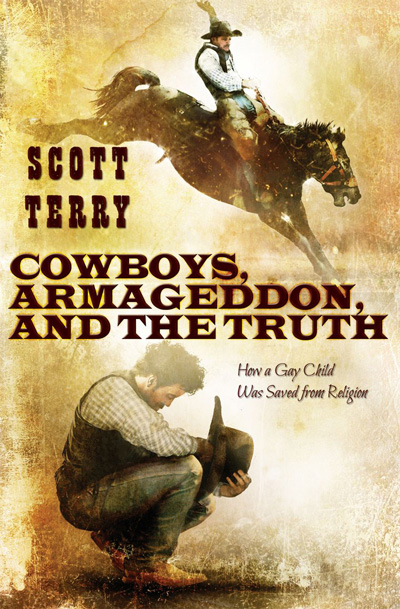

Cowboys, Armageddon, and the Truth: How a Gay Child Was Saved from Religion

Cowboys, Armageddon, and the Truth: How a Gay Child Was Saved from Religion

by Scott Terry

Lethe Press. 289 pages, $18.

SCOTT TERRY’S Cowboys, Armageddon, and the Truth provides ample testimony to the resiliency of the human spirit. Terry’s prose is eloquently direct, and he’s balanced even when describing the appalling abuse that he endured growing up. Terry offers vivid descriptions of his impoverished life in Oklahoma, California, Wyoming, and Utah; his love-hate relationship with the Jehovah’s Witnesses; his coming out as gay; and his experiences as a rodeo cowboy. Psychologists will be fascinated by Terry’s portrait of a seldom discussed human specimen: the sadistic female child abuser.

Scott’s father Virgil and his unnamed mother met in high school in the northern California town of Orland. When she got pregnant, they were “escorted to Reno for a dishonorable wedding on a cold December morning in a miserable caravan of two cars.” Neither was ready for marriage. Virgil “would come home from work each day to sit on the couch and stare at the TV, and that’s when my mother saw where her life was headed and divorced him.”

Virgil took the two kids—Scott and his older sister Sissy—as part of the divorce agreement. At the age of 22, Virgil was a single father and not up to the task. At times the children were cared for by relatives and at times by a succession of baby sitters. Just after Scott’s fourth birthday, these were replaced by a new wife, “Fluffy” (Virgil’s endearment). The two had met at a Jehovah’s Witnesses Kingdom Hall.

Truly a stepmother from hell, Fluffy was an ignorant, large, slatternly woman, with hair of varying shades of red, who wore too much lipstick and covered her furniture in plastic. From the very beginning Fluffy conveyed malice to Scott, who was “bad” (even at the age of four!). Early on Fluffy expressed disdain for children in general, though later, when she had two of her own, she lavished maternal love upon them. Virgil was too weak to protect Scott and Sissy from Fluffy, and both kids would awaken with cuts and bruises from the night before. On one occasion Sissy’s gym instructor saw bruises on her body; police visited the house, but nothing came of it. On another occasion, a Jehovah’s Witnesses elder rebuked Fluffy after learning of her abuse of Scott. Fluffy cried for hours—because her feelings had been hurt.

The dramatic high point of Cowboys comes when the sixteen-year-old Scott finally stands up to Fluffy. When she tries to clobber him, he grabs both of her arms; she tries unsuccessfully to knee him in the balls, and he yells, “Goddamn it! Goddamn it!” Shocked and enraged that her power is broken, she can only scream, “Get out of my house!!!” Scott obeys, and he travels as far as he can with money from selling his bike. Then, with no good alternative, he calls the local police. A handsome and sympathetic young officer, Lt. Dobson, takes charge, turning Scott over to his friends, an elderly couple who serve the boy a dinner of pork and vegetables. When Virgil arrives to pick up Scott, Dobson gets him to agree that Scott needs another home.

When Virgil’s family in California learn of Scott’s predicament, they come to the rescue. He goes to live with Virgil’s older sister, Aunt Dot, a successful real estate broker who lives with her two children in a large ranch house on the top of a cliff, with a swimming pool and horses, surrounded by thousands of acres of open space. For the first time, he receives kindness, understanding, and enough food. Uncle Fred, an old rodeo cowboy, instructs Scott in roping steers, bull riding, and saddle bronco riding. He becomes a high school and later a collegiate rodeo competitor.

The Jehovah’s Witnesses play an important part in Scott’s story. He loved going from door to door with Sissy trying to sell their publications, but experienced adolescent torment from the conflict between his homoerotic desires and the church’s strictures. Finally, after much agonizing and denial, the sight of Sean Connery’s body in the film The Great Train Robbery made him accept that he’s gay. He gradually relinquished the Jehovah’s Witnesses and opted, not for another religion, but for agnosticism.

There is much more to Scott Terry’s well-written and even gripping memoir. Suffice it to say that he eventually found love, success, and happiness. When the circumstances were right, he came into his own.

John Lauritsen’s most recent books are The Man Who Wrote Frankenstein and (as editor) Aeschylus’ plays as translated by Percy Bysshe Shelley and Thomas Medwin.