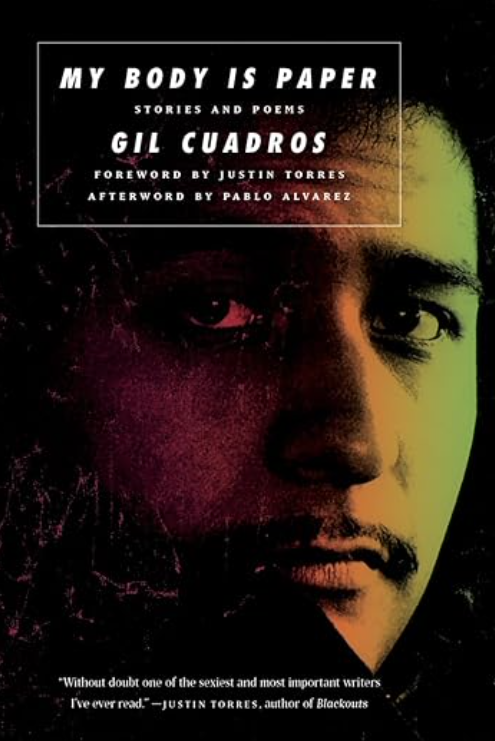

MY BODY IS PAPER

MY BODY IS PAPER

Stories and Poems

by Gil Cuadros

City Lights Publishers. 176 pages, $17.95

GIL CUADROS CEMENTED his reputation as a writer shortly before his death, at 34, with 1994’s City of God. This groundbreaking collection of short stories and poems explores being gay, Chicano, and living with AIDS in Los Angeles. Today, a growing interest in Cuadros’ writing has led to the discovery of previously unpublished prose and poems that touch on those same themes. His literary executor and a dedicated group of editors have compiled these pieces into an outstanding new collection, My Body Is Paper. Although long dormant, the work teems with life.

Men bond over shared interests (like gardening and architecture) and shared experiences (“our past loves and how they all died,” as detailed in the story “Need”). Survivors form relationships and nurse each other through health crises. In a time before gay marriage, they exchange rings to show their commitment. Current and past partners—Marcus and Kevin and Eric and Craig—merge into a composite person who symbolizes deep caring. When the narrator dreams of stepping naked and dripping from a healing bath in the unfinished novel or novella “Heroes,” a shape-shifting lover is there to greet him: “The towel floats invisibly, held by open arms.”

Men bond over shared interests (like gardening and architecture) and shared experiences (“our past loves and how they all died,” as detailed in the story “Need”). Survivors form relationships and nurse each other through health crises. In a time before gay marriage, they exchange rings to show their commitment. Current and past partners—Marcus and Kevin and Eric and Craig—merge into a composite person who symbolizes deep caring. When the narrator dreams of stepping naked and dripping from a healing bath in the unfinished novel or novella “Heroes,” a shape-shifting lover is there to greet him: “The towel floats invisibly, held by open arms.”

Several pieces address the experience of being multiracial. The parents in the story “Dis(coloration)” purposefully don’t teach their children Spanish to force them “to be as American as possible.” In the story “Hands,” the narrator, unable to communicate with a mother in her native tongue, fears disappointing her by being “like an Oreo, brown on the outside, white on the inside.” This heightened sense of otherness gives Cuadros’ narrators a unique vantage point from which to notice things about themselves, their partners, what people are like when they don’t know they’re being observed, and how they change when they realize they are. In “Heroes,” the narrator immediately regrets making his older lover Marcus feel self-conscious about the way he moves his hands while listening to disco music on his headphones, “as if I popped a delicate multicolored soap bubble floating in solitude across a park on a gentle wind.”

The good and loyal Marcus pops up in several places. We first see him striding through his nursery “in total command, like a god in his Eden” (“Hands”), then sitting on the floor drawing his lover in “Heroes,” his bent leg revealing a worrisome lesion. In the poem “Wedding Bands and Bone,” his skeletal hand falls through the hospital bed’s railing, and his ring slips to the floor. His lover, sitting bedside, is preoccupied with the ring when “A sudden breeze comes through the windows/ Sweeps my attention away, pulls him like leaves in a whirlwind/ till they are gone and all that’s left is stillness.” This is all so heartbreaking, but there’s no self-pity here. And because the writing is so direct, unadorned, and attuned to what’s happening in the moment, Marcus lives on—in these pages and afterward, in our minds.

The prose sometimes contains unexpected line breaks that suggest a sense of possibility, as if the experience Cuadros is writing about could have been rendered as a poem. Because My Body Is Paper contains undated work, it’s less about his evolution as a writer than about our experience of his deeply felt concerns: the pleasures and horrors of the body, the link between spirit and nature, the sense of meaning we can derive from carefully tended relationships. “We weren’t put down here for that,” the speaker’s mother insists in the poem “If She Could,” shaming her son for being gay, as if it were only about sex. While there is a lot of explicit sexual content in this collection, Cuadros’ trailblazing work shows us that being gay is so much more than that.

_______________________________________________________

Michael Quinn writes about books in a monthly column for the Brooklyn newspaper The Red Hook Star-Revue.