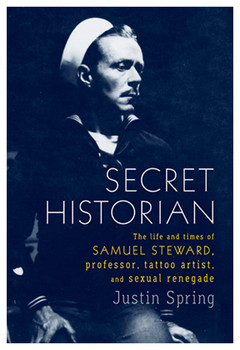

Secret Historian: The Life and Times of Samuel Steward,Professor, Tattoo Artist, and Sexual Renegade

Secret Historian: The Life and Times of Samuel Steward,Professor, Tattoo Artist, and Sexual Renegade by Justin Spring

Farrar Straus & Giroux. 490 pages, $32.50

IN SECRET HISTORIAN, Justin Spring offers a compelling, well-written account of Samuel Steward’s many lives as an accomplished professor and teacher, a respected novelist writing as Phil Andros, and a skilled tattoo artist and pornographer. Steward knew many of the noted artists and personalities of his era—André Gide, Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas, Thornton Wilder, Thomas Mann, George Platt Lynes, and Alfred Kinsey, among others—but Steward himself has remained a footnote in the cultural and sexual history of the mid-20th century.

Born in 1909 in Woodsfield, Ohio, Steward’s mother died suddenly when he was only six, and his father’s alcohol and drug addictions made it difficult for him to raise a son alone. Steward was sent to live with his devout Methodist aunts who ran a boardinghouse in town, and who instilled the fear that even the “slightest brushing of my hand against my penis” would lead to a host of physical abnormalities. He was a voracious reader and in his early teens found a copy of Havelock Ellis’s Studies in Psychology of Sex, Volume II: Sexual Inversion, left behind by a guest, under one of the boardinghouse beds. Later, Steward would recall “not only did I discover that I was not insane or alone in a world of heteros—but I [also]learned many new things to do.” The book gave the young Steward a way of understanding his sexual desires without any of the Methodist morality. It also brought together his love of writing with sexual experimentation that he would pursue for the rest of his life.

In detailing the complexities of Steward’s life, Secret Historian is anchored in his sexual experiences. While reading the book, I was reminded of Janet Malcolm’s claims that a biography is a “collusion” between reader and the writer in which we both get to “stand in front of the bedroom door and try to peep through the keyhole.” Spring doesn’t just allow us to peep through the lock, he picks his way through it, and leads us into hotel rooms, apartments, tattoo parlors, and even elevators, detailing the range of Steward’s sexual life. But if there is collusion in this story, it’s a three-way affair that includes Steward himself, who kept both a detailed journal of his sexual encounters and a “Stud File” card catalog of the men he had sex with, which ultimately totaled nearly 800 cards.

The file includes both the famous and the anonymous. Among the famous was Rodolfo Guglielmo, i.e., Valentino, who was traveling to Chicago incognito when he stopped in Columbus, Ohio. Steward, an eager undergraduate, arrived at his hotel room seeking an autograph and left with a new entry in his sex journal and a memento of Valentino’s pubic hair, which, Spring writes, he “kept in a monstrance at his bedside until the end of his life.” In his “Stud File,” on the card marked “Guglielmo,” Steward wrote simply: “Nuf sed.”

On a trip to Europe in 1937, by then a professor and published novelist, Steward arranged a meeting with the aging Lord Alfred Douglas. Douglas, then in his sixties, had since renounced his “sodomite” ways, converted to Catholicism, and married (way back in 1902). But Steward was determined, and while the idea of going “to bed with him was hardly the most attractive prospect in the world,” he rationalized it as the only way to link himself to Oscar Wilde. Their meeting, at first cordial and polite, turned in a different direction once Douglas opened a bottle of gin: “Within an hour and a half we were in bed, the Church renounced, conscience vanquished, inhibitions overcome, revulsion conquered, pledges and vows and British laws all forgotten. Head down, my lips where Oscar’s had been, I knew that I had won.”

As you get deeper into the book, the sexual experiences become more expansive, including sex parties, S/M, and sex for pay. As Spring suggests, for Steward there was a fine line between the thrill of sexual encounters and the business of turning these experiences into journal entries or fictional stories. “Through these collections of facts, figures, and objects,” writes Spring, “Steward was able to put the experiences into order, consider their relative importance (or unimportance), and, essentially, to daydream about his own risk taking sexual activities with a sense of both detachment and control.”

As you get deeper into the book, the sexual experiences become more expansive, including sex parties, S/M, and sex for pay. As Spring suggests, for Steward there was a fine line between the thrill of sexual encounters and the business of turning these experiences into journal entries or fictional stories. “Through these collections of facts, figures, and objects,” writes Spring, “Steward was able to put the experiences into order, consider their relative importance (or unimportance), and, essentially, to daydream about his own risk taking sexual activities with a sense of both detachment and control.”

Throughout the 1940’s, Steward maintained a complicated routine of building his career as a respected (and closeted) professor and novelist, and pursuing his increasing desire for more daring sexual adventures. In the early 50’s, he learned the skill of tattooing that would eventually satisfy both his artistic interests (he had for years been painting and drawing) and his desire to meet military and working-class men. In his journal he wrote: “The sight of one or more [tattoos]on an arm becomes terrifyingly attractive; I find myself wanting to lick the tattoo, or suck it—or at the very least grab it and run my finger over it.” While still giving lectures and attending faculty meetings at DePaul University, Steward worked weekends at his tattoo shop in downtown Chicago under the pseudonym Phil Sparrow. When word of his business reached the deans at DePaul University, Steward was fired, though the dismissal was also a relief, “for he knew there was really no place for him in that world.”

It was also in the early 50’s that he met Alfred Kinsey. Steward would become a rich subject for Kinsey’s continuing research, submitting yearly journals of his sexual adventures and performing in a number of films. As Spring notes, the first film Kinsey ever made of sexual activity was of Steward playing the submissive in an S/M encounter, filmed in his Chicago apartment. Steward himself had been using an early Polaroid camera to photograph his sex parties, both as an extension of his sexual archiving and as tokens to give and send (in violation of the postal laws) to friends along with fictional, erotic stories based on his encounters. Spring details the exchange of such stories in a chapter on photographer George Platt Lynes, who encouraged Steward’s early erotic fiction.

Over the next decades, Steward dedicated himself to tattooing and writing homoerotic stories for small magazines, such as Der Kries, and published with small presses in Europe and the U.S. He wrote two mainstream, nonfiction books on the history of tattoo art, and edited a collection of his letters from Gertrude Stein. He also wrote personal recollections in the 70’s and 80’s for The Advocate that were often open and direct. One in particular was an essay about his sexual liaisons with writer Thornton Wilder, who encouraged Steward’s writing in the 1930’s. Detailing specific dates, places, and sexual activities (taken from the “Stud File”), the essay was a response to Gilbert Harrison’s forthcoming biography of Wilder, in which all mention of the writer’s homosexuality was left out. The essay was an early entry into the debates about the nature of literary outings, the echoes of which are still heard today.

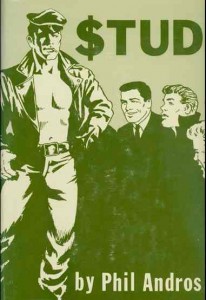

Steward is best remembered for his Phil Andros novels (Phil Andros is how Steward is currently listed in Wikipedia). These novels allowed Steward to turn his own experiences into the character of a rough, masculine sexual adventurer. They were ultimately the “fiction that gave [Steward’s] life meaning,” writes Spring. Published by small presses in the pulp genre, they had a significance to gay readers of the 60’s and 70’s, offering a “validation of the pleasures of homosexual sex,” in the words of John Preston, whose own writings were influenced by Steward.

Steward is best remembered for his Phil Andros novels (Phil Andros is how Steward is currently listed in Wikipedia). These novels allowed Steward to turn his own experiences into the character of a rough, masculine sexual adventurer. They were ultimately the “fiction that gave [Steward’s] life meaning,” writes Spring. Published by small presses in the pulp genre, they had a significance to gay readers of the 60’s and 70’s, offering a “validation of the pleasures of homosexual sex,” in the words of John Preston, whose own writings were influenced by Steward.

In telling the complex story of Steward, Spring refrains from making easy cause-and-effect narratives about the darker sides of the writer’s experiences: his alcohol and drug addictions, his attempted suicide, or his embrace of dangerously violent sex. In the end, what was most significant in Steward’s life and work was an effort, as Spring argues, “to demystify homosexual erotic activity and at the same time to present it in all its physical and emotional complexity.” His commitment to this work effectively marginalized him from an academic career and mainstream publishing. His place in the history of sexuality has been a marginal one as well, and Spring’s biography rightfully corrects that. Today, when the conventions of marriage anchor our public discussions of gay and lesbian experience, Secret Historian reminds us of the complexities of our past, and the problems of holding too tightly to any one sexual norm.

James Polchin teaches writing at NYU and is a frequent contributor to these pages. He also writes and edits the blog writinginpublic.com.