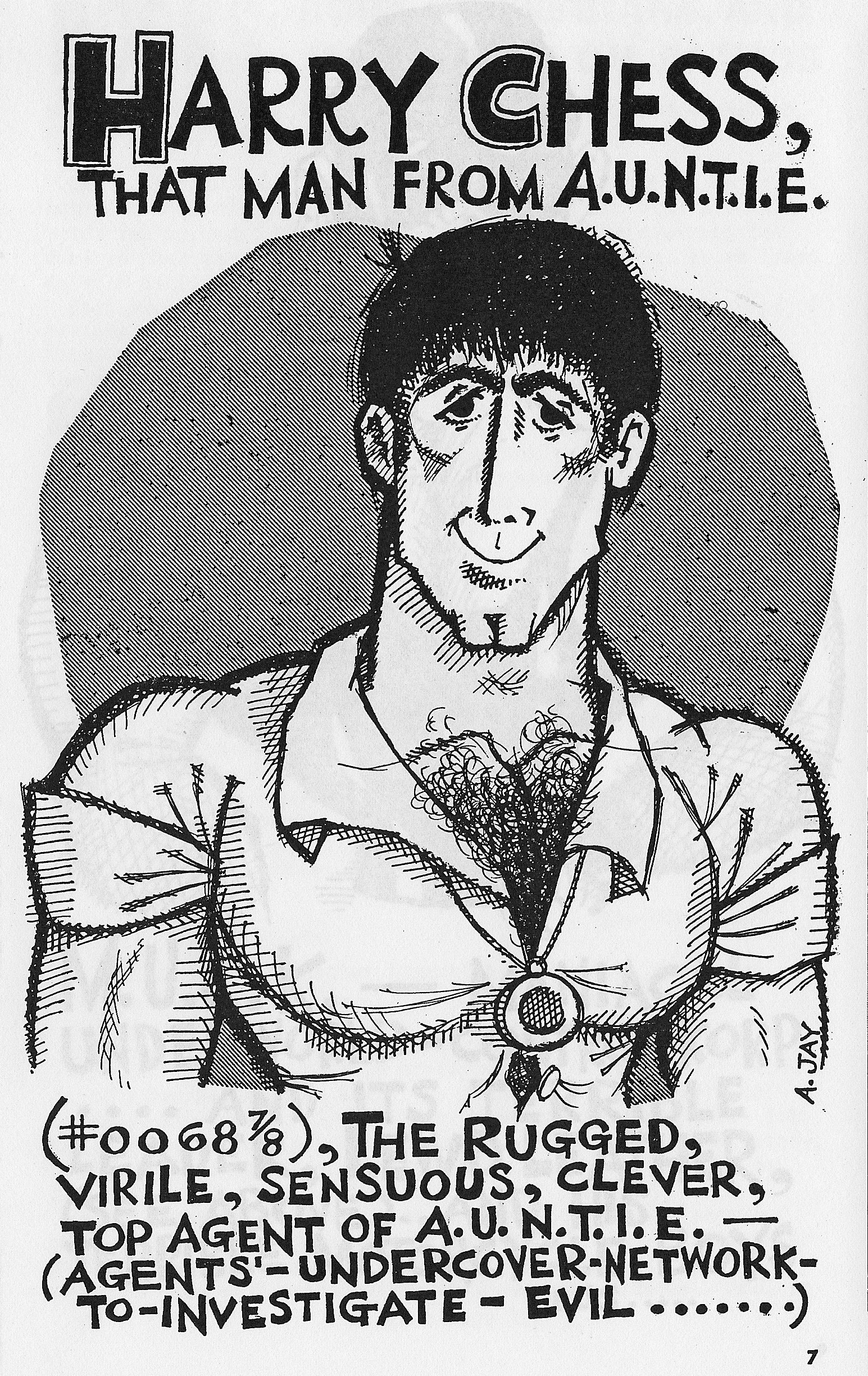

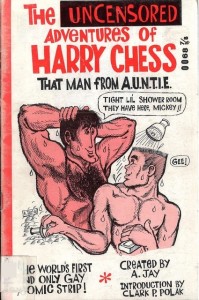

THE WORLD’S FIRST gay comic strip was arguably Harry Chess: That Man from A.U.N.T.I.E., which first appeared in the Philadelphia homophile publication Drum from 1965 to ’66. The strip pits the hirsute pectorals of protagonist Harry Chess, secret agent #0068 7/8 of the Agents’ Undercover Network to Investigate Evil (A.U.N.T.I.E.), and his muscular but monosyllabic teenage “assistant” Mickey Muscle, against a series of colorfully evil and sexually naughty nemeses. Although its title was inspired by the 1964-68 television series The Man from U.N.C.L.E., the strip was a campy and (homo)sexually explicit spoof of the larger international espionage genre with its futuristic gadgets, shadowy acronymic organizations, and morally ambiguous secret agents whose exploits were regularly punctuated by gratuitous sexual encounters. But more than just another example of the mock-Bond phenomenon, Harry Chess demonstrates the important role of popular visual culture in the mid-1960s emergence of a gay liberationist sensibility in the U.S.

Recalling that in mid-century gay slang “auntie” was a pejorative term for an older, effeminate gay man, we can understand that the virile, handsome, and above all masculine Harry Chess really was “that man from A.U.N.T.I.E.”—a departure from older, seemingly outmoded modes of gay sensibility. Polak was perhaps at the more radical edge of a general shift, evident in other mid-1960s homophile organizations, toward a positive revaluation of homosexuality and a rejection of scientific and medical expertise on “the homosexual” in favor of the personal authority and everyday experience of actual gays and lesbians. Key to realizing Polak’s vision was the Janus Society’s monthly newsletter, which he renamed Drum: Sex in Perspective. Featuring national and international news coverage, editorials, cultural reviews, advice columns, parodies, and, of course, a comic strip, Drum was the prototype of later gay lifestyle publications such as Genre and Out. With Drum, Polak sought “to put the ‘sex’ back into ‘homosexual,’” a goal reflected in the how-to column “A Beginner’s Guide to Cruising” and the use of male physique photography on the cover. An ad in the New York Mattachine Society newsletter (November 1964) succinctly characterized Drum’s approach: “Drum stands for a realistic approach to sexuality in general and homosexuality in particular. Drum stands for sex in perspective, sex with insight and, above all, sex with a sense of humor. Drum represents news for ‘queers,’ and fiction for ‘perverts.’ Photo essays for ‘fairies,’ and laughs for ‘faggots.’” Drum’s combination of news, sex, and humor proved immensely successful. Circulation topped 10,000 after two years, with a print run two or three times that of other homophile publications. The Birth of Harry In 1964, Polak placed classified ads in East Coast newspapers seeking “a cartoonist for a new gay and sophisticated magazine.” (A subsequent form letter responding to applicants suggests that a great many cartoonists misunderstood Polak’s use of the word “gay,” a fact that probably explains why newspapers accepted the ad in the first place.) Allen J. Shapiro, a Pratt Institute of Art-trained illustrator, responded to an ad in The New York Times with an 11” x 14” drawing of Harry Chess wearing bikini underwear, signed with the pen name “A. Jay.” Polak later remembered thinking: “That was it.” The Harry Chess character first appeared in Drum’s November 1964 issue as a graphic accompaniment to the parody “Franky Hill: Memoirs of a Boy of Pleasure,” and the stand-alone comic strip debuted in the April 1965 issue. The strip was a collaborative product, with Shapiro first roughing out the story, then meeting with Polak to fine-tune the humorous dialogue. Harry Chess: That Man from A.U.N.T.I.E. borrowed the popular Bond film formula, but re-imagined it from a mid-1960s gay male perspective, for a gay male audience, to affirm a diversity of gay male sexual styles. The strip’s megalomaniacal villains and their nefarious plots reflected actual threats to a vulnerable gay male community, while the agents of A.U.N.T.I.E. embodied a sex affirming, muscular, and always humorous resistance to their would-be oppressors. Every detail of the strip—the names of spy organizations, the agents, the plots and locales—was saturated with sexual innuendo and gay double entendres. Polak and Shapiro took special delight in winking at the well-known homoerotic valences of hetero-masculine rituals, such as men’s wrestling, physique photography, military academies, Hollywood westerns, and bodybuilding contests. Described as a “stripped comic,” everyone in Harry’s world seemed to have an aversion to clothing, which conveniently facilitated his many humorous sex-capades. Like James Bond, Harry’s adventures always involved plenty of sex, and the sex was always plenty adventurous. The strip’s theme was established in the very first storyline when the “very mean and terribly oversexed” Lewd Leather and his motorcycle gang from the Maniacal Underworld Control Korp (M.U.C.K.) “trick-nap” the hunky but virginal Biff Ripples, who has just been crowned “The World’s Most Succulently Beautiful Male” at the Mr. Planetarium Physique Contest, taking place in the Grand Ballroom of the Slumhouse YMCA. After Lewd cuts the power, the all-male audience devolves into a riot—or is it an orgy?—in the resulting darkness. Agent FU2, head of the secret A.U.N.T.I.E. organization, alerts “top agent” Harry Chess, who’s busy “working out” Mickey Muscle at his New York brownstone. The pair heads for the Bloody Basket, a seedy gay bar, to consult with stubbly-chinned informant, bouncer, and “Girl Bartender” Big Bennie. They learn that Biff’s abduction was ordered by the wealthy, monocle-wearing æsthete Gaylord Dragoff, who wants to add Biff to his private “piece corps.” Big Bennie directs Harry and Mickey to a gay bathhouse, where they find Lewd and his boys have absconded with Dragoff’s $5,000,000 reward—but not before having their way with a not too unwilling Biff Ripples, left hogtied and moaning contentedly in the steam room. Dragoff consoles himself with the fact that Biff is alive and a natural for “The Steve Reeves Story,” a future film currently casting in Hollywood. In subsequent “undercover operations,” Harry and Mickey encounter villains such as the Scarlet Scumbag, the Groping Hand, Brownfinger and his sidekick Belowjob, and Mung the Mean and his Deadly Dildo Death Squad. They foil a plot by the Pornography Intern Solely for Soviet Hotrocks (or P.I.S.S.H.) to corner the world’s gay porn market. Next they recover the FBI’s official “homo-file” and the kidnapped astronaut Hunky Dorie. Another time they successfully prevent ground glass from being dumped into the vats of the “Cay-Why” factory. Following the Bond formula, Harry and Mickey are subjected to wildly inventive and heavily sexualized tortures and enjoy plot-incidental sex with a variety of gorgeous guys, with names like Tooshie Supreme and Gary R. Pigeon. Harry Pro and Con: Signs of the Times The strip’s explicit sexual references and raunchy humor were a magnet for criticism, reflecting larger factional divisions inside the era’s homophile organizations and the wider gay community. Clearly favoring a politics of conformity and respectability of the kind that Polak detested, Richard Inman, then president of the nascent Mattachine Society of Florida, wrote to Janus Society member Barbara Horowitz in April 1965: “Look at your champ Harry Chess. Frankly I think the whole idea is SICK. … What is the sense of trying to see how MUCH you can get away with? What is the sense of such unnecessary defiance? … Does it reflect what the homophile movement stands for? … Hell no it doesn’t and the only result could be one of damage to the movement.” At the time, printed matter that depicted or discussed homosexuality was a favorite target of censorship campaigns by crusading politicians using anti-obscenity laws. Physique magazines and homophile publications were regularly seized by local police, the FBI, and the Postmaster General’s office. Polak and Shapiro anticipated the threat of censorship when writing Harry Chess. As Polak put it, “our greatest single problem is attempting to predict which of our quips we can use without ending in jail on an obscenity rap.” Understandably, full-frontal nudity was not depicted in Harry Chess while the strip appeared in Drum, even after the 1962 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in MANual Enterprises v. Day, which held that physique magazines with nude models were not inherently obscene. Despite these precautions, Harry Chess appears to have sharply polarized Drum readers. A letter from Toronto i These extreme positions were made vividly clear in letters printed in the December 1965 issue. A Canadian subscriber described by the editor as a “leather and boot fetishist” wrote: “Above all else, I enjoyed the right hand, top panel of Harry Chess (Drum, Oct.) marked ‘odors’ in the control panel of the torture chamber. I was really thrilled to read amongst the scents of torture the words ‘leather’ and ‘extract of cycle boots.’” This was immediately followed by this opinion from San Francisco: “What began as a funny romp has ebbed into a sick excursion into the depths of what I feel is [the]worst depravity. I can only suggest, for whatever its [sic]worth, that you drop Harry Chess.” Polak took delight in tweaking what he saw as his critics’ prudish and outmoded sensibilities by frequently citing their objections to Harry Chess. Characterizing his critics as “failing in a sense of humor,” Polak preened: “[T]here is a substantial number of persons who are as opposed to Harry as the pre-t.v. Batman was opposed to girls. They call him obscene, crude, vulgar and about the only thing I can think of answering them is that I agree, and I am glad to see they understand him so well.” Although the strip’s themes implied that Harry Chess and Mickey Muscle represented a larger gay constituency, certain clues suggest the characters were more than abstract idealizations. In a 1966 Harry Chess compilation, Clark Polak concluded his description of Shapiro’s contributions to the strip with the revealing assertion that “Harry Chess is A. Jay.” Indeed, later self-representations by the cartoonist confirm his physical similarity to the muscular, hairy-chested secret agent he limned for Drum. Armed with this clue, it becomes easy to see the resemblance to A.U.N.T.I.E. chief FU2 in photographs of the young Clark Polak. But lest we judge Harry Chess to be nothing more than the public expression of Polak’s and Shapiro’s egotistical fantasy life—though it was that—we should also note the ways in which the strip invited readers to imagine themselves into Harry’s world. Anticipating (but also parodically mimicking) the censor’s black-marker “redactions” in a way designed to enlist the reader’s X-rated imagination, Shapiro coyly included blacked-out panels illuminated only by thought balloons filled with ambiguous but suggestive dialogue, as in this “shower scene”: “Dropped what soap?” “Ooooooow!” “I’ll give you 40 minutes to stop that!” “Glorie-oskie!!” “What’s this damp, sweeling [sic]thing I feel?” “A sponge silly!” “Gee!” Through such visual and narrative strategies, Polak and Shapiro welcomed readers into a fantastic if recognizable world structured by gay male sexual desire, the articulation of which constituted a form of both self-expression and resistance. Harry Chess: That Man from A.U.N.T.I.E. represented a new kind of sexual politics in which a self-affirming, sex-positive, and subversively humorous homosexuality triumphed over the considerable real-world forces arrayed against it. It helped to catalyze a gay liberationist sensibility by offering a cultural space in which gay men could envision themselves as both heroic and homosexual, while the agents of homophobic oppression (often closeted homosexuals) are portrayed as sexual deviants and villains. After Drum: Go West, Hung Man! From its modest and somewhat amateurish beginnings in Drum, Harry Chess would subsequently “star” in a number of thematically related comic strips published in several gay publications well into the 1980s. Beginning in 1965 the strip was translated into German and Swedish, making Harry an international icon of gay male culture. But, for reasons that remain unclear, in 1966 Drum ceased publishing the strip. But Harry’s career as a secret agent wasn’t over. He resurfaced in a different strip in Drum in 1967, which continued until the newsletter ceased publication in 1969. That same year, Shapiro launched The Super Adventures of Harry Chess in the New York-based Queen’s Quarterly. In 1977, Harry jumped ship to Drummer, a periodical whose hyper-masculine leather orientation was ideally suited to the strip’s espionage theme and its protagonist’s physical features and sexual proclivities. (Shapiro was the founding art director of the San Francisco Drummer and produced illustrations associated with that city’s bathhouses and leather community until his death of AIDS in 1987.) In the 1980s, select episodes of the original Harry Chess strip were republished in anthologies of gay male comics, but without reference to their earlier origins. In the later series, all references to A.U.N.T.I.E. had vanished, and Harry was described as “secret-super agent #2 for F.U.G.G. (Fist-flying Undercover Good Gays), the super secret protective force of the Mottomachine Society (and we all know who they are!)” Over these years the crudeness and hesitancy of Shapiro’s early drawing style developed into a confident visual artistry in the service of more elaborate and explicit narratives. Where Harry Chess: That Man from A.U.N.T.I.E. tiptoed around full-frontal nudity, the later strips positively wallow in the sexually fantastic and esoteric. Eventually, even Harry went “the full Monty,” rendered by Shapiro in to-be-expected anatomical hyperbole. The cultural politics of the strip had shifted from critiquing the mid-century tactics of respectability and asserting a sex-positive militancy to exploring the sexual possibilities that these earlier efforts had opened up. The author would like to acknowledge Marc Stein (York University), the GLBT Historical Society of Northern California, and the San Francisco Public Library for their help with this research. Michael J. Murphy is assistant professor of Women and Gender Studies at the University of Illinois, Springfield. Harry Chess resulted from a fundamental shift in priorities and tactics within the Philadelphia-based Janus Society, one of a number of homophile organizations on the Eastern seaboard. In 1963 Janus elected as its president Clark P. Polak, a candidate who was openly critical of the organization’s past leadership, and promised a more structured, business-like organization with a strong community presence. But beyond organizational reform, Polak rejected the Janus Society’s strategies, which tended toward accommodation and assimilation, in favor of a gay-centered and sex-affirmative politics. In a 1966 Drum editorial, he described earlier homophile activists as “a group of Aunt Marys who have exchanged whatever vigorous defense of homosexual rights there may be for a hyper-conformist we-must-impress-the-straights-that-we-are-as-butch-as-they-are stance. It is a sell-out.”

Harry Chess resulted from a fundamental shift in priorities and tactics within the Philadelphia-based Janus Society, one of a number of homophile organizations on the Eastern seaboard. In 1963 Janus elected as its president Clark P. Polak, a candidate who was openly critical of the organization’s past leadership, and promised a more structured, business-like organization with a strong community presence. But beyond organizational reform, Polak rejected the Janus Society’s strategies, which tended toward accommodation and assimilation, in favor of a gay-centered and sex-affirmative politics. In a 1966 Drum editorial, he described earlier homophile activists as “a group of Aunt Marys who have exchanged whatever vigorous defense of homosexual rights there may be for a hyper-conformist we-must-impress-the-straights-that-we-are-as-butch-as-they-are stance. It is a sell-out.”

n the September 1965 issue begged that Harry not be dropped, while a reader from Santa Monica cautioned: “Harry Chess is your Henry Miller. Squeamish souls had better look elsewhere. Of course you may be banned eventually (by jealous witches).” In the November 1965 issue editor Polak reported, in answer to a reader’s query about the popularity of the previous issue, that “the most violent reactions came about Harry Chess. About 80% made cancellation threats if we dropped him and the other 20% threatened to cancel if we did not drop him.”

n the September 1965 issue begged that Harry not be dropped, while a reader from Santa Monica cautioned: “Harry Chess is your Henry Miller. Squeamish souls had better look elsewhere. Of course you may be banned eventually (by jealous witches).” In the November 1965 issue editor Polak reported, in answer to a reader’s query about the popularity of the previous issue, that “the most violent reactions came about Harry Chess. About 80% made cancellation threats if we dropped him and the other 20% threatened to cancel if we did not drop him.”