VICIOUS AND IMMORAL

VICIOUS AND IMMORAL

Homosexuality, the American Revolution, and the Trials of Robert Newburgh

by John Gilbert McCurdy

Johns Hopkins Univ. Press

376 pages, $34.95

MOST PEOPLE think the Irish appeared in America in the 19th century, when famine forced millions of people to flee Ireland for the New World. But the truth is that the Irish were here long before that, and they belonged to a very distinct social class called the Protestant Ascendancy: the Anglo-Irish who comprised the British Army, keeping order in the colonies. The 18th Regiment was even called The Royal Irish and was stationed for the most part in a large barracks in downtown Philadelphia, where they wore handsome uniforms, lived with their wives and children, went to the theater, and got along well with the local colonists, who footed the bill for their presence.

In the 1770s, being in Philadelphia was a lot better than being sent to the frontier. Illinois, for example, was so inhospitable for the Anglo-Irish that they considered it as bad as Senegal. But in Philadelphia, at that time the largest city in the colonies, they could enjoy life a bit more, though all this did not prevent the boredom that pushes many a peacetime army to cause trouble. They also had to deal with alcohol, poverty, and venereal disease (without penicillin). In his new book Vicious and Immoral, John Gilbert McCurdy reports on at least one case of child abuse whose details are still sickening to read about. And then there were the class resentments that the “subalterns” (anyone below the rank of captain) felt vis-à-vis the officers who outranked them. As one of the sergeants said about the City of Brotherly Love: “The men were always Murmuring.”

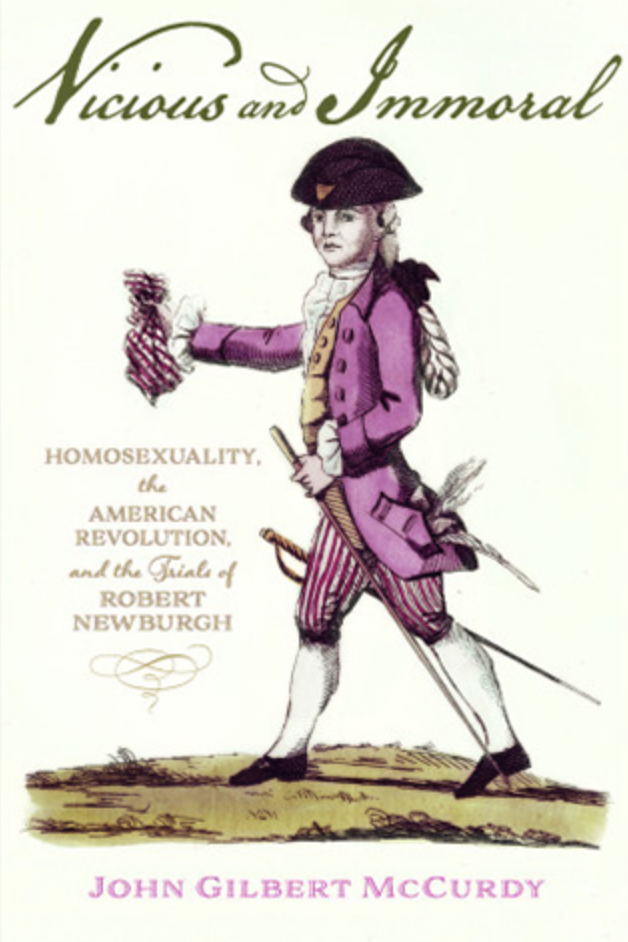

There was one other thing that marked Newburgh as a homosexual in the eyes of Captain Chapman, one of his two chief accusers. One day after Newburgh’s arrival, Chapman was out walking with a fellow officer when he galloped by looking, in Chapman’s words, “More like a fashionable Groom or Jockey” than a clergyman. Chapman described his garb during one of the trials that Newburgh would later initiate to clear his reputation: “Close Light Coloured Surtout, with a Scarlet or Crimson falling Collar, with a round Buck Hat, perfectly in the Stile of a Groom.” Chapman claimed that “at other times he has seen him in the Barracks and streets at Philadelphia in a Dress that had not the Least resemblance to that usually worn by [a]Clergyman: one Dress that he has seen him in, as mostly as he can recollect, is a Light Coloured frock made of Bath coating, Close Buck or Lambskin Breeches, white Silk Stockings and a Smart Fashionable Cocked Hat, in short what is now termed a Maccaroni Dishabille.”

White stockings were newly fashionable then, and so was the Maccaroni—a term for men dressed in spots and stripes and other outrageous clothes, who were precursors of the English dandy—not quite cross-dressers but men dressed to get attention. At that time, as McCurdy points out, what one wore was related to the social order and was essential to the maintenance of the British Empire, which may have been another reason Captain Chapman was appalled by Newburgh’s get-up. The irony is that the uniforms worn by the Royal Irish—copiously displayed in this beautifully produced book—were so gorgeous that there’s something incongruous, if not sad, about dressing like a popinjay only to go into battle and get blown apart. The British grenadier, a fashionista’s dream, wore a hat as tall as a Pope’s mitre—all blown to smithereens during confrontations with the American rebels in Concord, Lexington, and Boston. The rumor that Newburgh slept with his servant, along with his taste for fashionable dress—and, one suspects, a superior education and social status relative to the two ambitious captains, Batt and Chapman, who had classified Newburgh as a buggerer before he even got off the boat in Philadelphia—makes for a story as gripping as The Children’s Hour or even Othello.

The heart of Vicious and Immoral is the sequence of trials initiated by Newburgh to clear his name. In those days, if someone called you, say, a witch, and you did not respond, it was taken for granted that you were a witch. Failure to contest the charge was an admission of guilt. And so, Newburgh sued Captain Batt for what we would call defamation. Then Captain Chapman sued Newburgh for perjury and other charges that went back and forth and culminated in two court-martials, one in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, the other in New York City. There was also a trial of an enlisted man whom Newburgh, as his chaplain, had tried to help, giving rise to homosexual innuendo, and still another for child abuse that somehow involved Newburgh because of a remark he allegedly made about it. At a certain point the trials begin to blur. One, for instance, was about a captain’s refusal to assign Newburgh the rooms in the barracks that the chaplain felt he deserved—rooms that happened to be near the outhouse, which was rumored to be a pick-up spot (does anything change?).

This book contains both transcripts of the court proceedings as kept by the British Army and McCurdy’s commentary on them. At first Newburgh’s legal strategy was to track down the particulars of a sexual act he was accused of so that he could refute it. When that went nowhere, he switched to a defense of his moral character, which should have cleared his name as well, since it was assumed that a person of good character could not be a sodomite.

All this was happening, it should be mentioned, on the eve of the American Revolution. General Gage, the man who promised King George III that he would keep the colonies in Britain’s hands, had many things on his mind, so it’s remarkable that he responded to Newburgh’s petitions for a full court-martial while having to decide where and when to move his troops to suppress the nascent uprising. Newburgh was concerned with clearing his reputation, the general with keeping the colonies in British hands. It is a wonder that he answered Newburgh’s letters at all, but he did—with admirable patience and courtesy.

This moment in time leads McCurdy to expand his inquiry with the question: Did homosexuality have anything to do with the American Revolution? It seems at first a stretch to link the two, but McCurdy has a case. The two men who befriended Newburgh were both subalterns. One of them, a man named Fowler, insisted that Newburgh clear his name, because only then could they remain friends. But one wonders if Fowler was not using this challenge to Captains Chapman and Batt to torment his superiors. Fowler not only testified in Newburgh’s defense; he married an American woman and became an American after the Revolution, which raises the possibility that Fowler was just using his testimony to challenge the British occupying force.

And there’s more. The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, McCurdy stresses, were both products of the Age of Enlightenment, as were the French Revolution and English philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s argument that there was no reason to punish homosexuals. (Thomas Jefferson disagreed, and recommended castration.) In a fascinating epilogue, McCurdy traces the parallel tracks of homophobia in English and American culture. There were no polls at the time of the American Revolution, but he makes the case that in the 1770s and beyond, the new nation did not really care about buggery in the way the English did. There were more important things to deal with, which led to a vaguely tolerant and more relaxed attitude toward homosexual relations.

It’s remarkable that England executed men for homosexuality for many years—unlike France, for instance—and remained virulently homophobic until and beyond the trial of Oscar Wilde. English noblemen had to live abroad if they were suspected of same-sex desires. In the U.S., it was more “Come back to the raft, Huck honey” (the title of Leslie Fiedler’s famous essay on the homoerotic strain in American literature). The frontier meant that you could always go west. It wasn’t until the 1950s, when Senator McCarthy conflated homosexuality and Communism, that the two countries began to share the same level of homophobia, though the U.S. never made sodomy a capital offense.

So, although it’s hard to say that homosexuality impacted the Revolution directly, anger against the British (and their laws) and a general tolerance brought about by freedom and sheer space conspired to ensure that the colonies did not make such a big deal about what men did with one another. As for Reverend Newburgh, was he even gay? Historians are helpless without records, and at a certain point after the court-martial in New York, our hero simply fades from the page. On May 13, 1775, Newburgh (who had previously expressed a dislike of America) sailed to London, switched his commission from the 18th to the 15th Regiment, and sailed back to America in time to participate in the British invasion of New York. After that, he saw duty in the Caribbean, where, after the British defeat in Grenada, he resigned his commission and took a post as a hospital chaplain on the island of Belle-Île-en Mer, a French territory off the coast of Brittany. And there he remained until his death in 1825.

In the end, one doesn’t know what to make of him. Was there something narcissistic about the clothes, even the insistence on clearing his name? Was he just a drama queen? One can only imagine what General Gage thought of his case; presumably he wished it would disappear. The transcripts do not make everything clear. For instance, the court-martial found that Newburgh had lied when he said that Captain Chapman had offered to settle their case out of court. But what was the meaning of the comments the chaplain made about the awful child abuse trial that preceded his own litigation? He remains somehow an elusive figure no matter how much sympathy one feels for what he had to endure.

But the pleasures of Vicious and Immoral do not depend on what we think of Newburgh. McCurdy’s slice of history is written with an eye for detail that puts us back in an era that is largely ignored these days. It’s not just the central story that engrosses us; it’s the wealth of detail, the re-creation of a time in American history when Britons were turning into Americans. When Newburgh arrived, the British clergy was already associated with same-sex activity, and so was the Army. Soldiers stationed in London were known to sell their favors to the rich and entitled (a practice that, as readers of J. R. Ackerley’s classic memoir My Father and Myself already know, lasted to the late 19th century, when Ackerley’s father was kept by a Belgian aristocrat who later gave him his start in business).

Then there was Isaac Bickerstaff, who served in the Royal Marines during the Seven Years’ War—an Anglo-Irish lieutenant who, upon retiring, moved to London and started writing comic operas like Thomas and Sally and Love in a Village. In 1772, at the height of his success, newspapers reported that Bickerstaff “grew enamoured, the other night at Whitehall, with one of the Cenitnels and made love to him.” Newburgh would have understood, McCurdy writes, that the gravity of this incident was not just that Bickerstaff had committed buggery but that he had made the Army an object of ridicule. A piece of doggerel mocking “these enlighten’d times” in which Bickerstaff did “for grenadiers imprudent burn” even asked:

Of manly love, ah! Why are men ashamed?

A new red coat, fierce cock and killing air

Will captivate the most obdurate fair.

It’s nice to know there were all levels of response to the charge of buggery, including mocking and sophisticated ones, though Newburgh’s accusers were not among the latter. After the court-martial’s mixed verdict, they tried to get him transferred to—where else?—Illinois.

As for Newburgh, one hopes he found happiness, but we shall never know. McCurdy never takes a definitive position on his subject’s homosexuality. Reading this book, one is hard-pressed to say; but I suspect he was. That’s based in part on the way McCurdy ends his book with what happened to the various characters in this legal donnybrook. Newburgh’s detractors, Batt and Chapman, got married to women, rose through the ranks, and served in other theaters. But, McCurdy writes: “the former chaplain’s life after the l8th Regiment took a different route than either the captains or the subalterns. He never married or had children; he neither settled down in England nor pioneered a new life on the American frontier. Instead, Robert Newburgh’s manhood was queer, and it followed a separate path.” Like Bickerstaff—or Lord Byron, for that matter—he ended up an exile from his own country. Newburgh wound up off the coast of Brittany, taking his secrets with him. He wandered off the pages of the historical record into oblivion, from which Vicious and Immoral has now rescued him.

Andrew Holleran’s latest novel is The Kingdom of Sand. His other novels include Grief and The Beauty of Men.