THE CULTURE OF MALE BEAUTY IN BRITAIN

THE CULTURE OF MALE BEAUTY IN BRITAIN

From the First Photographs to David Beckham

by Paul R. Deslandes

Univ. of Chicago Press. 414 pages, $45.

IN 1982, a photograph of a Brazilian soccer player named Tom Hintnaus appeared on an enormous billboard above Times Square, lying against a whitewashed wall in Calvin Klein underpants with one arm over his eyes, as if dozing on a Greek island—or waiting for someone to come into his room at the baths. Hintnaus was succeeded by Marky Mark, in Calvin Klein briefs, clutching his crotch on the panels lining my bus stop on Second Avenue. Both figures were smooth-skinned and muscular—part of a new, hairless look that was replacing the hairy-chested clone of the 1970s. Queens on Fire Island christened it Hitler Youth. They were not exaggerating. By the end of the ’80s, the Klein campaign had gone full Leni Riefenstahl. In 1989, the model advertising Klein’s undies had his hair slicked back in a 1930s style that made him look exactly like someone in Triumph of the Will.

The arc traced in Paul R. Deslandes’ new book, The Culture of Male Beauty in Britain, ends with something very similar: an enormous photograph of soccer star David Beckham’s six-pack unveiled above the entrance to a Selfridges department store in London in June 2009. Two years later, the male model David Gandy, famous for a Dolce & Gabbana perfume ad in which he floats in a tight white bathing suit near the Blue Grotto of Capri, began a relationship with Marks & Spencer.

The British version of how we got there begins, in Deslandes’ account, back in the 1840s, when a Frenchman named Louis Daguerre invented the daguerreotype. At that time beauty was equated with moral qualities, with admirable character traits. The proportions of classic Greek sculpture still dictated the proper ratio of facial features. Phrenology subdivided the face into sections, like the diagrams guiding butchers in dismembering cows. Good looks were desirable because they would lead to success in business and in life. Almond-shaped eyes were considered the most loving.

When daguerreotypes gave way to photography, men sat for portraits that were reproduced on cartes de visite—small calling cards that were shared at first only with family and friends, but later became collectibles that were put into albums by young women, especially when the subjects were expanded to include celebrities. Books and magazines offered practical tips from barbers and photographers on how to deal with both the bashful sitter and the overly enthusiastic one; instructions not to photograph the bald spot and to be sure to photograph from the side the part is on. The moustache was recommended only for men with bad teeth and weak mouths, and if you had to wear one, it should be thick. A thin moustache was suspicious—as was parting your hair in the middle. “The main thing is to look manly,” proclaimed an article in The Modern Man. “If a man is that he cannot be ugly.”

To be manly you could not be skinny; even sunken cheeks were undesirable. According to Face and Physique or Within and Without (1904), hollow cheeks were said to “disclose a lack of sociability or love of friends.” To avoid the gaunt look, a diet of beef, bread, and beer was recommended. Most important was the skin. According to Alfred T. Story’s The Face As Indicative of Character: Illustrated by Upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Portraits and Cuts (1890): “A good complexion is a paramount condition of beauty, and beauty a sign of loveableness because it indicates normality, and thus purity.”

Here, for instance, is Lord Alfred Douglas sitting calmly beside Oscar Wilde, who’s as plump as a pig, his flesh straining at every fiber of his suit and vest, his leg crossed, his right hand holding a cigarette in the air, looking straight at us with defiant confidence. Beside Oscar sits the agent of his doom, the technically handsome Bosie, whose beauty, if that’s what it was, is ruined by an expression that’s so cold, sullen, and discontented that he looks cadaverous.

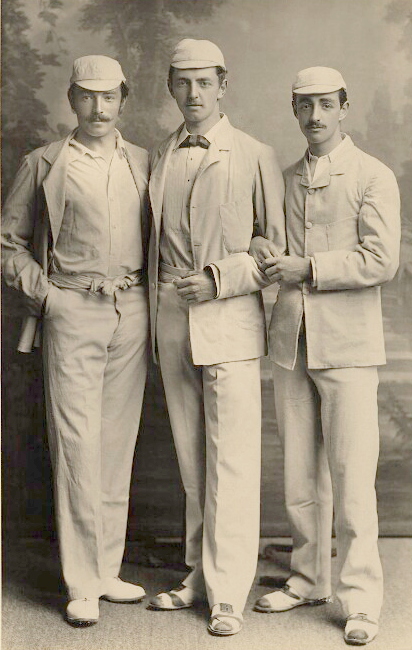

And then there are the Brothers Studd: three cricket players at Cambridge who stand before us in a full-page photograph dressed in “cricket whites,” with fetching caps and thick moustaches. The Victorians may not have read the word “stud” as a double entendre the way the modern reader does, but surely the magnetism in this photograph is sexual. In fact, the image of the Studd brothers may be the perfect example of English manhood at the end of the 19th century—cool, handsome, dandy-athletes, a phenomenon that seems to endure, since every time I see a photo of a soccer player in The Guardian, I wonder: Does one have to look like a model to play professional soccer in Britain? This leads us to the subtitle of Deslandes’ book, “From the Earliest Photographs to David Beckham,” and his six-pack above the entrance of Selfridges in 2011.

The golden age of British masculine beauty—the one people associate with Rupert Brooke and the gilded youth of Oxford and Cambridge—is probably the last part of the 19th century, when A. E. Housman was writing his poems about rural Ganymedes and the artist Henry Scott Tuke was painting adolescent boys bathing naked in secluded coves, their butts often the focus of the painting. Tuke’s work may seem like soft-core porn to us, but critics praised his “frank study of the beauty of male adolescence” for reviving the tradition of the ancient Greeks, who, one journalist wrote, “would justly have been scandalized at the idea that only female beauty of form was to be reproduced in art.” Of course, as Deslandes points out, by this time images of male adolescents were also being used to sell Cadbury chocolates.

Among the admirers of Tuke’s work was the proto-gay activist and writer John Addington Symonds, who wrote him a letter requesting that Tuke send him photos of his “pictures and studies” to help Symonds “cope with the isolation” he was experiencing in Switzerland while recovering from “ill health”—presumably a nervous breakdown brought on by the seemingly irreconcilable conflict between his homosexual desires and his duty as a Victorian man to marry and start a family. (Left out of this book is another example of Symonds’ use of erotic photographs. In a famous story that sums up the tension between ideals of manhood and the homosexual tastes of at least some Britons, one of the young men who gravitated to Henry James near the close of the writer’s life, Edmund Gosse, confessed to Symonds that he got through the funeral service for Robert Browning in Westminster Abbey by peeking periodically at the photograph Symonds had sent him of a naked Sicilian youth taken by Wilhelm von Gloeden.)

At Cambridge—where students actually held a male beauty contest to choose the fairest of them all—the ideal figure belonged to a cricket player named Charles Burgess Fry, an athlete and artist’s model who supplies the only nude photo in this book (lean and muscular was the ideal, not pumped up). Just how elevated the appreciation of male beauty was in this environment is shown by what the poet Rupert Brooke—whose beauty stunned both men and women—wrote to a friend in 1906 about a crush Brooke had on another student, who had, Brooke claimed, “the form of a Greek God, the face of Hyacinthus, the mouth of Antinous, eyes like a sunset, a smile like dawn.”

A photograph of Brooke, who died of a mosquito bite on his way to the Dardanelles during the Great War and came to epitomize all the lost and beautiful young Englishmen of that slaughter, is on the cover of Deslandes’ book, though in this case we see the limitations of photography. His expression is so bland that he looks to me more like the president of a glee club at a large Midwestern university than the poet who wrote “I have filled my days with the splendor of love’s praise.” Another, smaller photo of Brooke in uniform with a cap on is actually more handsome, with his wavy locks hidden. Other paradoxes abound in this book.

The golden age came to an end with World War I, after which the pictures of Cambridge athletes are succeeded by pictures of men in uniform. The most moving is a formal portrait of Lt. Ronald Duncan Wheatcroft. He appears on a page opposite Private John A. Harris. Both men, the captions tell us, died, a few months apart, in 1915. A few pages later we have Lt. C. V. Smith, whose face was so damaged by shrapnel that he serves as an example of the faces that plastic surgeons had to reconstruct (or cover with masks) when soldiers came home with such awful wounds that the nurses trying to feed them could not in some cases find their mouths.

Lt. Wheatcroft is probably more handsome than beautiful, whereas Mr. Gay UK of 2011—who comes later on with his washboard abs, thick head of hair, classic features, a perfect 10—is not even sexy. But then, perfection can often be unerotic, for reasons not gone into here. In his introduction, Deslandes says that “developing a rigid lexicon of beauty is impossible.” The word “beauty,” he writes, “frequently precedes the words ‘culture’ or ‘industry’ to convey the commercial peddling of goods and services. Terms like ‘attractive,’ ‘good-looking,’ and ‘handsome’ tend to be more common in every day parlance … the words ‘beauty’ or ‘beautiful’ being reserved for particular exemplars like Rupert Brooke.” Sometimes attractiveness implies admiration, and sometimes it’s used “to convey qualities that do not rise to the level of the beautiful. … Following the Second World War, discussions of ‘sexiness’ and ‘sex appeal’ became more common, especially from the 1960s on.”

Attempts to define beauty have always bedeviled philosophers. George Santayana defined Beauty as “the promise of pleasure”—a view he later repudiated. Plato said, quoting Diotima in the Symposium, that love is the desire to be born in beauty. But what does that mean—the desire to produce beautiful children? Is beauty simply a matter of the selfish gene—men and women attracted to partners they think they will give them beautiful, healthy children? Then what about same-sexers? What about the timeless beauty in men’s faces and bodies that has something to do with mortality, bravery, and the willingness to sacrifice oneself for a cause—like the volunteers in Ukraine?

We’ve come a long way from the culture that equated male beauty with character traits to one that equates it with sexual desire and uses it to sell consumer products, but we are still struggling with what constitutes the ideal. Beards, thought to be “sissy” in the 1930s by guardians of English masculinity, have come back, or are peaking, or are they on the way out? Even hollow cheeks, once considered a sign of an incapacity for friendship, became desirable on models rebelling against the buffed, beefy body of David Gandy—and now we’re in the era of transgender, androgynous, nonbinary styles. The question is: do the changes of fashion in male beauty have any significance other than as an example of the restlessness of human beings, their desire for change? Cartes de visite have been replaced by Instagram and Grindr, and we all have access to pornography on the Internet, supplied by a seemingly endless number of men who don’t mind being photographed eating ass. We worship beauty and wish we had it. In the epilogue, Deslandes mentions a Danish website called BeautifulPeople.com, which inspired someone else to start one called TheUglyBugBall.com, because, according to its founder, “It struck me that most people aren’t beautiful so there would be a bigger market for ugly people.”

Andrew Holleran is the author of the new novel The Kingdom of Sand(Farrar, Straus and Giroux).