Essential Essays: Culture, Politics and the Art of Poetry

Essential Essays: Culture, Politics and the Art of Poetry

by Adrienne Rich

Edited by Sandra Gilbert

Norton. 352 pages, $27.95

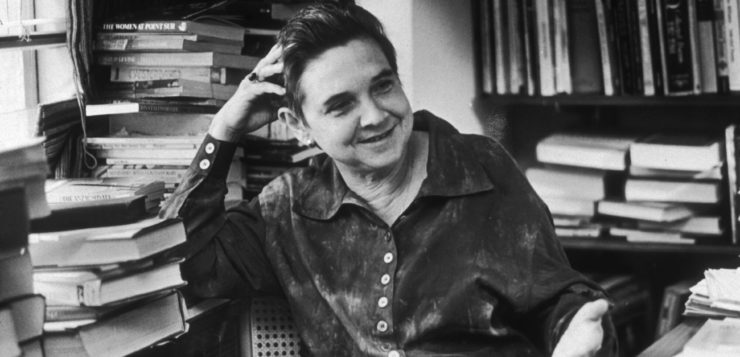

ADRIENNE RICH (1929–2012) was a 20th-century poet who wrote essays and criticism with the same ease and effectiveness that she brought to her major craft. This ability places her in the company of James Baldwin, Gore Vidal, J. D. McClatchy, and a relatively small cohort of others. Another distinction is that Rich, like Baldwin and Vidal, was exceptionally engaged with the issues of the day. These writers—along with Ursula K. Le Guin and a few other so-called “public intellectuals”—were in effect successors to Lionel Trilling and others of the early 20th century. This new generation appeared on schedule; what changed was the subject matter. The Cold War and its precursors and baggage were no longer the controlling influences for writers who began their major work from the late 1960s onward.

Adrienne Rich was one of the great bridge figures in this generational transition. She was a critic of how capitalism functioned in daily life, particularly its impact on women, but she was not particularly interested in the rhetoric of socialism or its history. She was interested in how society worked for real people right now, and that preoccupation appears throughout this volume. It can be seen in an extract from her famous essay, included in the collection, called “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence”: The New Right’s messages to women have been, precisely, that we are the emotional and sexual property of men, and that the autonomy and equality of women threaten family, religion and state. The institutions by which women have traditionally been controlled—patriarchal motherhood, economic exploitation, the nuclear family, compulsory heterosexuality—are being strengthened by legislation, religious fiat, media imagery, and efforts at censorship. Rich excoriated what she saw as a “retreat into sameness”: an assimilationism that she regarded as “a renewed open season on difference.” The idea of difference came to her slowly as her life progressed from her days at Radcliffe through heterosexual marriage and widowhood, and to an eventual and extraordinarily fecund lesbian awakening. Her poetry collection A Change of World won the 1951 Yale Younger Poets prize. W. H. Auden, a judge for the prize, notoriously said that her poems were “neatly and modestly dressed, speak quietly but do not mumble, respect their elders but are not cowed by them, and do not tell fibs.” Notwithstanding the patronizing tone, this was a rare critical misfire for Auden, who seems to have missed something in Rich’s work that other critics have acclaimed. This collection is large enough to include all of “Compulsory Heterosexuality” and also a long chapter about Emily Dickinson called “Vesuvius at Home,” with a lengthy and perceptive analysis of the poet and her work. This chapter sets forth certain little-known facts, for example, that some of Dickinson’s poems about or to people existed in two forms, one with male and one with female pronouns. This is the detail-oriented, scholarly Rich who is so effective at supporting an argument. Unlike many of her contemporaries, Rich recognized the role of the poet as teller of unpleasant truths to society, and she saw poetry as a tool to accomplish this task. Unlike a poet like James Merrill or J. D. McClatchy, whose poetic focus was on the happenings of their own lives perched on a glass shelf slightly above the husk of society, Rich was all about writing to produce change. She pointed to the many forms of male power as exerted over women, everything from economic oppression and physical abuse to genital mutilation and denial of education. She found significant differences between lesbians and gay men, including divergent economic opportunities, very different approaches to sexuality, and a pronounced ageism among gay men. She was a lifelong critic of capitalism and specifically its impact on the arts, and worried that “an apparently disengaged poetics may also speak a political language—of self-enclosed complacency, passivity, opportunism, false neutrality.” A theme that runs throughout this collection is her dissatisfaction with feminists who don’t want to acknowledge the importance, or even the existence, of the lesbian experience in society. She notes that “feminist research and theory that contribute to lesbian invisibility or marginality are actually working against the liberation and empowerment of women as a group.” She considers lesbian existence to be a form of ordinary life and dislikes the term “lesbianism” as sounding clinical. Rather than an “ism,” it is simply an aspect of being female that many women experience. Rich declined President Clinton’s offer of the National Medal for the Arts in 1997, stating in her letter to the president that “art … means nothing if it simply decorates the dinner table of power that holds it hostage. The radical disparities of wealth and power in America are widening at a devastating rate. A president cannot meaningfully honor certain token artists while the people at large are so dishonored.” Among Rich’s heroes was Walt Whitman, whose wide-open vision of what America could be struck her as “vistas of possibility, not odes to empire.” That open horizon of possibility is what she wanted all women to have in their own right, not as adjuncts to men or even in opposition to men but without reference to the position of men. It is a sharply critical but ultimately positive vision for all of us.

Alan Contreras is a writer and higher education consultant who lives in Eugene, Oregon.