IF YOU WERE to ask a teenage boy what he thought of a movie that was nearly devoid of women characters and was instead filled with muscular, handsome men who are often physical with each other and sometimes scantily dressed, you would probably get an answer that included the word “gay,” in both teenage senses of the word (homosexual and bad). And yet, that same young man might well be part of the huge audience of young men who flock to the action movies that feature just this sort of scenario.

Modern action films have their roots in that most macho of genres, the Western. Classic Westerns featured morally righteous heroes defeating evil men and action sequences like shootouts, showdowns, stunts on horses, and old-fashioned fist fights. The next evolutionary step in the action genre was the rise of the maverick cop film, with movies like Bullitt (1968) and The French Connection (1971) emerging in the late ’60s and early ’70s. The maverick cop genre was essentially an update of the Western in which the action was moved from the Old West to contemporary urban areas, and horse stunts were replaced with car chases, but the gritty violence and the theme of good and evil remained intact. A third major step happened in the early 1970s with the rise of martial art films like Enter the Dragon (1973) and The Big Boss (1971). These films focused more on hand-to-hand combat than on gun battles or chase scenes.

Then came the ’80s, and a new style of action movie started to make its way to American theaters. These films were hybrids, taking elements from the earlier genres. They featured the same tropes of gun fights and stunts. The heroes were men who worked within an authoritative institution such as the police or the military, but they were outsiders who opposed the establishment and focused on their own sense of morality. Another feature of these movies was more hand-to-hand combat, as in the many martial arts films of this era. But what was really new and different about these movies was that they starred men with chiseled bodies who usually shed more and more clothing as the film went on. And they starred actors, such as Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger, who were not chosen for their acting skills but for their macho physique.

Throughout this history, the heroes have always been men who were ostensibly straight, indeed masculine to a fault. And yet, for just as long, these action films have flirted with gay subtexts. Even the most macho films have often included allusions to gay culture, and some of them have even featured gay characters. As action movies continued to progress from the 1980s, the subtext has evolved as well, so that homosexuality has moved from subtle hints to obvious metaphors and even outright eroticism. What follows are several examples that I hope will demonstrate this historical sequence.

Ben-Hur (1959)

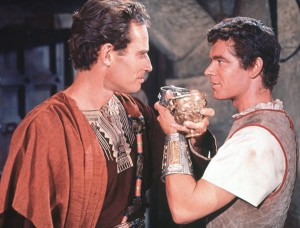

The film takes place in 26 AD as a Jewish prince and merchant named Ben-Hur returns to Jerusalem after years away. Shortly after returning, he gets on the wrong side of the commander of the Roman guard, who is his childhood friend Messala (Stephen Boyd). An accident at Ben-Hur’s home becomes an excuse for Messala to arrest Ben-Hur and to condemn his former friend to three years as a galley slave. By punishing Ben-Hur in this way, Messala hopes to intimidate the Jewish community and dissuade it from rebelling against the Romans. After being released from his sentence, Ben-Hur vows to get revenge on his former friend and goes on to high adventure in this pursuit. In the 1996 documentary The Celluloid Closet, Gore Vidal, who was one of four uncredited screenwriters, said that he didn’t think that Messala had a good enough reason to condemn his old friend to such a horrible fate. After all, if Messala just wanted to intimidate the Jewish community, why not arrest a prominent Jewish person with whom he had no relationship? While Ben-Hur and Messala did have a disagreement over quashing Jewish rebellions, Messala’s reaction is completely over the top. The problem is that Ben-Hur’s punishment is the linchpin of the three-hour film. Looking to remedy this problem, Vidal said that he discussed with director William Wyler an idea that would make Messala’s actions a bit more understandable. Vidal suggested that Ben-Hur and Messala had been former lovers as teenagers. When Ben-Hur returned to Jerusalem, Messala wanted to continue the affair, but Ben-Hur did not. Stung by his former lover’s rejection, Messala condemned his friend to three years as a galley slave. There’s one scene that Vidal points to as proof of the relationship. It comes when Messala and Ben-Hur see each other for the first time after the latter’s return. They hug tightly, and when they pull away, Messala stares deeply into Ben-Hur’s eyes. Then they play a game in which spears are thrown at a target, and they remark on each other’s virility. Finally, they talk about how close they use to be while clasping each other’s forearms and looking into each other’s eyes. The scene closes with Messala and Ben-Hur intertwining arms and drinking wine, again with eyes locked. According to Vidal, only Boyd knew about the past relationship between the two characters, and Heston wasn’t told about it. This actually would have helped with the direction of the scene, because when Messala looks at Ben-Hur, there’s a sense of longing that he discloses with his come-hither eyes. But as Ben-Hur stares back, he doesn’t return the longing gaze, because he has moved on. Heston vehemently denied that Messala and Ben-Hur were lovers and claimed that Vidal barely worked on the script. Both Boyd and Wyler died before Vidal went public with his version, so we will probably never know for sure. The Wild Bunch (1969) Often cited as one of the most violent Westerns of all time, Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch is about a group of aging outlaws led by a man named Pike (William Holden). They are looking for one last heist before they retire. A major obstacle in their path is Pike’s former partner Deke, who’s leading a posse of bounty hunters in pursuit of the gang. Despite the movie’s intense violence, the story also has a tender gay subtext. For starters, it is after all a group of single men living away from society in a place that’s completely devoid of women. Famed film critic and theorist Stephen Prince characterized their life together as a “gay utopia.” Then there’s the relationship between Pike and one of the gang members, Dutch (Ernest Borgnine). They seem to have a deeply intimate relationship that goes beyond mere friendship. At night, they sleep away from the other men, and the two have hushed conversations together. Another clue is that when Dutch is dying, he keeps repeating the same word over and over again until he expires: “Pike, Pike…” The evidence is right in plain view. For starters, the navy suits are tight-fitting to show off the muscular bulges of the actors. Then there are the more overt scenes, such as one in the locker room in which all the men are wet, wearing only towels, and their stares linger for an awfully long time. Finally, there’s the volleyball scene in which Maverick and “Iceman” (Val Kilmer) play shirtless volleyball. The game, which does not move the plot along at all, is a montage of hot, sweaty guys volleying away, and there are plenty of man-on-man embraces while “Playing with the Boys” by Kenny Loggins plays in the background. Quentin Tarantino has a theory about all this: he suggests that Top Gun is actually about Maverick’s struggle with his sexual identity. According to Tarantino, the female love interest in the film, played by Kelly McGillis, represents heterosexuality, and the flight school represents the gay lifestyle. For a while, Maverick tries to do both, but then Goose dies and Maverick mourns him as if he’d lost his lover. He now knows the pain of losing someone he really cares about and considers leaving the lifestyle for something “safer.” But in the end he has overcome his sadness about losing Goose, and he flies together with Iceman and the rest of the men, finally joining the community. As the film ends, Maverick and Iceman are victorious. After a hug, Iceman tells Maverick that he can fly with him any time. Tango & Cash (1989) That brings us to Andrey Konchalovsky’s Tango & Cash, starring iconic action stars Sylvester Stallone and Kurt Russell. On the surface, Tango & Cash is a typical buddy cop movie. Where it differs is in the strong gay theme that runs through the entire film. Tango (Stallone) is a meticulous and fashionable guy who’s forced to team with Cash (Russell), a slob who often looks like he might be working undercover as a drug addict. Tango is also uptight and repressed, while Cash is free and easy. Cash even wears a dress at one point. The gay subtext also weaves its way through the storyline. After Tango and Cash are framed for a crime, they’re arrested and put in prison, where they converse freely, joke around, and even, while naked in the prison shower, try to grab each other’s junk. In a later scene, Tango comments upon the size of Cash’s manhood, calling him the “Elephant Man.” Also, as in many buddy cop movies, there’s a female love interest for at least one of the cops—in this case Cash, and the love interest happens to be Tango’s sister, who physically resembles her brother. Even though Cash pursues Tango’s sister throughout the movie, Tango & Cash ends on a rather queer note. Before the credits roll, there’s a short scene of Tango and Cash cheering and celebrating. Their arms are raised above Tango’s sister’s head, and the two men are holding hands with their fingers interlocked. X-Men: First Class (2011) For their entire publication history, the X-Men comics have included representations of minority groups. The X-Men are a group of outsiders who are different simply because they were born that way, and they are both shunned and feared because of it. In 2004, the X-Men comics started to focus on issues that the LGBT community were dealing with, starting with the Joss Whedon story arc called The Astonishing X-Men. This narrative was driven by the introduction of a “mutant cure” that would make people with mutations “normal.” The series came to the big screen in 2000, when Bryan Singer, an openly gay man, took on directing duties for the movie franchise. Singer wanted the X-Men to represent the struggles of the gay community. By the time the series got to X-Men: First Class, directed by Matthew Vaughn—the only X-Men movie that was not directed by Singer—the film’s gay context was fairly well-established. There are sly lines that tip us off, such as Beast’s reply when asked about his status as a mutant: “You didn’t ask, so I didn’t tell.” At the heart of the story, there’s a strongly implied gay relationship between Charles “Professor X” Xavier (James McAvoy) and Erik “Magneto” Lehnsherr (Michael Fassbender). Both are mutants, but they have drastically different views of the world. Magneto is downbeat, having lost people who were close to him because of his powers. As an adult, he is angry at a world that shuns him for being different. Professor X doesn’t share Magneto’s bleak outlook and believes that one day non-mutants and mutants will live in harmony. Despite their polarized outlooks, the two become close as they track down other mutants to join their group. During that time, the two become intensely intimate. In one scene, they share a powerful mind connection that leaves them both in tears; in another, they even share a bed. While it’s not stated outright, the film strongly hints that the two men are lovers. Of course, suggesting the movies may have gay subtext and that Magneto and Professor X were lovers didn’t sit well with some viewers, who took to the social media to debate it. That’s when the subtext was addressed by one of the screenwriters of X-Men: First Class, Zack Stentz. In a posting on Facebook, Stentz stated that the X-Men are an allegory for the LGBT community. He also said that the symbolism helped draw both Singer and Ian McKellen to the franchise. What’s so interesting about the success of 300 is how overtly homoerotic the film is. There’s plenty of screen time devoted to the actors’ bodies, and the film is an homage to the beauty of the male figure. But 300 goes further than that in presenting non-mainstream sexuality. For example, director Zach Snyder purposely made the film’s antagonist, Xerxes (Rodrigo Santor), eight feet tall, androgynous, and pansexual because, he commented: “What’s more scary to a twenty-year-old boy than a giant god-king who wants to have his way with you?” That 300 was targeted directly at young men—and that it grossed $450 million worldwide, and that it spawned a sequel in 2014 with even more muscular men—is a fact that was surely not lost on the studios. Stay tuned! Robert Grimminck is a Canadian crime-fiction writer and a contributor to the on-line site listverse.com. The 1950s was definitely not the best time for screenwriters to openly include gay characters or storylines in a film, but that doesn’t mean they weren’t secretly used. A perfect example of this hidden subtext is William Wyler’s Ben-Hur, which stars Charlton Heston in the title role.

The 1950s was definitely not the best time for screenwriters to openly include gay characters or storylines in a film, but that doesn’t mean they weren’t secretly used. A perfect example of this hidden subtext is William Wyler’s Ben-Hur, which stars Charlton Heston in the title role.

Top Gun (1986) Tony Scott’s Top Gun follows Pete “Maverick” Mitch (Tom Cruise), a talented fighter pilot who has a problem with authority. Maverick, along with his radar intercept officer “Goose,” are given a chance to train with the Navy’s prestigious Fighter Weapons School. The story revolves around Maverick’s struggles with the lockstep uniformity of the Navy, and the film climaxes with some impressive dogfight scenes while upbeat Kenny Loggins songs play in the background. What’s interesting is the direction the filmmakers took with Top Gun: there’s a thinly veiled homoerotic feel to what should be a very macho movie.

Tony Scott’s Top Gun follows Pete “Maverick” Mitch (Tom Cruise), a talented fighter pilot who has a problem with authority. Maverick, along with his radar intercept officer “Goose,” are given a chance to train with the Navy’s prestigious Fighter Weapons School. The story revolves around Maverick’s struggles with the lockstep uniformity of the Navy, and the film climaxes with some impressive dogfight scenes while upbeat Kenny Loggins songs play in the background. What’s interesting is the direction the filmmakers took with Top Gun: there’s a thinly veiled homoerotic feel to what should be a very macho movie. Buddy cop movies are a staple of the action genre, and they usually follow a standard format. Two unlikely cops are put together as partners, which leads to comedic clashes and misunderstandings as they work toward some goal. By the end, they’re a harmonious couple working in tandem, and their differences now complement each other. (This type of storyline is also the basic format of screwball comedies of the 1930s and ’40s, such as It Happened One Night and The Philadelphia Story, which were what film critic Andrew Sarris called “sex comedies without sex.”)

Buddy cop movies are a staple of the action genre, and they usually follow a standard format. Two unlikely cops are put together as partners, which leads to comedic clashes and misunderstandings as they work toward some goal. By the end, they’re a harmonious couple working in tandem, and their differences now complement each other. (This type of storyline is also the basic format of screwball comedies of the 1930s and ’40s, such as It Happened One Night and The Philadelphia Story, which were what film critic Andrew Sarris called “sex comedies without sex.”)

300 (2006) When Zack Snyder’s 300 was released in March 2006, expectations for the film’s success were not very high. The story of the 300 Spartan warriors holding off 300,000 Persian soldiers in the legendary Battle of Thermopylae was shot on a sound stage in front of green screens, it didn’t have any big movie stars, and it was panned by critics. But in its opening weekend, it made $70 million, and it kept going strong for many weeks. The reason for the success was that young men came out in droves to see the sword-and-sandal epic that had a cast of absurdly muscular men wearing loincloths and capes as they pierced their foes with swords and spears.

When Zack Snyder’s 300 was released in March 2006, expectations for the film’s success were not very high. The story of the 300 Spartan warriors holding off 300,000 Persian soldiers in the legendary Battle of Thermopylae was shot on a sound stage in front of green screens, it didn’t have any big movie stars, and it was panned by critics. But in its opening weekend, it made $70 million, and it kept going strong for many weeks. The reason for the success was that young men came out in droves to see the sword-and-sandal epic that had a cast of absurdly muscular men wearing loincloths and capes as they pierced their foes with swords and spears.