ON JULY 6, 1919, the Institute of Sexual Science opened to the public in a villa in the Tiergarten, Berlin’s central park, a stone’s throw from the Reichstag. The Institute was the first building in the world to house a coherent program of scientific research into human sexual behavior and gender identity, as well as surgical procedures for transgender people. Its director was Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, a gay Jewish Social Democrat and the world’s foremost advocate for what we would call LGBT liberation.

How could a man like Hirschfeld flourish in the city that became the capital of the Third Reich in 1933? And why are his achievements so little known today? To answer the first question, we need to go back to the German-speaking activists who came before Hirschfeld. In 19th-century Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, a large number of treatises were published that detailed the historical trajectory of homosexuality and “nontraditional” sexual practices, particularly fetishes or “paraphilia.” In the 1830s, the Swiss author (and hat designer) Heinrich Hoessli had published Eros: The Male-Male Love of the Greeks, an effort to legitimize homosexual practices by grounding them in Classical Greece.

A few decades later, the German lawyer Karl-Heinrich Ulrichs created a taxonomy of sexual identities, providing a set of terms for academic discussion of these types, notably “Uranian” for male homosexuals. In a paper titled “The Riddle of Man-Manly Love,” Ulrichs contended that same-sex leanings in both men and women were neither “sinful” nor temporary, but innate, immutable, and the result of a mix-up in utero. He identified himself as “Uranian,” a term he derived from the Greek legend of Aphrodite Urania. Heterosexual men he labeled as “Dionian,” butch gays as “Männling,” effeminate queens as “Weibling.” He soon dropped the pseudonym Numa Numantius to write under his own name, and came out publicly before the Congress of German Jurists in Munich—only to be more-or-less laughed out of his profession. He wandered to Italy, where he died in obscurity in 1895.

It was in a letter to Ulrichs that his Austrian colleague Karl-Maria Kertbeny—who claimed himself to be “normally sexed” but whose diaries intimate a string of gay encounters or at least affections—had coined the terms “homosexual” and “heterosexual.” Kertbeny went on to publish a taxonomy of his own, referring to “monosexualists” (masturbators), “pygists” (practitioners of anal sex), and more. These terms were borrowed by the German psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing, coiner of the terms “sadism” and “masochism,” whose tome Psychopathia Sexualis was a forensic study of sexual behaviors practiced by those he believed to be of degenerative heredity. He proposed psychotherapy as a “cure,” but later revised his view and maintained that “contrary sexual feeling” was no illness. As for Freud, he posited an innate bisexuality prior to social conditioning, and adopted a generally enlightened position: “Homosexuality is assuredly no advantage, but it is nothing to be ashamed of. … We consider it to be a variation of the sexual function, produced by a certain arrest of sexual development.”

§

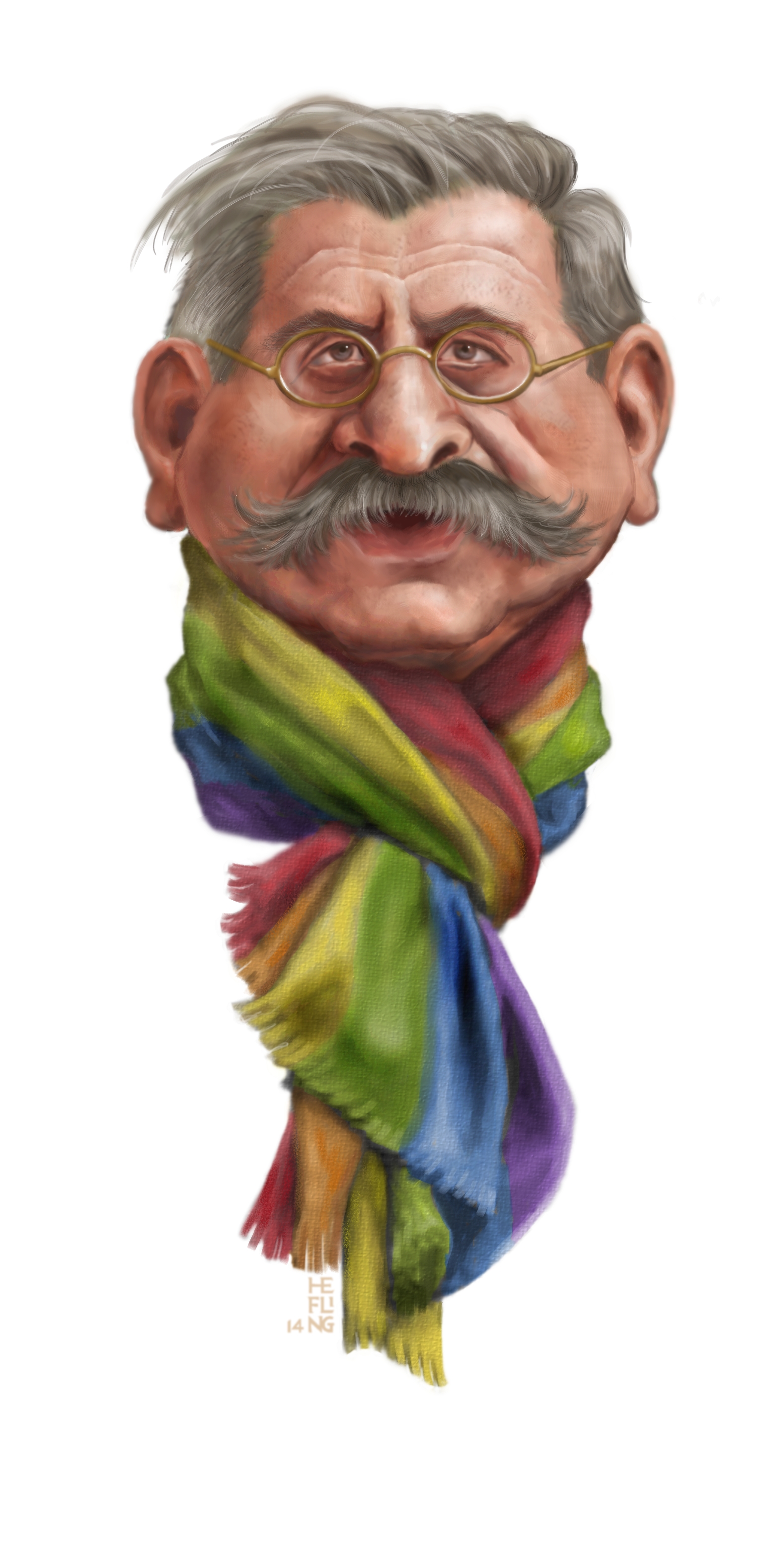

With that as prelude, we can now catch up to Magnus Hirschfeld, who was born in 1868 into a family of Ashkenazi Jews, his father a renowned physician. Hirschfeld studied philosophy and philology before taking up medicine, and would qualify as a doctor in 1892, when Berlin—still constrained by Prussian militarism and parochial traditions but suddenly exploding into a modern metropolis—was the host to a fledgling gay subculture. After medical school, Hirschfeld lived for a time in Chicago, where he found a similar gay enclave in the area now known as “Boystown,” and learned that cities as far-flung as Tokyo, Tangier, and Rio de Janeiro were home to similar neighborhoods.

Back in Germany, Hirschfeld made his way to Berlin and opened a homeopathy clinic in the wealthy Charlottenburg neighborhood. Word soon spread about this 28-year-old doctor who was writing essays about homosexual love under the pseudonym Ramien, and a number of patients booked appointments, largely to find someone with whom to discuss their sexual orientation and the fears it generated (of isolation, arrest, etc.). One of Hirschfeld’s patients, a young army officer too much in despair to be saved, even dedicated his suicide note to the doctor, with the parting words: “The thought that you could contribute to a future when the German fatherland will think of us in more just terms sweetens the hour of my death.”

By the time he published this tome, Hirschfeld had already cofounded the world’s first organization to promote LGBT rights—the civil activist group calling itself the Scientific Humanitarian Committee. The Committee, which grew to around 500 members and had branches in Germany, Austria and the Netherlands, was primarily dedicated to campaigning for the repeal of Section 175, under which male homosexual behavior could be prosecuted. To that end, the group wished to demonstrate the normality, prevalence, innateness, and global nature of the homosexual orientation, and gathered the signatures of prominent figures, mostly straight allies like Albert Einstein. Committee member Kurt Hiller’s paper, “Section 175: The Disgrace of the Century,” was delivered to the German government—but to no avail.

Hirschfeld himself was called to testify at a highly controversial trial lasting from 1907 to 1909, during which a number of men in the inner circle of Kaiser Wilhelm II were accused of homosexual conduct. These proceedings were electrified when journalist Maximilian Harden exposed the relationship between Prince Philipp of Eulenburg and Hertefeld, and General Kuno von Moltke—two of the Kaiser’s closest friends—and suggested that Philipp’s palace was operating as a gay salon. Prince Philipp and Moltke both attempted to sue Harden for libel. Hirschfeld testified that he believed Moltke to be homosexual—but said there was nothing wrong with that. The right-wingers of the day were outraged by what they saw as an attempt to besmirch the honor of the German military. Hirschfeld’s clinic was vandalized with graffiti—a harbinger of things to come: “Dr. Hirschfeld a Public Danger: the Jews are Our Misfortune!” In the end, the trial had quite the opposite effect to what Hirschfeld had sought. Rather than raising awareness of the plight of gay men and ameliorating their situation, it ushered in a crackdown on homosexual behavior and a rise in court cases and convictions. At the same time, the Kaiser instigated a cover-up of queerness in the German army—during which time, at one of his hunting-lodge parties, the chief of the Military Secretariat, Dietrich von Huelsen-Haesaler, died of a heart attack while performing a dance in a tutu.

§

The Scientific Humanitarian Committee produced numerous publications from 1899 to 1923, including its annual “Yearbook of Intermediate Sexual Types,” a series of case studies on homosexual, intersex, and transgender individuals. Since a nonbinary presentation was scarcely possible at this time—one had to appear male or female—many subjects spoke of vacillating between male and female presentation, and would be photographed in a dress, a suit, and indeed naked. This was the world’s first scientific journal to deal with variant sexual behavior, with contributors such as Richard von Krafft-Ebing. Other journals and magazines followed. In 1896, Adolf Brand began to publish the magazine Der Eigene (“The Special Few”), the world’s first gay magazine. With a print run of around 1,500, Der Eigene appealed to a readership interested in what might be called hypermasculinity, focusing on physical fitness and virility. For lesbians, the leading magazines were Die Freundin (“The Girlfriend”) and Frauenliebe (“Love of Women”). Hirschfeld wrote the preface to Berlin’s Lesbian Women by the journalist Ruth Roellig, an overview of lesbian gathering places in the capital, which was freely available in the city’s kiosks and train stations.

Hirschfeld had already published his own report on queer nightlife and cruising, “Berlin’s Third Sex,” in which he describes a dozen major gay bars in the capital, sex work of all permutations, and the city’s drag scene. He elaborated on the old idea of homosexuals as a “third sex” by making a clear distinction between sexual orientation and gender identity, and he became engrossed in research on the latter. In 1910, he coined the term “transvestite,” and he later identified two types of transvestism, one intended to bring about sexual arousal, what is now called transvestic fetishism, the other an expression of an innate, permanent identity—what we would call transgenderism.

From 1908 onward, patients of Hirschfeld were able to apply for special “transvestite certificates,” diagnostic notes that the holder could take to the police to obtain a stamped document guaranteeing their right to wear masculine or feminine clothing in public. One of those to obtain such a license was the Berliner trans man Berthold Buttgereit, born in 1891, who was identified as female at birth but who felt himself to be male from an early age. He visited Hirschfeld at the age of twenty and was diagnosed as a “total transvestite,” meaning that he was fully identified as male. He was able to obtain a transvestite certificate in 1912 and even a corresponding passport in 1918. When a new ruling in April 1920 made it possible for “transvestites” to legally change their names (though not the gender marker on their documentation), he did exactly that, publishing a classified ad in his local newspaper to announce his new moniker. Buttgereit stayed in Germany, survived the Nazi era, and died at the age of 92.

From 1908 onward, patients of Hirschfeld were able to apply for special “transvestite certificates,” diagnostic notes that the holder could take to the police to obtain a stamped document guaranteeing their right to wear masculine or feminine clothing in public. One of those to obtain such a license was the Berliner trans man Berthold Buttgereit, born in 1891, who was identified as female at birth but who felt himself to be male from an early age. He visited Hirschfeld at the age of twenty and was diagnosed as a “total transvestite,” meaning that he was fully identified as male. He was able to obtain a transvestite certificate in 1912 and even a corresponding passport in 1918. When a new ruling in April 1920 made it possible for “transvestites” to legally change their names (though not the gender marker on their documentation), he did exactly that, publishing a classified ad in his local newspaper to announce his new moniker. Buttgereit stayed in Germany, survived the Nazi era, and died at the age of 92.

The name-change legislation of 1920 is emblematic of how much progress was made by and for queer Germans during the Weimar Republic, the period of 1918 to 1933. In the first years of this era, Hirschfeld’s work took on new momentum. Berlin’s leftist government initially forbade prosecution under Section 175. Hirschfeld purchased his villa near the House of Parliament to house his Institute of Sexual Science. From here, he and his staff sent out thousands of surveys to glean information about people’s sexual experiences and proclivities. Passersby—many of them heterosexual, concerned about marital harmony, contraception, and venereal disease—could also deposit anonymous letters in the postbox on the clinic’s fence, which would be answered in a public plenum each Monday evening. In addition, Hirschfeld offered counseling services geared to what he called “Adaptation Therapy,” not to be confused with “conversion therapy.” Hirschfeld’s goal was to “reassure the homosexual personality, whether male or female; we explain that they have an innocent, inborn orientation, which is not a misfortune in and of itself but rather experienced as such because of unjust condemnation.”

Hirschfeld also opened a new Museum of Sex, an educational resource open to the public. On display were a bicycle-powered masturbation machine and an international collection of dildos. On the clinical staff were psychiatrists, a gynecologist, an endocrinologist, and a dermatologist, all paving the way for the development of the first medical treatment of transgenderism. The Institute became Europe’s ultimate gathering place for sexual minorities, and particularly for trans people, many of whom moved in for a brief or longer spell, sometimes joining the staff to pay their way. Hirschfeld, too, moved into his own quarters, which he shared with his life partner Karl Giese. Passing through were the philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin, dancer Anita Berber, communist publisher and Reichstag deputy Willi Muenzenberg, French writer André Gide, Russian film director Sergei Eisenstein, and English archeologist Francis Turville-Petre with his friends Christopher Isherwood and W. H. Auden.

Some of the earliest transgender people to undergo gender reassignment surgery—hormone therapy was not yet possible—also stayed at the Institute for a time. Dora or “Doerchen” Richter, who had been a patient at the Institute and remained living there as a domestic servant, was the first known trans woman to undergo a complete surgical transition. She had been brought up on a farm in conditions of abject poverty, had always identified as a girl, and had been imprisoned for cross-dressing before finding a home at the Institute. She completed her surgical transition in 1931. Lili Elbe, whose story was the basis for the movie The Danish Girl, was also treated in Germany, having her first surgery at the Institute with Dr. Erwin Gohrbrandt under Hirschfeld’s supervision, and going on for further treatment at the Dresden Municipal Women’s Clinic. Regarding Dresden as the place of her rebirth, she changed her surname to “Elbe” in honor of the river that runs through the city—but died at 48 of complications following her final surgery.

Another patient, or client, at the Institute was the trans (probably intersex) German-Israeli author and social reformer Karl M. Baer (1885–1956). Having been raised as a girl, Baer was in his twenties when he met with Hirschfeld. In 1906, he became the first person to undergo sex reassignment surgery. The next year, he obtained a new birth certificate listing him as male. He was a social worker and advocate for women’s right to vote and to receive higher education, and he campaigned to end female trafficking. In 1938, he and his wife emigrated to Palestine, where he worked as an accountant, and he is buried in Tel Aviv under the name Karl Meir Baer. He had written a semi-fictional autobiography under the name “N. O. Body,” with the title Aus eines Mannes Maedchenjahren (“Memoirs of a Man’s Maiden Years”). This was adapted into the film Wer ist Nobody? (‘Who is Nobody?’), of which no copy seems to have survived the Nazi era.

The Institute also funded the production of the 1919 silent movie Different from the Others, which has been digitized and screened at various festivals in the last decade. Hirschfeld co-wrote the screenplay with director Richard Oswald. The protagonist, Paul Koerner, was played by actor Conrad Veidt of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari fame. After trying “conversion therapy” through hypnosis, Koerner visits Hirschfeld at the Institute and describes his travails, only to be reassured that his orientation is perfectly natural and that he can live a fruitful life. But this is not to be. Though there are some moments of joy in the footage of drag queens, gay men, and lesbians partying, the film presents a grim vision of homosexual life, blighted by manipulation, blackmail, and suicide. Hirschfeld’s intent was to demonstrate the plight of gay men due to Section 175 and to societal disapprobation. Indeed, the movie itself would soon be banned from public screening and could only be viewed at the Institute.

§

As the Weimar Era fell increasingly under the spell of National Socialism, Hirschfeld and his friends were ever more at risk. He was set upon by right-wing thugs after giving a lecture in Munich in October 1920 and beaten so savagely that the newspapers reported his death. Since he was winning fame abroad, he embarked upon a grand tour, arriving in New York in November 1930—not knowing then that he would never return to Germany. His American expedition was assisted by Dr. Harry Benjamin, a fellow German sexuality scientist and endocrinologist who would treat many trans patients in the U.S., particularly after the advent of synthetic hormones. Hirschfeld spent six weeks in New York, socializing with fellow luminaries such as Langston Hughes—and going to the bathhouses. It was on this tour that he was given the nickname “the Einstein of Sex,” though he soon realized that his audiences were less prepared to hear about sexual intercourse and homosexuality than their German counterparts. He traveled all the way to California, his speech in the Dill Pickle Club in Chicago causing a scandal along the way. In what is sometimes called his “straight turn,” he geared his American lectures more toward the cultivation of romantic intimacy among heterosexual couples.

Hirschfeld resolved to continue touring and went on to Japan and later to Shanghai, where he met Li Shui Tong, who became a second partner along with Karl Giese. (Tong and Giese became friends, but it’s not clear whether they were lovers.) Hirschfeld and Tong traveled on through Indonesia, India, Egypt, and Palestine before arriving in Greece and then moving to France. It was in a Paris cinema that Hirschfeld watched the newsreel footage of his archive—20,000 books, 35,000 photographic slides, and magazines, and thousands of files—being publicly burned in the center of Berlin on May 10, 1933, which marked Hitler’s 100th day in office. Ludwig Levy-Lenz, the gynecologist at the Sexual Science Institute, another exile in Paris, later claimed that the Institute’s archive was targeted so early on because of the “intimate secrets” of Nazi Party members that may have been archived there.

In 1935, on the day he turned 67, Hirschfeld died in his apartment in Nice. Giese’s French visa was revoked after he was arrested for “public indecency” at a Paris bathhouse, and he moved to what was then Czechoslovakia, dying by suicide in 1938. Tong, whom Hirschfeld called his “faithful disciple,” had hoped to continue Hirschfeld’s legacy but was aggrieved and restless. He studied medicine, then economics, in Zurich before enrolling for a time at Harvard and then returning to Switzerland, never completing a degree. During the homophobic decades of the Cold War, he distanced himself from his past. He was contacted by the Berlin regional court about Hirschfeld’s property and inheritance in 1958, but he wanted nothing to do with the issue and vanished into solitude from then on.

Tong died in his apartment in Vancouver in 1993, and his possessions ended up boxed up outside his home, where a fellow tenant discovered his last papers as well as the files and diaries of a man named Magnus Hirschfeld. A decade later, these items ended up in the possession of Ralf Dose, director of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society in Berlin. Aided by the resurgence of interest in LGBT history in recent decades, this discovery has led to a new appreciation of Hirschfeld as a courageous and innovative scholar who was way ahead—too far ahead, perhaps—of his times.

Finn Ballard, founder and operator of Finn Ballard Tours, offers a wide range of historical and cultural tours of Berlin.

Discussion1 Comment

I’ve been emerging myself in this period to create a series of artworks. Your article is a great find in my journey. of the past.