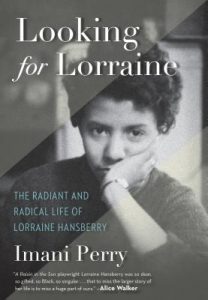

Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and

Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and

Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry

by Imani Perry

Beacon Press. 256 pages, $26.95

DOZENS OF WORKS of literary criticism and biographies for young readers (but not adults) have been written about playwright Lorraine Hansberry (1930–1965), author of the classic play A Raisin in the Sun (1959). Compressing her life, one in which her charisma, personal warmth, intellectual confidence, hard-hitting and often unpopular political and racial justice stances were much in evidence, must have been no easy task for Imani Perry, professor of African-American studies at Princeton.

Looking for Lorraine is a deeply felt biography in which Perry expresses her feelings of oneness with Hansberry through similarities in their backgrounds and reactions to political events. The book also offers critiques of many of Hansberry’s works, both published and unpublished. Its title was chosen as an homage to Isaac Julien’s 1989 film Looking for Langston. Langston Hughes’ poem “Harlem” contains the line that provided the title for A Raisin in the Sun: “What happens to a dream deferred?/ Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?/ … Or does it explode?”

The youngest of four, Lorraine Hansberry was born in Chicago in 1930 into a highly educated and well-to-do family. These attributes did nothing to insulate the family from violence and hatred, experiences that would appear in different forms in Hansberry’s plays and other writings. Hansberry was the first African-American in the women’s dorm at the University of Wisconsin-Madison when she started college as an applied arts major in 1948. Popular and quick to make friends, she took part in student productions. Her favorite play was Sean O’Casey’s Juno and the Paycock, which was set in the slums of Dublin. She found, as Perry notes, that it came from “a people for whom there was poetry in everyday expression.”

However, Hansberry was not interested in the academic life. She withdrew from school after two years and moved to Harlem, where she took an editorial and writing position at Freedom, a weekly newspaper published by Paul Robeson. She’d originally met Robeson, as well as Langston Hughes and W. E. B. Du Bois, when they visited her family during her childhood in Chicago. Her politics brought her to the attention of the FBI, and their surveillance began. But, writes Perry, “[t]hey would look for everything, and see very little.”

In 1953, she married editor and publisher Robert Nemiroff. Little is known of their private life, but he was a great support to her during their years together, even after their 1962 divorce. In Perry’s chapter “Sappho’s Poetry,” she delicately explores some of what is known about Hansberry’s same-sex relationships, though this is not the major focus of Looking for Lorraine. Perry analyzes Hansberry’s unpublished play “Flowers for the General,” about a lesbian love affair, “melodramatically composed and yet realistic,” so that it “could have easily been true.” As “L.H.N.” she wrote letters to the Daughters of Bilitis magazine The Ladder, and as “Emily Jones” she wrote short stories for both The Ladder and the Mattachine’s ONE magazine. Though Perry does not cite J. R. Roberts, it was Roberts’ annotated bibliography Black Lesbians (1981) that credited Ladder editor Barbara Grier with outing Hansberry in 1970 as the author of these letters and short stories.

In the late 1950s, Hansberry paid her first visit to Provincetown. One of her lovers, whom she probably met there, was photographer Molly Malone Cook (later the partner of poet Mary Oliver). It was in 1958 that she met James Baldwin, to whom she became “Sweet Lorraine,” and around the same time that she met Nina Simone, who said that when they got together, they never spoke of trivial matters. “It was always Marx, Lenin and revolution—real girls’ talk.”

Perry reproduces a list, both “mundane and profound,” that Hansberry made in 1960, of her likes and hates. “I like,” wrote Hansberry, “my homosexuality.” The list of likes includes ten entries about women and one about her husband. In her list of hates, “my homosexuality” is back, along with racism, death, pain, and the writings of Genet and Sartre.

Not surprisingly, Perry devotes a good deal of attention to Raisin in the Sun. It was the first play on Broadway by an African-American woman. Hansberry was the first black woman to win a Drama Critics’ Circle Award, in 1959. The show ran for 530 performances on Broadway, and its cast of luminaries included Sidney Poitier and Ruby Dee. Its success allowed Hansberry to buy a building in the Village. She rented an apartment to Dorothy Secules, a successful businesswoman with whom she was intimately involved.

Near the end of her life, she wrote in her journal: “When I get my health back I think I shall have to go into the South to find out what kind of revolutionary I am.” She was immersed in a number of writing projects almost to the moment of her death in 1965, at age 34, of metastatic pancreatic cancer. Her funeral, attended by over 700 people (including Malcolm X, just a few weeks before his assassination) was a star-studded event, featuring many of her friends from show business. Of the many honorary pallbearers, one was Dorothy Secules. There is so much more to learn about Hansberry: perhaps more will be revealed in Margaret B. Wilkerson’s Lorraine Hansberry: Am I a Revolutionary? whose publication is expected next year.

Martha E. Stone is the literary editor of this magazine.