IN THE 1990s, in a used bookstore in South Africa, journalist William Pretorius stumbled upon a battered copy of a novel titled The Gay Sarong published in 1925. Intrigued, he started reading the story of a man who gives up his wife—and women—for a handsome younger man. Pretorius thought, and wrote, about this chance encounter as if he had found a message in a bottle, having unrolled a cri de coeur from the past. Who was this American author named Harry Hervey? And could this astonishingly frank book about an obviously gay man really have been published in the 1920s?

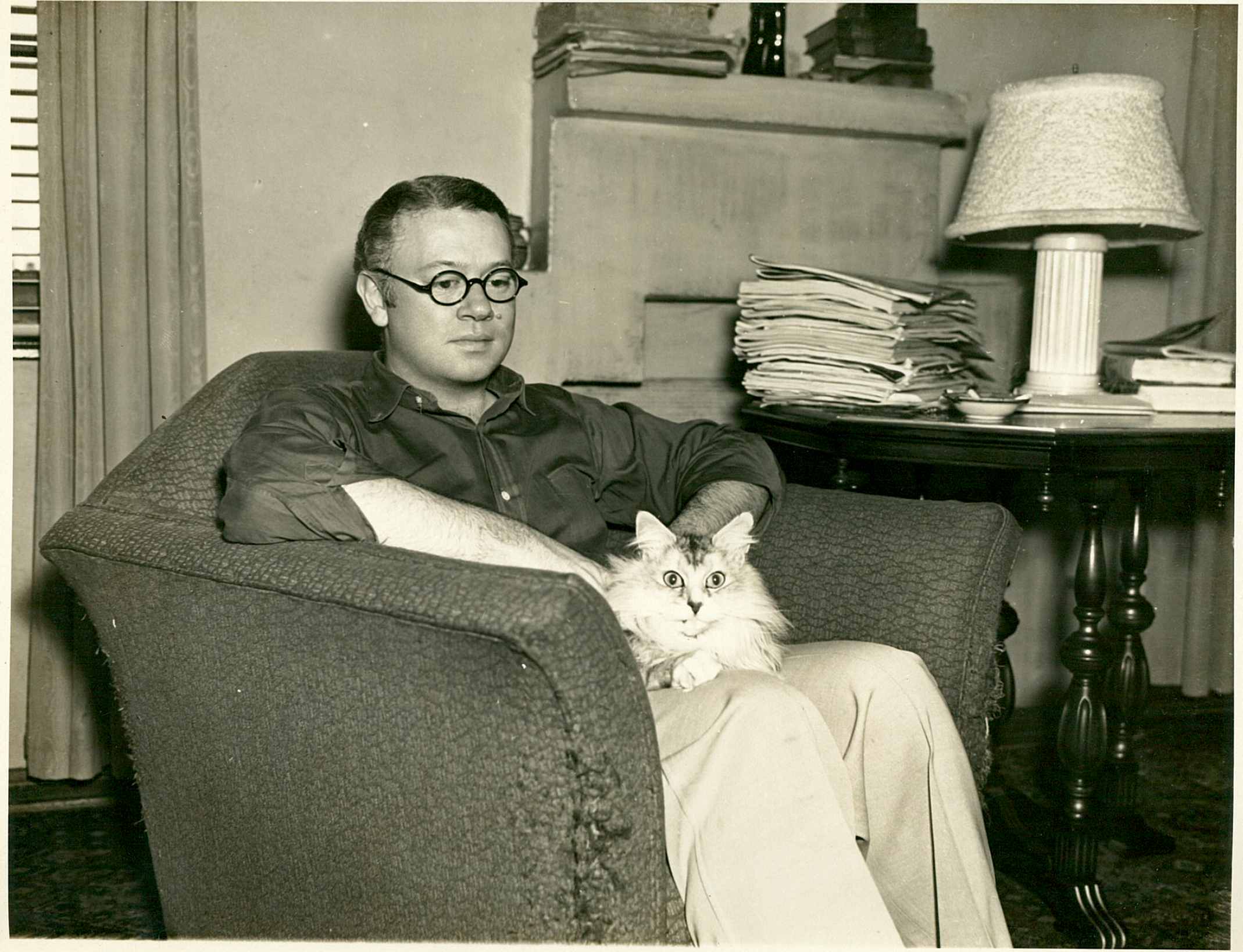

That used to be the standard reaction; but more and more we’re coming to realize that many colorful gay men and women were on the scene long before Stonewall, influencing popular culture, even producing works with same-sex situations. One out fellow now almost totally forgotten was a man whose life spanned the first half of the 20th century: Harry Hervey (1900–1951), author of The Gay Sarong, was not just a bestselling novelist, but a screenwriter, playwright, and adventurer. Reading his works, three of which are now back in print (with a biography looming), you’ll find a discernible gay fingerprint on almost everything he touched.

Harry Clay Hervey Jr. was born in Beaumont, Texas, on November 5, 1900, to Harry Clay Hervey Sr. and his young wife Jennie. Harry Sr. was a dutiful father until he vanished for unknown reasons, abandoning his family along with the Hervey Hotel Company, which had properties in Florida, Alabama, and Texas. Harry Jr. grew up in hotel lobbies, watching the comings and goings of beautiful women and handsome men. He read voraciously, swooning over pictures of half-naked men in faraway places like Angkor Wat. He adored exotic garb and became fascinated with women, their wardrobes, ways, and wiles. His mother Jennie enrolled her effeminate boy in military school, snatching him away from a school at Sewanee, Tennessee (which he would later use as a setting for a homoerotic story), to Atlanta’s Georgia Military Academy, from which he graduated just before World War I. (Jennie would wisely give up reforming her son, eventually living comfortably with him and his lover, shaving years off her age to become, as some reporters called her, the youngest mother on record.)

Harry’s academic career had not been distinguished, but amazingly, at sixteen, he sold a lurid adventure story to a magazine edited by cultural critic H. L. Mencken. Harry cut his teeth on Black Mask, one of the greatest of pulp magazines, where other young writers like Dashiell Hammett honed their skills. Harry published some half-dozen stories about far-off places, most with allusions to damnation and devils in their titles. In his tales, men seemed to avoid women, preferring the company of other men. In the highly camp “More Deadly than the Viper,” for instance, the hero finds his male pal and other once virile men virtually emasculated by a seductive vamp; he rescues them, banishing the evil woman, who turns into a bat, allowing our hero and his buddy to ride off into the sunset together, a theme the author would return to again and again.

By his mid-twenties, Hervey had published two adventure novels—one with a character named Dickie Manlove, “a delicious boy”—and a book about his travels around the world. In Where Strange Gods Call, he extolled the blue road of romance (blue, as in blue movies, apparently). While most critics chalked his antics up to his youthful search for high adventure, his gay male fans could read between the lines to decode what was going on. His description of picking up a kilted Scotsman and spending the night with him “where the fairies danced,” as well as being robbed by “naked men” who had picked him up in anticipation of a good night together, leave little to the imagination. He hinted again and again about his attractions to men, admitting he was not a 100 percent red-blooded male, that he was terrified when a woman made sexual advances to him, and that chastity was a tragedy for men, especially handsome ones. He bragged to reporters about what happened when he was denied entry to a harem in Cairo, telling how he blithely switched sexes by donning women’s clothes convincingly enough to get in. “I crept inside my characters and looked out through their eyes,” he’d say later of his writing. When he wasn’t describing men running off with other men, he was writing about women desiring them, peering out through their eyes as he used language to parse male beauty.

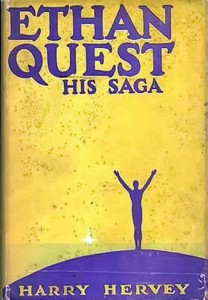

Critics loved Harry Hervey and called him a lush, mad, and sex-crazed; but nearly all missed the references to his homosexuality. It’s almost as if he was trying to out himself, but it just wouldn’t take. This tendency reached a peak in his 1925 novel Ethan Quest (called The Gay Sarong in the UK edition), an autobiographical Bildungsroman of a young boy growing up in Savannah, Georgia, where Hervey had moved to join his mother working in the DeSoto Hotel. At Sewanee, Ethan falls in (and in love) with his roommate Eric. Ethan goes out with girls only because Eric does, but he is repulsed by them; instead he longs for “the touch of his friend. Blond, brown friend sitting in the room. Or lying beside him in the darkness.”

Critics loved Harry Hervey and called him a lush, mad, and sex-crazed; but nearly all missed the references to his homosexuality. It’s almost as if he was trying to out himself, but it just wouldn’t take. This tendency reached a peak in his 1925 novel Ethan Quest (called The Gay Sarong in the UK edition), an autobiographical Bildungsroman of a young boy growing up in Savannah, Georgia, where Hervey had moved to join his mother working in the DeSoto Hotel. At Sewanee, Ethan falls in (and in love) with his roommate Eric. Ethan goes out with girls only because Eric does, but he is repulsed by them; instead he longs for “the touch of his friend. Blond, brown friend sitting in the room. Or lying beside him in the darkness.”

Hervey’s talisman for romance is a “gay sarong” given to the young boy by a sailor in Savannah. Many of his other books obsess on splendid oriental dresses, cloths, shawls, and fabrics. He draped his apartment in Savannah with them. A New York journalist who went down to investigate reported: “Hervey is a dark young man who wears on his hand a ruby ring presented to him by a beneficent oriental potentate. He showed us a white robe embroidered with a golden peacock and lined with saffron, that should be worn by [silent film actress]Pola Negri. We forgot to ask him if he ever wears it himself.” She was, of course, trying to suggest that Hervey might be gay. He entertained in costume, and images exist of him in oriental fabrics and an ornamental headdress, a creature of exotic splendor and indeterminate gender.

Ethan only marries Leila because, lonely, he has no one left. He realizes the falseness of it all, saying to himself: “Marry her! Let her breed your children. … But you know she will break you! So marry her and watch the slow death of Ethan Quest!” Leila finds the gay sarong hidden away, realizing it is a metaphor for all his “queer” ideas. Gay readers at the time must have seen what straight readers could not. With coded references to Whitman and Melville, Ethan comes to realize that he’s just not the marrying kind. He has a greater love for “mankind,” he says, really meaning—wink, wink—actual men. Hervey skillfully equates being gay with being an artist. Marrying and giving up his creative nature has nearly killed him and made Leila miserable. Only by following his true nature, that of the gay sarong, can he be happy. His takes off to the South Sea Islands that Melville wrote of and finds an adhesive partner celebrated by Whitman. He meets a handsome native boy and they spend their lives together, “the two of them, priest and chela, offering the gay religion of song.”

Before the book came out, Hervey had also left Savannah for “the outermost isles,” like Ethan, with an underage boy in tow. He somehow had convinced teenage Carleton Hildreth’s parents of his need for a secretary and traveling companion for his trip to Indochina. Having dreamed of going to Angkor Wat since boyhood, he conned the Cosmopolitan Book Corp. and McCall’s magazine into funding his search for a lost ruin in the middle of the jungle that no white man had seen for centuries (or since 1914). He was sure he’d be able to decode and solve the mystery of the builders of it and Angkor Wat. Once there, true to form, he not only found adventure but also uncovered historical evidence of male homosexuality flourishing in the fabled past. He proudly (and a bit cheekily) announced that he had deciphered the riddle of the temples and their dizzying array of cone-shaped towers.

“I had a new picture of Angkor … Angkor in the shadow of lingam,” he gushed, using a Sanskrit word for penis. The secret of the universe was revealed. “Brahma the Creator and Siva the Destroyer … relentlessly chanting the creed of the phallus.” And if that weren’t audacious enough—finding infinity in the phallus—he ended King Cobra with the image of a powdered gay male prostitute asking him for a light. He also made it pretty clear that he enjoyed assignations with heavily muscled native men along the way.

The book came out almost simultaneously with a novel inspired by the trip: Congaï, which was the first book about Vietnam by an American. In it, we meet Hervey’s first real flesh-and-blood heroine, Thi-Linn, the daughter of a French man and a native mother. Used by one man after another, she comes to personify her abused country, but she rises to meet her fate in tragic splendor.

Once back in America, Carleton and Hervey continued their adventures—this time on Broadway. Carleton was taking acting lessons to get rid of his Southern accent and was cast in a few pretty-boy parts. Hervey and he put their heads together to turn the novel Congaï (pronounced Conguy—technically meaning a young girl, but subtly referring to native “temporary wives”) into a play. It had a successful run, directed by the young Rouben Mammoulian, who would soon have a huge impact on Broadway musicals and films. Critics lauded it, not only for its frank handling of sex but also for its exposé of imperialism, showing it up for its subjugation and exploitation of “darker” races by Europeans.

By this time, Carlton and Hervey were being whispered about in cloistered and closeted Charleston, South Carolina, where they had gone to live after Savannah. Hervey got back at the social set by using their city as the setting for Red Ending, a decadent Jazz Age novel with a pronounced gay subtext. By the time it was published—just as the stock market crashed in 1929—Hervey, not quite thirty, had seven books and a Broadway play to his credit. Thereafter he would support himself through films.

HERVEY HAD BEEN GIVEN the royal treatment by Samuel Goldwyn a few years earlier, having been imported to Hollywood to write the screenplay for the exotic Gilda Gray, inventor of the shimmy. “Entirely aside from his standing as a novelist and a dramatist, Hervey has a high academic standing as an Orientalist,” Goldwyn wrote. “Naturally, we depended on him a great deal not only for the continuity, but also for the local color.” The resulting film was The Devil Dancer, based on one of Hervey’s prize-winning short stories, a silent classic that’s now lost. To maximize the exoticism of Gilda’s character, Hervey loaned her his own headdress.

More films with femme fatales and exotic settings followed. His rewrite of the film The Cheat, starring Tallulah Bankhead, barely got by the censors, and once the new moralistic Motion Picture Production Code (the notorious “Hays Code”) took effect in 1930, the film was banished from distribution, appearing only decades later in a CD collection of pre-Code Hollywood.

After the success of Congaï, Hervey and Carlton co-wrote a play based on a prison they had visited in Indochina whose homoerotic scenes obsessed Hervey. But problems arose: his work, titled The Iron Widow—a slang term for the guillotine and a symbol of Hervey’s recurring fear of castrating women—was much too gay for the stage. Helen Menken, who had played the title role in Congaï, had earlier been arrested, and the play she was in had been closed down because of its frank portrayal of a lesbian. Hervey and Carleton’s play focused on male homosexuality; the producer got cold feet and withdrew The Iron Widow from production.

But Hervey was not about to back down and remained determined to get his story before the public. The Well of Loneliness had just been cleared of obscenity charges, so Hervey turned his play into a novel and got around the censors in that way. If readers of The Iron Widow thought something funny was going on in the pages of Ethan Quest, with its lavender and yellow dust jacket, there could have been no doubt about this one. Its dust jacket proclaimed one character to be an “invert” and implied that Hervey had “seen it all.”

Set in French Guiana, the story features a plot taken from Condemned to Devil’s Island, by Blair Niles, who wrote the classic gay novel Strange Brother. (Interestingly, it was announced that she and Hervey would write a play together, but nothing came of it.) It’s a story of an undercover, obviously gay prison inspector coming to investigate conditions on Devil’s Island. Delphine, the prison warden’s wife who seduces male inmates for her pleasure, hates him and all gay men, whom she sees as threats to her game. It’s a lurid, depraved, and compelling tale, and what Hervey did with it is nothing short of astonishing, subverting the stereotype of the depraved sex pervert. For instead of the story being about a man saved from the horrors of homosexuality by the love of a good woman, a young boy who’s in the grips of a sexually predatory woman is saved by the love of a good man. “Necessity is the mother of inversion,” quips one of his characters, referring to male sex in prison. You can almost hear Hervey and Carleton laughing in the background.

The book did well enough to go into a second edition during the Great Depression, though copies are hard to find. It was republished in the 1950s under the camp title She Devil, with a picture of a shirtless man backing away from a voluptuous vixen on the cover. Astonishingly, neither it nor any of Hervey’s other gay works have received any scholarly attention. None appears in any compilations of “lost” gay writing; his name is never mentioned.

In Hollywood, he and Carleton tried to get The Iron Widow filmed. They never succeeded—for numerous reasons, and despite their willingness to tamp down any evidence of homosexuality. However, the novel Congaï was sought by many actresses and producers, including Irving Thalberg, but enforcers of the Code were on to Harry. The heroine, Thi Linn, was doomed because she was half Vietnamese. Hervey acquired a showy house with the obligatory pool—around which Carleton, in his formidably form-fitting swim trunks, strutted and posed like a peacock. Hervey was often out on the prowl, on streets and docks picking up men.

In his years in Tinseltown, Hervey wrote scenarios and screenplays for films with actresses like Bankhead, Loretta Young, and other stars of the day, vehicles with names like The Devil’s in Love, The Devil and the Deep, and Passport to Hell. His greatest success by far, however, was the scenario he created for the iconic 1932 film Shanghai Express, directed by Josef von Sternberg and staring Marlene Dietrich. While the film duplicated some situations from his early short stories, its strongest feature was its heroine. The figure of the Magdalene—a woman torn between sexuality and sanctity, between sinning and sainthood—had marked his work and would continue to do so. Here she is in full flower; the character portrayed by Dietrich is named Magdalene.

The film brought Hervey fortune and fame, but they proved short-lived. He trod the same path of many a writer before and after him. His success went to his head; he drank and celebrated too much; his work fell off; he fell into debt; the IRS began to hound him. A serious scenario he sold was inverted into a comedy—The Road to Singapore, the first of the many Bob Hope and Bing Crosby “Road” films, which earned him not a cent. He knew he had to get out of town when a man who worked in his uncle’s upscale El Encanto Hotel, with whom he had carried on a casual affair, began to blackmail him. To escape the situation, Hervey had to pawn the ruby ring that an Eastern potentate had given him.

Broke, back in Savannah, where his mother, working at the DeSoto Hotel, loyally supported him and Carleton, Hervey hit the darkest part of his life, but did some of his finest writing. His tale of a girl from the wrong side of the tracks in Savannah, The Damned Don’t Cry, despite its melodrama, made critics take notice of a serious novelist taking on social issues. (Sold to Hollywood, only its title survived in one of Joan Crawford’s most scenery-chewing roles.) His next novel, School for Eternity, was his masterpiece, a sophisticated meditation on the sacred and profane sides of life, with characters crossing destinies on a fictional Caribbean island. (Although Hervey had included a gay character and subplot in his encompassing view of humanity, it was cut from the condensed version in the magazine Omnibook.)

Two more novels followed in rapid succession, the final one based in Africa and dramatizing a white woman killing her wicked husband to save a noble black man—not the most popular thing for a Southern writer dependent on book sales to be doing in 1950. Hervey had come a long way from his lurid, winking novels of gay adventure to serious considerations of the human condition.

An inveterate smoker, he developed cancer and died on August 12, 1951, just as the third film based on the scenario for Shanghai Express hit the screens. Carleton lived on, working as a proofreader for the Savannah papers, a job for which Hervey had prepared him. After his death, all their materials landed as trash on the street.

It is tempting to wonder what would have happened if Harry Hervey had lived in a more tolerant age. Would he have been more successful? Had an easier life? Been better remembered? And yet, I think Hervey needs no explanations or apologies. Like his lustful men and his unapologetic women, he might have been damned by the times he lived in, but that did not deter him. He literally wrote his own epitaph, saying he was content with the adventures and life he had: “Mine has been a long journey, to the uttermost hinterlands, and my eyes and heart are filled with what I have seen. One cannot have looked behind the mask we have put upon death, and found there the face of god, without being invested with the highest inspiration, the deepest humility.” You can read it in his books, see it in his films, or carved on his tombstone, under which he rests in Savannah’s Bonaventure Cemetery.

Harlan Greene is the author of What the Dead Remember and other novels. He is head of special collections at Addlestone Library at the College of Charleston, SC, and author of the forthcoming The Damned Don’t Cry, They Just Disappear: The Life and Works of Harry Hervey (University of South Carolina Press), from which this article is excerpted and adapted.