutal sadist. There are references to his amatory history; but it’s hardly the whole story—though what a story it is! It’s startling to hear that Bacon was once shy. “But I’ve got over that now, and I’ve worked a great deal on myself, because I thought there’s really no point in being both old and shy.” As for advancing years: “Old age is horrible. Horrible.” “It’s like having a terrible disease, and there’s nothing, nothing, you can do about it.” As for his sexuality: “You know, I don’t actually like what are called homosexuals, and I hate it when they go on and on about being queer. I actually prefer men who aren’t queer, or who don’t think they are. In the beginning at least. Afterwards, of course, they’re just as boring as the others.”

All this is a far cry from the diaries David Plante has recently published about his relationship with Stephen Spender—but then the circle around Stephen Spender gathers at small dinners and musical evenings, while the circle around Bacon tends to end in a dive in Paris where the Arab men are so menacing that Peppiatt worries Bacon will be found the next day beaten up in the street. Still, it’s the same era. At one point Sonia Orwell is even heard on the phone inviting someone to a dinner at which Nikos Stangos and “a very talented American writer named David Plante” will be present. There are other curious cameos in this book. Peppiatt even finds himself in a Parisian restaurant with Marlene Dietrich, whose conversation with a couple at a nearby table he strains to hear, though when he does, all she’s saying, it turns out, is: “My husband never let me eat hot dogs.”

And the painter Lucian Freud is, of course, here—he and Bacon were great friends till they had a falling out neither one would explain, so it’s impossible to know if it’s before or after their rupture that Bacon tells Peppiatt that Freud once tried to be homosexual but failed, though “Lucian has what’s called the smallest cock in England and of course you can’t go far in the queer world with that.” There is also a French writer named Michel Leiris, who has an ongoing discussion with Bacon about the difference between realism and reality and who—odd for a writer—arrives at every dinner in a chauffeur-driven Mercedes. But then the pattern of Bacon’s life is very High-Low: in London, the Connaught, in Paris, the Ritz, followed by drinks with butchers at Les Halles and a bar popular with Algerians. Bacon is never at a loss, not even on the day of his great show at the Grand Palais when news reaches him that Dyer has committed suicide in their hotel room—the very room that Bacon reserves for himself on later trips to Paris, to Peppiatt’s astonishment. But then, as Bacon observes elsewhere, “One is never hard enough on oneself.”

Francis Bacon in Your Blood is so enthralling in part because, whatever you think of the art, Bacon is such a welcome corrective to our era of gay marriage, glaad, and service in the military—the age of what a friend calls the White Picket Fence. At the Colony Room, the gay bar from hell, you are in an era of booze and hurt and homophobia, and a cruelty that seems peculiarly English, though part of the viciousness is simply the coldness gay men bring to appearances. “When I want to know what someone looks like,” says Bacon, “I’d never ask a woman. I’d always ask a queer. They’re very accurate. After all, they spend most of their time pulling other people’s appearance to pieces.” Which he proceeds to do himself after a dinner with Michel Leiris: “ I kept looking at the way those veins stuck out on Michel’s temples and wondered what would happen if I pricked them with my fork. I suppose they’d just burst.” But this is too mean even for Peppiatt, who replies, “Well, why don’t you give it a go?” and then departs before they can have a row. To his credit, Peppiatt knows just when to push it and when to drop it, and that’s how he manages to stay friends with this tough old queen (who, like Proust, was asthmatic) for so many years—so many years that when Bacon dies in 1995, and Peppiatt, on a visit to Manhattan, finds the news on the front page of The New York Times, he can only go into the men’s room of his hotel lobby and dry retch. Francis Bacon in Your Blood is a gutsy embrace of a man whose companionship we can experience vicariously only because Peppiatt hung in there long enough to be Boswell to Bacon’s Johnson.

Andrew Holleran’s novels include Dancer from the Dance, Grief, and The Beauty of Men.

Discussion1 Comment

The Gilded Gutter Life of Francis Bacon

Bravo. Excellent review. I suspect it is a better read than the book.

I recently read a research paper authored by a neurologist who theorized that Francis Bacon suffered from a neurological disorder, Dysmorphopsia. The person suffering from this disorder is unable to focus on an object without the object transforming. Of particular interest are Francis Bacon’s portraits. The screaming mouth, the array of teeth are common to people suffering from this disorder. In a broad sense, is a condition in which a person is unable to correctly perceive objects. It is a visual distortion, used to denote a variant of metamorphopsia in which lines appear wavy. These illusions may be restricted to certain visuals areas, or may affect the entire visual field. Francis Bacon talks about this condition in interviews. His ambition in his paintings was to capture this phenomenon.