MARTIN ASTON is the author of the recently published book Breaking Down the Walls of Heartache: How Music Came Out (Backbeat Books), a 600-page compen-dium of popular music history from 1907 to the present, specifically the presence and influence of LGBT singers, songwriters, producers, and entertainers across this century. The book is organized chronologically and offers a brisk tour of popular music and its gay movers and shakers for each decade starting in the 1920s.

Aston’s previous book, Facing the Other Way: The Story of 4AD (2013), spotlighted the many bands produced under the 4AD label. He has written about popular music for over thirty years, contributing to The London Times, The Guardian, and most other major periodicals in the UK. Aston lives in south London.

This transatlantic interview was conducted by phone in May.

Gay & Lesbian Review: The first question that comes to mind is about the book’s fascinating title, Breaking Down the Walls of Heartache. Where does it come from?

Martin Aston: The title is a song from 1968, by Johnny Johnson and the Bandwagon, and it was in the genre here [in the UK]called Northern Soul, which was a kind of soul music with more of a dance emphasis. So on its way to disco, and it was a big hit in Britain. Of course, the song has nothing to do with anything LGBT; it’s just a song title, but it seemed so apposite—breaking down the walls of heartache as the process of coming out as gay. Part of me just wanted to call the book How Music Came Out [the subtitle]—just those four words. But a couple of people said, maybe you need something a little more poetic. So that’s why I went with it; it just felt right.

G&LR: Well, it’s a great title. So the book covers about a century starting in the 1920s and goes up through the present time. Did you find any kind of general theme—is it possible to talk about the role that LGBT people have played in popular music, say, as outsiders or radicals during this period?

MA: I would say that is definitely the theme, because due to legal, political, and social restrictions for most of this period, you couldn’t say that you were gay or lesbian. So when people were being bold about it, that was how. They were not allowed to express it in any other way than in music, which was an opportunity to reach under the radar. Nobody at the time would say “I am gay. I am lesbian.” Everything was done in code. These artists were taking risks. They were outsiders and they had a lot to lose—but in another sense you might say they had nothing to lose.

G&LR: Are there any particular pioneers going way back into the early period, before World War II, that you would cite?

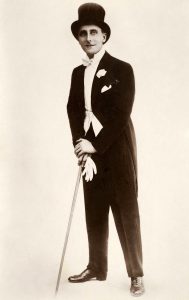

MA: For me, where it really starts is the first obvious declaration in 1907, and it was by a British music hall singer by the name of Fred Barnes, who was so out in his personal life—he apparently had a penchant for the armed forces—that he was banned from going to what was called the Royal Tournament, which was an annual performance by the armed services. When he would come out on stage, people would shout out, “Hello Freda!” The song he made famous was called “The Black Sheep of the Family,” and the opening line was “It’s a queer, queer world that we live in.” One of the other lyrics was “Some get all of the sunshine, others get the shame,” which was a code word for being gay—but only for those in the know. So long as he didn’t do anything to create any further trouble, he was fine. There was a kind of novelty aspect to him in an era when you had male and female impersonators. In a way he was inspired by a female impersonator. In a way he is impersonating a woman impersonating a man.

G&LR: Sounds like Victor/Victoria.

MA: That’s kind of the world he’s in. But later on in his life, he was caught drunk driving through Hyde Park in London in the company, supposedly, of a topless sailor. He became a celebrity in the papers, but his career never really recovered, and he drank himself to death. But that’s the earliest example of a song that was clearly about being gay. He identifies as the “black sheep of the family,” but sings that one day the black sheep will become the whitest sheep of all, i.e., he would be redeemed, and it would no longer be seen as a crime. He was incredibly pioneering.

G&LR: The first decade you cover is the 1920s, which was certainly an interesting era; am I right?

MA: The era after World War I was marked by a much more liberal atmosphere in European and American cities. The Harlem Renaissance, for instance, was not only about literature but also about music. In music you had artists like Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith, who sang about bisexuality. They would never label it that way, but there were songs about other women and, though they were both married, both were known to have female lovers. Ma Rainey would sing about them in the blues. And you even had men like George Hannah singing “Freakish Man Blues.” So there was a way of coding it. In the 1920s, in places like Harlem and Greenwich Village, you had masked balls where people would dress up as the opposite sex. There was a famous song that was covered by different people called “Masculine Women and Feminine Men,” and the chorus goes: “Who is the rooster, who is the hen?”

What happened at the end of the 1920s was the Great Depression, and with it came a religious and conservative backlash. By 1934, Hollywood had its new code of conduct [the Production Code], which banned virtually all sexual content. In music as well, freedom of expression swung back. It’s said that the two most liberal decades of the 20th century were the ’20s and the ’70s. In the 1930s you’ve got Noel Coward and Cole Porter and lesser-knowns like Bruce Fletcher. When you listen to Noel Coward today, you think it’s obvious, but at the time, people didn’t know. He never officially came out. Bruce Fletcher was all about double entendres and was incredibly campy in his act. But this was the 1930s, and he found it very hard to hold down a gig, became an alcoholic, and killed himself. He had an actor as a partner. Even Cary Grant had a male partner. But nobody said, “Oh, they’re obviously gay,” unless you were gay and you knew what was going on. It was hiding in plain sight. It was Hollywood. People just let it through.

G&LR: So, things then start to really freeze up in the ’30s and ’40s. Would you say they start to unfreeze in the 1950s, if only because of Little Richard?

MA: I wouldn’t even say that things were freed up in the 1950s, because obviously Little Richard was completely closeted. Not even the 60s. Prior to Stonewall [in 1969], you had someone like Johnny Ray, who had a huge number one hit in the States with “Cry.” He wasn’t yet “rock and roll”; he was a new postwar type of singer; he was extremely melodramatic. Then it came out that he had been fined for—I think he was caught by an undercover policeman at a known cruising spot. It didn’t end his career, but he never really was given the same kind of coverage.

In the 1950s, Little Richard was writing “Tutti Frutti,” which was an ode to gay sex. “Tutti frutti, good booty.” I mean, that’s what he’s talking about. But the record label wouldn’t let that [“good booty”] go through. But nobody even knew what “gay” meant; people didn’t understand the link. Only people who saw him in clubs would know. He came out of the Southern drag scene. He even had a drag alias, Princess Lavonia. The “fruity” part came from Carmen Miranda, who was a role model for drag queens, who would impersonate her onstage.

One thing to mention in the ’50s was a female trio in Baltimore called the Roc-A-Jets. Unfortunately, they never made any records. When you see a photograph of the band, the three women, they look like Buddy Holly and Roy Orbison. They’re dressed in black and white pants and shirts, and they had fans, apparently, who dressed like them in lesbian clubs. (There were gay and lesbian clubs around that managed to survive because they paid off the police.) So, you just have to look at the Roc-A-Jets, how male they look. And they were playing lesbian clubs; they would play night after night. They never made any records because two of them were single mothers and divorced, and they couldn’t take the time off to make a record.

G&LR: Let’s move into the 1960s and maybe even the ’70s, so that we can talk about a more open kind of expression.

MA: The bridge from the ’50s to the ’60s was the start, certainly in British pop music. The British answer to rock and roll was kind of engineered by gay men. You had Larry Pfqueer ounds, who was behind people like Billy Fury and Tommy Steele, who were kind of British answers to Elvis Presley. Then you had Brian Epstein, who managed the Beatles. He smartened them up and cut their hair and put them into suits. It was the early days of “queer eye for the straight guy.” Epstein knew how to give people an image. So, the Beatles look great, and then you’ve got the Rolling Stones, who have a kind of androgynous and subversive image. Even though the Stones’ manager wasn’t gay, he really understood. He put the Stones in drag in the mid-’60s because it was seen as sort of provocative and against mainstream society.

G&LR: You mentioned Stonewall as a milestone. Do you think popular music, such as that of the Rolling Stones, may have played a role in the political upheaval that took place in the late ’60s and ’70s?

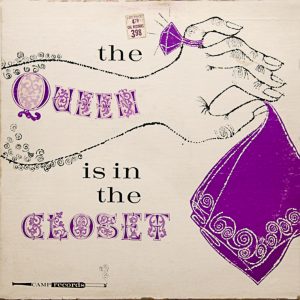

MA: Well, it was all in the air. Still, the tide isn’t turning in the ’60s, really. The only really out gay pop music was this label called Camp Records, which put out a two albums—one is titled The Queen Is in the Closet— and singles of party music with songs having titles like “Rough Trade” and “Stanley the Manly Transvestite.”

G&LR: What about Lou Reed? He was shaking things up in this era, wasn’t he?

MA: Lou Reed came along: the Velvet Underground. So you’ve got a song like “Sister Ray,” which years later he starts saying is about a drag queen and sailors, and they’re shooting up smack and everything, but you listen to the lyrics and you don’t know that Ms. Ray is meant to be a drag queen. When suddenly he’s famous in the ’70s because of his association with David Bowie, then he’s talking about it.

But I think David Bowie broke new ground, certainly. I mean, he was wearing a “man’s dress”—not a woman’s dress, but what he called a man’s dress, which was almost like a medieval type of dress—on the cover of an album in 1970, and he’s going down to gay clubs. He’s playing with it; it’s like chic. It’s that kind of bisexual chic. Though he said “I’m gay” in an interview, he meant to say “I’m bisexual.” Of course, he was married with a kid, so there was a certain kind of a safety net around that. Bowie and Jagger became mates years later, but I think Bowie would have seen what was going on in pop music [on his own]. He was aware of the sexually charged lyrics of Jacques Brel in France.

So Bowie was drawing on all these different threads and pulling them together, and then he found out about the Cockettes in San Francisco, who were wearing drag and glitter. In a sense, that’s where glitter rock in America first appeared. It became glam rock, which is the term here. Bowie started to notice different things going on, and tried to be provocative and push the boundaries, and one way to do that was with sex and sexuality. It was the right time, and he read the signs and concluded that there was room for bigger, more theatrical, presentations of pop music.

G&LR: Speaking of which, what about Sylvester as a phenomenon of this era?

MA: Sylvester was a member of the Cockettes; he was the first black member and the only one with a proper voice for performance. He was radicalizing San Francisco in a kind of explosion. He was out from the word go. Not that he ever wrote songs that said “I’m gay and I’m proud.” He didn’t get political, but if you saw him and his album covers, it was obvious; he was not hiding.

You also had the singer Valentino with the song “I was born this way” in 1965—long before Lady Gaga—which was then covered by C. Bean. I don’t know if you’ve heard of Archbishop Carl Bean. He was a singer in the late ’60s, early ’70s, who had his own church. There were two versions of “I Was Born This Way”—both sung by male singers—which sold some copies in the ’70s, but they weren’t considered hip. The disco songs that were huge hits were by female singers with titles like “I Will Survive,” “Don’t Leave Me This Way,” and “Never Can Say Goodbye.”

G&LR: Good old Gloria Gaynor.

MA: Gay men wanted women to be the mouthpiece for them. They didn’t want other gay men to do it. This is the interesting thing. When gay men made a statement in their music, the gay public wasn’t particularly interested. They wanted to escape from all the years of oppression and being in the closet, so they just wanted to have fun and disco. On the other hand, the women’s music scene was the kind of a post-folk scene where women made statements. For example, Alix Dobkin had a song with the lyrics “The men are them, the women are we/ And they agree it’s a pleasure to be/ A lesbian in no man’s land.” Indeed the word “lesbian” is all over the record. And these songs sold in the hundreds of thousands, because women wanted validation. Gay men wanted escapism.

G&LR: You mentioned disco—

MA: Which sold not hundreds of thousands but tens of millions of records. Disco was the soundtrack to coming out in the ’70s. It was the soundtrack to being able to go to bars and clubs and not think you were going to be raided, and not think there was going to be anything oppressive about it. Gay clubs were proliferating, as were bars. Well, you’re not going to go to a club and go cruising to sad folk music. Most women were not out cruising in the way that gay men were. There were lesbian clubs, but they were greatly outnumbered by gay male clubs. Gay men were out cruising, taking drugs, dancing, celebrating, and you’re going to need up-tempo music for that. So we’re getting away from the soul music of the ’60s and into the more heavily produced music of the late ’70s, and obviously electronic influences are coming in. Music is becoming sort of more hypnotic or more like drug trips. The disco became a big cauldron of, I don’t know—

G&LR: A cauldron of fun?

MA: A cauldron of fun. Escapism is part of that. What’s interesting is that there was a gay male equivalent of the lesbian music scene—artists with a message who expressed themselves in the manner of, say, Cat Stevens, James Taylor, or Leonard Cohen. These gay artists would include Steven Grossman, who was the first gay man to release an openly gay-themed album on a major label (Mercury), and Michael Cohen, who sang about cruising the New York docks. Their songs are deeply introspective about gay trauma and the loneliness of being in the closet. But nobody wanted to listen to someone sad-talking about being in therapy or feeling blue because they can’t find the right person. That sold very badly, whereas the disco songs sung by women sold fantastically. Obviously they were not only being bought by gay men, but they were the core.

G&LR: Indeed, disco came to be so closely identified with gay culture, but it was also popular in the mainstream—one of the ways that gay culture has penetrated into straight society?

MA: Yes, gay male fashion has set the tone, and the whole rise of the metrosexual has come. The fact that football players care about their appearance and will advertise beauty products! There’s a football team on TV here which is advertising Nivea cream for shaving their chest! It’s totally mainstream. You know, David Beckham is a very famous football player who likes to be pictured in a sarong or talking about grooming products. So many modern male fashions, whether leather or denim, come from the gay scene. In terms of music, not only disco crossed over, but in the late ’70s into the ’80s you’ve got house music and garage. Garage as a genre kind of morphed into house music, but they were both named after famous gay clubs, the Warehouse in Chicago and the Paradise Garage in New York, with DJs like Larry Levin and Frankie Knuckles, who were huge crossover stars, but they got their start in the gay scene.

G&LR: We should probably start to wrap things up. Is there a way to take us from the 1970s up to the present time in a relatively few words?

MA: I think music very much became a mouthpiece for gay acceptance, certainly in the ’80s. You’ve got Frankie Goes to Hollywood and the Bronski Beat. And Erasure. You’ve got British pop bands having huge hits here, less so in the States. I think AIDS created a big backlash and had a much bigger impact there than it did in Britain.

G&LR: Looking at the two countries, it is interesting how British artists have so often been out in front of American ones in taking on LGBT themes.

MA: In terms of pushing things, you’ve got David Bowie and then you’ve got Freddie Mercury, who never came out, but obviously the kind of theatricality and campiness as the front man for a band called Queen was putting it all out there. But yes, you’ve got British artists who were bolder. I think Britain is a more contained country. In America, you’ve got the bicoastal thing, and in between there’s this big Midwestern sway and the religious Right, which we don’t have here. Of course the hip-hop scene and the country music scene have been deeply homophobic, but even that has started to change in the last ten years or so.

In terms of pop music, David Bowie had been around for thirty years and influenced so many other artists. Suddenly there was no shame involved. We had a number one single here with a video set in a gay club by the group Frankie Goes to Hollywood. They’re dressed in leather. He’s celebrating the whole thing. He’s talking about it in interviews. There’s no turning back, you know.