A UNION LIKE OURS

A UNION LIKE OURS

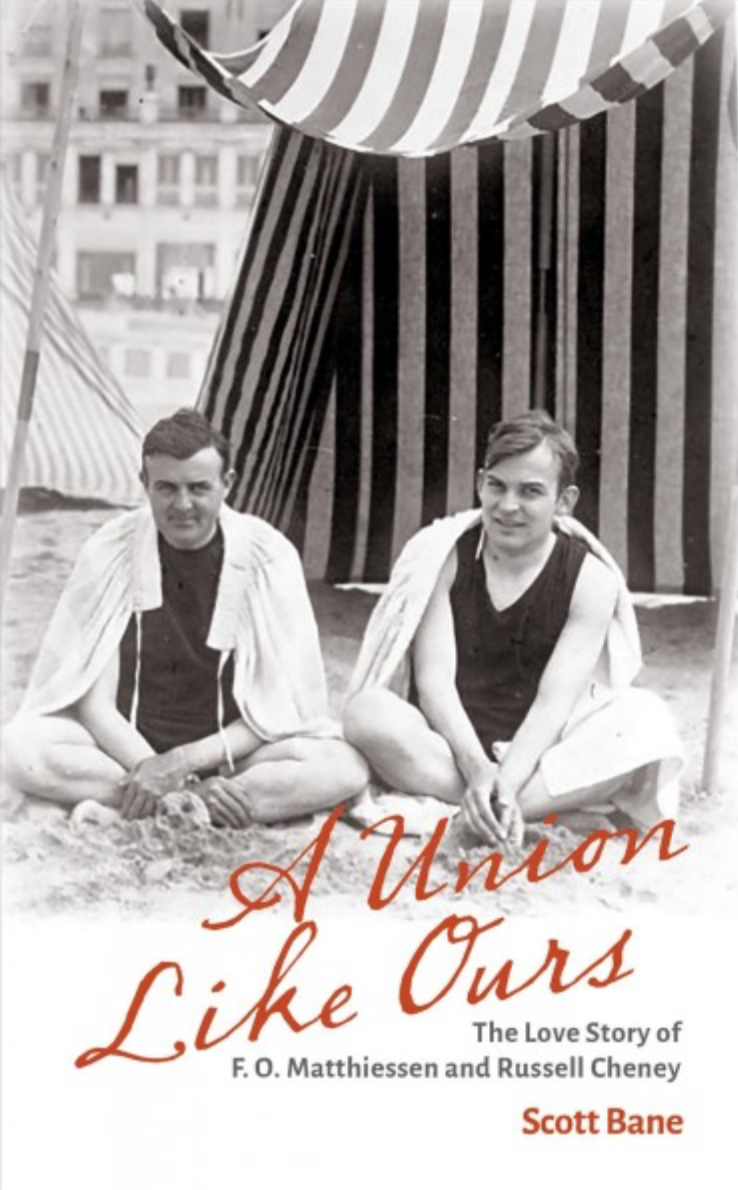

The Love Story of F. O. Matthiessen and Russell Cheney

by Scott Bane

Univ. of Massachusetts Press

302 pages, $24.95

BOTH RUSSELL CHENEY, the visual artist, and F. O. Matthiessen, the Harvard professor who founded the field that we now call American Studies, came from wealthy families. The Cheneys owned an entire town in Connecticut, South Manchester, where they housed the people who worked in their silk manufacturing factory, a business that did millions of dollars every year until the Depression and the rise of artificial fabrics. Matthiessen’s father owned Westclox, the clock manufacturer, not to mention thousands of acres in California that he eventually developed. Both men went to Yale, where each was admitted into the senior society Skull & Bones. Though there was a 21-year age difference between them—Cheney was born in 1881, Matthiessen in 1902—they both belonged to the same America, really, one in which colleges like Yale and Harvard educated young Protestant males from “good” families with inherited wealth.

Now all that’s changed. If you were to walk across Harvard Yard today between classes, you’d see a student body that looks more, as the saying goes, like America—though Asian-American parents have accused the university of using an admission process that discriminates against Asians in a lawsuit that’s currently being argued before the Supreme Court. But in the 1920s, Harvard and Yale were still associated with what we now call privilege. Matthiessen, who was raised by his mother after his parents’ divorce, grew up in Tarrytown, New York, where he was enrolled at the Hackley School. At that time he would go into Manhattan to hook up with men he picked up in theaters, public washrooms, and parks. Psychiatrists would later attribute Matthiessen’s attraction to older men to his lack of a father figure, and perhaps that was a factor when, still in college, he met Russell Cheney on a ship coming back from Europe.

It was love at first sight—on Matthiessen’s part at least.

Andrew Holleran is the author of the new novel The Kingdom of Sand.