WHEN I LECTURE on Herman Melville, I’m usually asked whether he was gay. I answer, probably not. Then I’m asked if he ever had sex with men. I answer, probably, but only when he was young, and only while at sea. I then admit that Robert Aldrich’s compendium of LGBT biographies, Gay Lives (2012), has no separate entry for Melville. Aldrich claims that, while gay liberation mandates “an open and proud affirmation of sexual orientation,” he proposes that “sex does not provide the key to everyone’s life.” Apparently, sex alone is not enough. Aldrich argues that, because sex forms only a part of a person’s sense of his or her place in the world, sexual orientation should be a matter of “intimate affinities.” There are no personal confessions of such affinities about Melville. Whether Melville himself ever had such affinities is unknown, though he wrote of them.

The attempt to ascertain Mel-ville’s sexual orientation as an adult that is based on his writings has always proved challenging. One problem is that Melville did not write many books about his mature experiences. Another one is that, as a writer, he was not very good at plots. He never quite figured out what typically constituted a book but relied instead on other people (editors, publishers) to define what he was writing. Consequently, his first novel, Typee, was sold as a travel book on the exotic South Seas. It was actually packed with a great many things, like anti-imperialism and his personal issues with manhood. But these issues only muddied the waters. What interested Melville was the fabrication of an acceptable narrative that allowed him to discuss provocative topics like the nature of good and evil and how being a man means being in conflict with society.

Although Melville had famous ancestors, he had no models for the life that he sought for himself. In Billy Budd, he deleted a confession that fiction can only provide a brief “respite” from a world where the individual struggles with society. This conflict between personal ambition and fulfillment held Melville captive, because witnessing his father’s desperate efforts to strike it rich had taught him the futility of that kind of life. He had also seen the man he idolized die, raving (in Calvinist thought, such a death indicated that the father was damned forever) and bankrupt. The result was that while still a boy he had to enter the workforce at one of its lowest levels, as a seaman. There he learned what society does to men who fail, and how it builds empires on human suffering. Eventually, Melville realized that he had an affinity for those men who must make their way in the world without relying on class or even race. He learned that there was manhood elsewhere, and it was universal.

At sea, Melville found that he could fit in with a way of life that contradicted what on dry land he’d been taught was proper. This discovery extended into the sexual realm. Nevertheless, notwithstanding any notions that he may have picked up about sailors’ aggressive sexuality, his principal characters are often passive observers who rely on evasive words like “peep” or “glimpse” to report on same-sex activity. They experience no personal violence. Yet these narrators reflect the author’s difficulty with being fully responsible, both emotionally and sexually. It is why, in the novel Redburn, when the sailors force a spoiled boy to climb to the top of a mast by having a sailor bump his head against the reluctant climber’s backside, according to historian William Benemann (who has a piece in this issue), Melville’s wordplay relates an event that only “sails as near to the edge of homoerotic explicitness as he dares.” It is also why, when Redburn returns home, he makes sure to leave behind any evidence of his experience.

To those who don’t know about such things, the novel’s confusing tone may express only an adolescent’s fear of not fitting in. However, Melville’s language hints that “climbing the mast” means that a public sexual initiation is taking place. Such activity was at that time acceptable, even common practice among merchant seamen, but it was mainly confined to reciprocal masturbation performed chiefly below decks, and generally somewhat in private. This fact explains why later, when a shipmate worries that Redburn will shame the crew by not dancing well when they go on shore leave, the boy happily relieves “his anxiety on that head.” Melville implies here that the boy is willing to fit in with the seamen’s traditional social practices when on shore. Apparently, Redburn’s story is about the “green” beginners called “boys” who in popular sea chanteys prove to be both brave and sexually available.

Melville’s own life was so full of self-promotion that his relatives nicknamed him “Tawney” for the way in which he reworked his own part in the South Sea adventures that he wrote about. In these novels, he used the autobiographical “I” to suggest firsthand experience, which he expanded upon with exotic facts and erotic fantasies. In time, the family felt that life among the cannibals of the South Pacific had darkened Melville as surely as if he had returned home covered in pagan tattoos. These fabrications went into his first, and his only successful, novel Typee.

In Typee, young Tommo flees an onboard orgy of sailors and Polynesian women to go live among the people called Typee (“lovers of human flesh”), where he develops a strange leg injury. It allows him to be a pampered, passive guest while participating in strange sexual activities. Like a prodigal son, when Tommo discovers that the islanders are indeed cannibals, he runs back to civilization, only now he has fantastic stories to tell. Even today, Melville’s travel adventures still ring true because they reveal what men are capable of doing when transferred to strange places or living under unfamiliar circumstances.

Melville once wrote to his friend Richard Dana Jr., author of Two Years before the Mast, that no one could ever really begin to write about a man’s experience of the world without having gone through what they had endured at sea. In Redburn, Melville insists that “there are passages in the lives of all men, so out of keeping with the common tenor of their ways … that only He who made us can expound them.” A popular song of the times states this theme more plainly: “Well, you know what sailors are.”

Melville certainly did know, because he reveals, in the words of William Benemann, “a world that holds heterosexuality to be the norm, but which allows for a wide swath of sexual ambiguity.” In Billy Budd, for example, when the sailor spills greasy soup after a jolt during “sportful” talk below deck, Melville does not imply that Billy lacks masculinity from it. On the contrary, Melville encodes the understanding that mutual masturbation was respectably practiced at sea. He even has the ship’s police officer Claggart compliment the sailor on his “handsome” deed as the warship’s paragon. Similarly, in the chapter in Moby-Dick titled “A Squeeze of Hands,” Melville rhapsodizes on the menial task of squeezing sperm whale blubber: “Come; let us squeeze hands all round; nay, let us squeeze ourselves into each other; let us all squeeze ourselves universally into the very milk and sperm of kindness.” To the extent that the larger world was set up to sustain conflict between men, this easy ritual of mutual admiration could only confirm the general suspicion that sailors were inherently depraved. Established churches refused them entry, and everyone knew why.

Biographer Laurie Robertson-Lorant reminds us that, although Melville was born in Pearl Street in comfortable circumstances at the foot of Manhattan, he lived minutes away from the Five Points, a slum where respectable women could have witnessed workmen swimming naked in the river. Eventually, indoor baths were built to spare casual strollers from such “unexpected” rude sights, but because workers had to pay a fee to be decent indoors, nighttime bathing must have continued outside. Young Melville’s first glimpses of such men were probably nearby on the same “fiddler’s green,” where a strip of shore was restricted to sailors. It became a simple matter for him to transfer these Edenic Adams to the high seas.

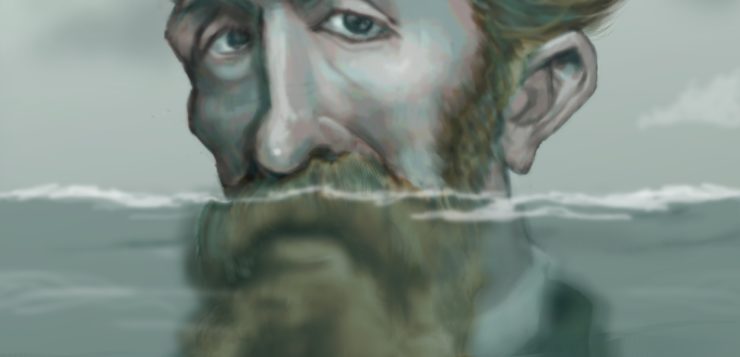

Throughout his work, Melville testifies to the beauty of men. He was himself strikingly good-looking, and he idolized his mentor Nathaniel Hawthorne, one of the handsomest men of his day. Billy Budd even contains a scene in which sailors of all the world’s races and colors pay homage to a “Handsome Sailor,” the nautical paragon of strength and beauty. In this case, he is a spectacular, free black man seen abroad in Liverpool, but the author goes on to extend the honor to include the equally savage and supposedly inarticulate blue-eyed, blond Billy Budd, who takes his place, according to Melville’s description of him, among the Anglo-Saxons, seen as an unconquered, barbarian race. As such, and as an illiterate orphan, Billy instinctively lashes out violently when the ship’s police officer Claggart slanders him. Yet, in this world at sea, the Handsome Sailor must die at the hands of white, imperialist brutal authority—hanged by the Royal Navy that has kidnapped Billy from a happy, natural life as a merchant marine aboard The Rights of Man. At the execution, Billy’s suspended corpse remains perfectly still, without displaying any of the involuntary spasms that are typical of a hanging—a demonstration of willpower that the sailors know raises him above the control of his accusers

As his last work, Billy Budd could be seen to stand for Melville’s last will and testament, except that the novel is unfinished, as Melville claimed that real life doesn’t fit neatly into an acceptable plotline. It may be that he could only dive so far into the depths of his desires and no further, his secret being that he could not entertain other possibilities for his own manhood.

Class and race also constricted him, and he was aware of his place in American history as a white man, especially because of his Revolutionary War ancestry. In his own experience at sea with people of all races, he had learned that he would always be the white man with an “acceptable” ancestry. But because of his travels as a white man abroad among others races held captive by white imperialism, he had learned that he could ask: “Who ain’t a slave?” So, Melville accepted that what he had learned elsewhere could not sustain both his leveling experience abroad and his racist life at home. He had learned that a man cannot escape his initial instructions in society, which bind him forever.

Nevertheless, because Melville had lived another life but accepted the idea of a traditional home, he felt conflicted and neglected his home life and duties. He was a difficult husband and a failed father, one of whose sons committed suicide. That’s why, in Billy Budd, he gives the last words to the failed father figure Captain Vere and to the men who were Billy’s companions. He has Vere repeat Billy Budd’s name in a regretful deathbed rant, and the seamen commemorate the Handsome Sailor’s remarkable resistance to imperialist white authority in a ballad. The authorities also commemorate Billy’s exceptional demonstration of autonomy by contributing a misleading account of the sacrificed man. Consequently, Billy’s story cannot be contained by one point of view.

In his own life, Melville failed to establish the “intimate affinities” that today would be assumed to define a gay life. For example, in a passionate letter of gratitude to Nathaniel Hawthorne for his kind words about Moby-Dick, Melville wrote: “The divine magnet is on you, and my magnet responds. Which is the biggest? A foolish question: they are One.” Hawthorne did not respond to this barely disguised fantasy. He probably chalked it up to a friendly, infatuated fan’s desperate recourse to the sentimentality that was permitted between men at that time. What was needed, but apparently impossible in those times, was a simple, direct statement of love to a close friend, but Melville’s experience of sexuality at sea confused him.

References

Aldrich, Robert. Gay Lives. Thames and Hudson, 2012.

Benemann, William. Male-Male Intimacy in Early America: Beyond Romantic Friendships. Harrington Park Press, 2006.

Redfern, W. D. “Between the Lines of Billy Budd.” Journal of American Studies, v. 17, no. 2. December 1983.

Robertson-Lorant, Laurie. Melville. A Biography. Clarkson Potter, 1996.

Rolando Jorif is an assistant professor of English at CUNY–Borough of Manhattan Community College.

Discussion1 Comment

One might want to look at the examine the love that Melville had for Nathanial Hawthorne. For example, on the website themarginailian as well as doing a search in Google for “Herman Melville and Nathanial Hawthorne.