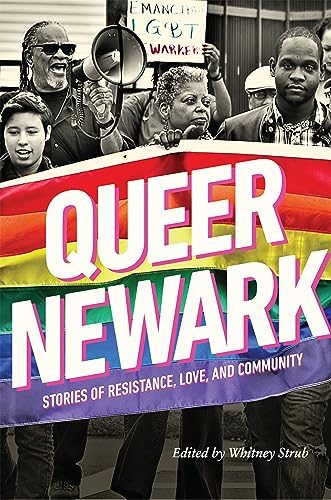

QUEER NEWARK

Stories of Resistance, Love, and Community

Edited by Whitney Strub

Rutgers Univ. Press. 320 pages, $27.95

IF SOMEONE had asked me a month ago what I knew about the history of queer Newark beyond the fact that a queer Black teenager named Sakia Gunn was murdered there in 2003, I would have had to reply, “Not much.” But thanks to Queer Newark: Stories of Resistance, Love, and Community, that has now changed considerably. Edited by Whitney Strub, the book brings together a number of essays by academics, public intellectuals, and community activists. By the time I had finished reading them, a rich and varied history had come alive.

Arranged roughly chronologically, the stories they tell suggest a history of LGBT Newark that separates into three periods. The first period stretched from the post-Prohibition era of the 1930s to the late 1960s. During these decades, when Newark was an industrial city with a largely white population, a bar culture emerged that provided many venues for socializing by the late 1950s. Harassment by the police and, especially, by the state’s Division of Alcoholic Beverage Control (ABC) led to arrests and bar closings over the years, but in 1967 a court case brought against the ABC by several bars—including Murphy’s, a deeply beloved gathering spot—guaranteed the right of “homosexuals” to meet in bars and be served.

This historic decision occurred in the same year that African-American people in Newark rose in rebellion. The days of burning buildings, police actions, and community revolt brought Newark bad press nationally, accelerated white flight to the suburbs, and solidified a Black majority population. Over the next decades, from the 1970s into the ’90s, what emerged was a vibrant club and ballroom scene. Music, dance, and performance brought Black queer Newark together, and the ballroom scene helped create safe spaces for younger queers and trans individuals who were not accepted by their families.

This second period coincides with the onset of AIDS in the 1980s and ’90s. Compared to much of urban America, AIDS in Newark disproportionately affected straight male drug users and their female partners. However, a significant number of gay men and MSMs (men who had sex with men) were also affected. However, the press and television media almost completely ignored this fact. The city’s mayor in the 90s, Sharpe James, flagrantly denied that Newark had any gay residents. And so it was left to community activists to spread knowledge and offer services to those affected. The essay on AIDS describes Project Fire, which reached out through the club and ballroom scene and developed educational programs like “Hot, Healthy, and Horny” to push men toward safer sex while affirming sexual passion and desire. But while Project Fire did important work, the combination of AIDS and continuing economic decline led to a shrinking of the club and ballroom scene by the end of the century. And beyond the AIDS prevention work, Newark in this period did not have much of an organized activist movement.

Then, in 2003, a young butch lesbian teenager, Sakia Gunn, was murdered by two men who were sexually harassing her on the street. Unlike the violent murder of Matthew Shepard, a white teenager in Wyoming, Gunn’s killing received almost no media attention, and neither the police nor the city government did much to address the crime and the issues it raised. However, as the last few essays in the collection dramatically recount, LGBT residents of Newark rose up in response. Black women were pivotal in building and sustaining this wave of activism. The Newark Pride Alliance formed in the wake of Gunn’s death. The city had its first Pride week in 2005. Mayor Corey Booker created a Mayor’s Advisory Committee on LGBT issues in 2009. A community center was established in 2013. Activists formed Project WOW, a program designed to serve queer youth.

Also of note, during the Obama presidency, the Department of Justice began an investigation of the Newark Police Department. In addition to establishing an independent monitor to keep track of police behavior, the DOJ urged the department to “engage with the LGBT community … and develop training on policing related to sexual orientation and gender identity.” While this did not solve the entrenched problem of police harassment or eliminate the community’s deep distrust of the police, it was a dramatic step forward, an indication of how community activism—notably that of African-American women in this case—could make a difference.

The accounts in Queer Newark were made possible in large part by the creation of the Queer Newark Oral History Project in 2011. Scores of interviews have been collected, some recounting events going back to the World War II era and the 1950s. They make the essays come alive with deeply personal accounts of individual lives across three-quarters of a century. Besides the many quotations contained in each essay, Strub also included more extended excerpts between the chapters. By the time I’d finished reading Queer Newark, I felt that I had not only absorbed some fascinating history but also had formed relationships with many of its key characters.

John D’Emilio, professor emeritus at the U. of Illinois–Chicago, is the author of Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin.