The Stonewall Reader

The Stonewall Reader

Edited by the New York Public Library

Penguin Classics. 307 pages, $18.

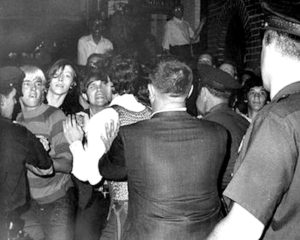

AT THE FIFTIETH anniversary of the Stonewall riots, we find ourselves with a plethora of books and memorial exhibits that document what Ed White calls “the fall of our gay Bastille.” The events of that last weekend in June 1969, when the police raided the little queer bar on Christopher Street, and the patrons, instead of meekly submitting, angrily fought back, inaugurated the “Year of the New Homosexual.” Things were never the same again. It was a “collective shriek heard round the world,” writes Larry Mitchell, one of the almost fifty contributors to The New York Public Library’s excellent anthology of witnesses.

Editor Jason Baumann, the library’s assistant director for collection development, has assembled a first-rate anthology of pieces that tell the story of the first decade of the Stonewall era. The first third of the book, “Before Stonewall,” offers a rich sampling of vignettes about the situation for gays and lesbians before the riots.

These were the days of life in the closet. We hear about secrecy, guilt, and furtive sex; about arrests, firings, and expulsions from the army; about “being thrown out of the house through a glass door”; about mental breakdowns and psychiatric “experts” who explained how homosexuals were “psychically retarded” and would end up committing suicide. All of these experiences thrust many homosexuals “into the gutter of self-contempt,” as activist Martha Shelley puts it.

Perhaps most damaging of all was the loneliness of the pre-Stonewall homosexual. Audre Lorde notes that this loneliness emerged from a sense that “there were not enough of us.” Some didn’t even know the word “gay.” Nevertheless, in the years leading up to Stonewall, there were efforts to create spaces where LGBT people could meet and socialize outside of the gay bars. Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon detail the 1955 formation of the Daughters of Bilitis, a club for lesbians. The curious name, they say, meant that “if anyone asked us, we could always say we belong to the poetry club.”

The homosexual, wrote Franklin Kameny in a letter to President John F. Kennedy, “is in much the same position as was the Negro about 1925.” Kameny, who was dismissed from his job as a government astronomer because of his homosexuality, excoriated the hostility, enmity, and animosity—“amounting to a state of war”—that the government directed toward gay and lesbian citizens. Society’s attitudes and policies were “Stone Age,” he said. Remarkably—and quite bravely—Kameny and a small band of other gays and lesbians picketed the White House for the right of American citizens to be different.

In the absence of social and legal reform, many pre-Stonewall LGBT folk carved out identities for themselves in defiance of the prevailing bigotry and stigmatization. Camp behavior and “other outrageousnesses,” Samuel Delaney recalls, was one such mode of defiance. It gave marginalized gay people the freedom “to say absolutely anything … except, of course, I am queer, and I like men sexually better than women.”

Books played a big role in pre-Stonewall lives, though the information they imparted was often stereotyped or inaccurate. “Much was made,” Barbara Gittings recalls, “of differentiating lesbians and male homosexuals into masculine and feminine types.” Even in most novels, she says, homosexuality “brought suffering or downright tragedy.” Craig Rodwell’s piece from The Gay Crusaders discusses the formation of the first gay bookstore, which he opened in 1967, an enterprise that met with harassment and threats.

The plight of transgender and non-binary people is also well documented in these pages. Christine Jorgensen recounts her sex-change operation and the media brouhaha that followed. Similarly, Virginia Prince, an early transgender activist, describes her journey toward self-acceptance. Mario Martino, who started the first counseling service for trans men in New York, recounts his ordeal with a series of “insensitive, cruel, and crude” lawyers when he sought to have his birth certificate reflect his gender identity.

In a 1966 interview for the journal The Ladder, Ernestine Eckstein, one of the few African-American lesbian activists at the time, declared that “homosexuals have to become visible and to assert themselves politically. Once homosexuals do this, society will start to give more.” Three years later, that call to action flared up at Stonewall.

The second part of the anthology gives us more than a dozen eyewitness accounts of the uprising. Needless to say, there are discrepancies among the various reports on some of the details, but all seem to agree, as Morty Manford put it, that “the festering wound of anger” was lanced that night. The crowd at Stonewall seemed to ask: “Why do we have to keep on constantly putting up with this?”

While the resisters were an eclectic bunch, activist and journalist Dick Leitsch confirms that drag queens and street kids—the so-called “nellies,” “swishes,” and “sissies”—“showed the most courage and sense during the action.” The eloquent historian Jonathan Ned Katz, in his Gay American History (1976), summed up the meaning of Stonewall this way: “We moved in a brief span of time from a sense that there was something radically wrong with us to the realization that there was something radically wrong with that society which had done its best to destroy us. … We experienced the present as history, ourselves as history makers.”

In the wake of the riots, the question soon became a matter of how to maintain the energy and focus. “What do we do to keep this going?” asked Miss Major Griffin-Gracy, a trans woman, in an interview. As we now know, the momentum did keep going.

The third part, “After Stonewall,” will impress any reader with how brave, emboldened, energetic, and passionate the first generation of post-Stonewall activists were. Writing in Come Out! Magazine, Perry Brass noted: “People in America stopped being bachelors or single Americans and started being gay women and men.” They let go of their fear and self-hatred, opting instead to make life “uneasy,” as activist Martha Shelley wrote, for straight society. Well-meaning heterosexual liberalism was no longer good enough.

The sheer number of organizations, events, community centers, newspapers, and movements that grew up in the immediate wake of Stonewall is impressive. Contributors to the anthology mention, among others, the Gay Liberation Front, Lavender Menace, Radical Faeries, Gay Lib Guerilla Theatre, STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries), and Salsa Soul Sisters. The early days of post-Stonewall action included calls for the rejection of exploitative institutions—bars, tearooms, baths—that promoted male supremacy and privilege.

By the late ’70s, performance artist Penny Arcade writes, assimilationist voices began to take over the gay liberation movement, policing the more fringe elements in the community. She complains about the “control freaks … who wanted to be accepted by the white middle class. They wanted to be officially Gay.”

As I made my way through the book, I kept wishing I’d had this volume when I was leading the GSA at the high school where I teach. The excerpts are superbly selected for solid information and impact. Very few are longer than ten pages, which makes them ideal for teaching. Baumann’s anthology gives us an almost agenda-free array of narratives and perspectives. The collective effect recaptures the effervescence, courage, and commitment of those first heady Stonewall-era years.